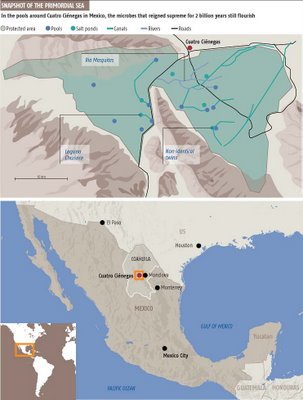

[Image: The present tectonic structure of North America, mapped by Ron Blakey, Professor of Geology, Northern Arizona University].

While out in California last month, hiking through Death Valley – on a cloudy day it looked like a painting by Caspar David Friedrich: an earth of snow, not salt flats – I read that California is actually a welded-together mass of remnant archipelagos and former island arcs.

In other words, down there in the Californian gravel are the buried edges of old island chains – and the whole state is still shivering with collision, making adjustments, popping loose and sticking, always on the move… then stopping.

Much is made of the apparent poetry of driving over the San Andreas Fault, which divides California into a left-half and a right-half, a coastal zone and a continental shield; but what of the silent lines you walk across everyday, from one former island to the next, unaware that those lands had even once been separated?

Midway through the trip, I picked up a copy of John McPhee’s Assembling California, in which he describes residual structures of ancient geology with “no known bottom” because they cut so deep. He talks about “the metamorphosed remains of what had once been an island arc,” and how, through constant collision and restlessness, entire “Newfoundlands, Madagascars, New Zealands, Sumatras, [and] Japans” have all jostled together, ramming one into the other, year after year, piling up, forming “the outermost laminations of new landscapes.”

This is “the docking of arc and continent,” a mismatched mess of rock “now consolidated as California.”

“California,” then, is just the temporary shape taken by these lost islands and unknotted seafloors.

Of course, then I found these unbelievable maps by Ron Blakey last week and I almost passed out. Utterly ingenious, each map represents “the paleogeography of North America over the last 550 million years of geologic history.” You can actually watch as California comes home to collide.

[Image: The southwestern coastal archipelagos of North America, 310 million years ago; map by Ron Blakey].

But let’s pull back and start 420 million years ago (bypassing some 130 million years’ worth of Blakey’s maps).

This is North America, a tropical archipelago, covered in surreal vegetation, blowing seeds across itself – Shelley’s “thousand nameless plants sown by the wandering winds” – cross-pollinating, hybridizing, surrounded by shallow seas, chugging northward over the equator.

75 million years later (below), what will eventually be North America has broken into pieces, partially flooded, surrounded by clusters of islands. These scattered subcontinents are about to collide with the north by northwestern edge of Africa – and unbelievable arcs, inlets, atolls, and bays all stretch across the landscape.

What was it like to live in that geography? What sounds did the forests make? What did the stars look like? What half-legged fish swam through those waters?

Another 50 million years pass, and the collision with Africa is well underway. Deserts are forming in the American southwest. Global wind patterns shift due to the distribution of landmasses.

Weird species that only live for a million years, and leave no fossil record, run unimpeded across giant landscapes of exposed bedrock.

Then the Atlantic rift begins; the Appalachian Mountains, which passed through Morocco, are now split onto three continents: North America, north Africa, and the embryonic British Isles, which drift northward, cultivating Albionic energy in ancestral swells of warm sea. William Blake will be born there – and Shelley, who’ll write of a time “when St. Paul’s and Westminster Abbey shall stand, shapeless and nameless ruins, in the midst of an unpeopled marsh.”

150 million years ago. California is already starting to form: it’s a distant horizon of islands in the Pacific. Those mountains of rock above water are coming in toward the mainland, slowly, lurching forward on broken faults, a conveyor belt moving masses east to raise hills in a ring around Los Angeles, propelling the Sierra Nevadas upward, walling-in the great Arizonan desert now temporarily beneath the sea.

Could you map today’s California according to the island chains it used to be?

And look at Mexico: it’s a weird spit of land, hooked and crooked through the oceans, collecting islands onto itself. What would it have been like, walking through those coastal mountains? And if you carved an entire island to look like the cathedral of Notre-Dame, what would it look like, breaking waves, coming toward you over ten million years, eventually colliding with the cliffs you stand on?

What’s amazing in the above two images is that, in only 40 million years, an entire system of archipelagos has rammed into the mainland, assembling what will eventually become known as California, tipping the Rockies, torquing belts of metal into metamorphosed ribbons today exposed by roadcuts.

What must that time period have been like? With thousands of small islands – a whole Indonesia – off the coast, groaning at night with tectonic pressure, shattering from strain, causing landslides, you could have boated from bay to bay, mapping species, collecting rocks – knowing that beneath your feet is what will someday be Bakersfield, Santa Barbara, Death Valley.

But now, in the map below, look at Mexico again: it’s a broken ridge of almost-islands, cooking in the Cretaceous sun. The Yucatan is an island. The whole Pacific coast is a weather-beaten cliff of caves and pockets.

This was 65 million years ago.

Now the North American inland sea has sealed up, and a riverine bay several orders of magnitude larger than the Mississippi or the Saint Lawrence flows southeast across Texas.

Then it, too, is gone (below), leaving behind the massive fossil reefs of the Guadalupe Mountains National Park. There is no Florida yet; Alaska and Russia are one; the Caribbean is a malarial bog of proto-islands, choked with seaweed, overrun with electric eels and tide pools.

Somewhere humans are chipping flints together and hallucinating spaceships.

Till North America hits its Ice Age. Thousands of acres of frozen arches stand whistling in frigid winds above the future site of Washington DC. Humans huddle in caves – then move south, populating the New Mexican desert. Global sealevels drop, revealing caverns in the coasts of every continent.

The magnetosphere howls in the freezing air.

Then it’s today. New oceans continue to form. Major geological events continue to happen. Someday the coast of California will drag along the edge of Alaska, depositing pieces of Culver City in the front range.

Eventually the planet will melt, cities forming rivers of liquid stone.

It’s interesting in this context to note that, if the Antarctic ice cap melts, Antarctica itself may rise: “The continental shelf of the South Polar land lies four times lower than normal,” New Scientist reported, “suggesting that if the ice (more than a mile thick below sea level at some points) were removed, the continental surface would rise.” This is called post-glacial rebound.

Fascinatingly, Antarctica’s “present mountains would attain considerable heights and introduce new frictional opposition to prevailing winds, so new weather patterns would be created.”

In any case, every one of those maps above suggests about six hundred novels or short stories just waiting to be written; but the most exciting part of all of it is that we are already living in that world, of altered weather and island arcs, abraded coasts and rivers. It’s what we’re doing right now.

Beneath the house I write this in are seams of lost continents. Outside the place you read this in are moving unmapped geographies yet to come.

(Note: All maps in this post are by Ron Blakey, Professor of Geology, Northern Arizona University – perhaps, if enough people ask, we can get him to map North America as it will someday be).

[Images: The Taj Mahal, the

[Images: The Taj Mahal, the