[Image: Circle Line Pinhole 32, from Rob Gardiner’s inspired photographic project, Walking the Circle Line, London].

[Image: Circle Line Pinhole 32, from Rob Gardiner’s inspired photographic project, Walking the Circle Line, London].

Rupert Thomson’s recent novel Divided Kingdom is set in a world where the whole of Britain has been broken up into four sectors, the population itself forcibly “rearranged” according to emotional temperment.

Well-disciplined over-achievers are sent to one quarter; despair-wracked introspectionists another; pick-up truck driving nutters prone to violence take a third (I came I saw I lost my temper, its postcards read); and some other group I’m overlooking at the moment gets the last bit.

Walls and fences begin to appear; soon people complain of “border sickness” as they are further hemmed in by a series of Internal Security Acts. “Throughout the divided kingdom,” we read, “the walls of concrete blocks had been reinforced with watch-towers, axial crosses and even, in some areas, with mine-fields, which rendered contact between the citizens of different countries a physical impossibility.”

London itself is “divided so as to create four new capitals,” and each major bridge over the Thames is “fortified, along with watch-towers at either end and a steel dragnet underneath.” However, “in stretches where the river itself had become the border all the bridges had been destroyed. The roads that had once led to them stopped at the water’s edge, and stopped abruptly. They seemed to stare into space, no longer knowing what they were doing there or why they had come.”

[Image: From Under Blackfriars Bridge, London, by Rob Gardiner].

[Image: From Under Blackfriars Bridge, London, by Rob Gardiner].

There is even a “tourist settlement called the Border Experience” constructed near one of the crossings – apparently learning from Venturi, complete “with theme hotels, fast-food restaurants and souvenir shops.”

In one sector, all the motorways “had been converted into venues for music festivals or sporting events, and others had been fortified, then turned into borders, their tall grey lights illuminating dogs and guards instead of traffic, but for the most part they had simply been allowed to decay, their signs leaning at strange angles, their service stations inhabited by mice and birds, their bridges choked with weeds and brambles or, as in this case, collapsing altogether. In time, motorways would become so overgrown that they would only be visible from the air, half-hidden monuments to an earlier civilization, like pyramids buried in a jungle.”

[Image: Circle Line Pinhole 16, from Rob Gardiner’s Walking the Circle Line, London].

[Image: Circle Line Pinhole 16, from Rob Gardiner’s Walking the Circle Line, London].

While still a young boy, the narrator develops “border games” with a mate; they “prowl among the cement-mixers and scaffolding poles” next to “a section of the motorway that was in the process of being dug up,” and they use cardboard tubes to spy on guards stationed several acres away.

In any case, parts of Divided Kingdom read like descriptions of Dubai – or what Mike Davis refers to as Dubai’s “monstrous caricature of futurism,” as that city strives “to conquer the architectural record-books.”

There is something called the Underground Ocean, for instance. Thomson’s narrator and his entourage are led down into a basement warehouse, where they stand beside a lifeguard on a boardwalk in the dark:

The lifeguard’s voice floated dreamily above us. Any second now, he said, the scene would be illuminated, but first he wanted us to try and picture what it was that we were about to see. I peered out into the dark, my eyes gradually adjusting. A pale strip curved away to my right – the beach, I thought – and at the edge furthest from me I could just make out a shimmer, the faintest of oscillations. Could that be where the water met the sand? Beyond that, the blackness resisted me, no matter how carefully I looked.

“Lights,” the lifeguard said.

I wasn’t the only delegate to let out a gasp. My first impression was that night had turned to day – but instantly, as if hours had passed in a split-second. At the same time, the space in which I had been standing had expanded to such a degree that I no longer appeared to be indoors. I felt unstead,y, slightly sick. Eyes narrowed against the glare, I saw a perfect blue sky arching overhead. Before me stretched an ocean, just as blue. It was calm the way lakes are sometimes calm, not a single crease or wrinkle. Creamy puffs of cloud hung suspended in the distance. Despite the existence of a horizon, I couldn’t seem to establish a sense of perspective. After a while my eyes simply refused to engage with the view, and I had to look away.

“Now for the waves,” the lifeguard said.

It is interesting to note that, at the end of the book, in the Acknowledgements, Thomson cites S,M,L,XL by Rem Koolhaas as having been a literary resource.

[Image: Circle Line Pinhole 52, from Rob Gardiner’s Walking the Circle Line, London].

[Image: Circle Line Pinhole 52, from Rob Gardiner’s Walking the Circle Line, London].

While it seems rather obvious that the book is not meant to present the next likely development in national governance or urban planning, many readers – i.e. Amazon reviewers – seem upset by the premise, and repeatedly point out that this “could never happen.” But surely that’s not the point? As with all of Thomson’s novels the writing is exquisite, at times dreamlike yet descriptively precise; the book is also one of the few examples I can think of where I actually wished the book had been substantially longer (it’s 336 pages).

If you do read it, let me know what you think.

[Image: Circle Line Pinhole 64, from Rob Gardiner’s Walking the Circle Line, London].

[Image: Circle Line Pinhole 64, from Rob Gardiner’s Walking the Circle Line, London].

(Thanks to Steve & Valerie Twilley for the book! Meanwhile, for more of Rob Gardiner’s photographs, see Gardiner’s blog; I’m a particular fan of his London work).

Lawrence Weschler’s Convergence of Convergences Contest over at McSweeney’s revisits the above photo of a clear-cut forest in Sweden – where the void left behind by logging has visually reproduced the very thing that void destroyed. The return of the repressed, indeed…

Lawrence Weschler’s Convergence of Convergences Contest over at McSweeney’s revisits the above photo of a clear-cut forest in Sweden – where the void left behind by logging has visually reproduced the very thing that void destroyed. The return of the repressed, indeed…  [Image: A brief homage to

[Image: A brief homage to  [Image: Via

[Image: Via  [Image: Jeff Shea/

[Image: Jeff Shea/ [Image: Map of Greenland, courtesy of the

[Image: Map of Greenland, courtesy of the  [Image: The mountains of eastern Greenland: a future archipelago. Via

[Image: The mountains of eastern Greenland: a future archipelago. Via  [Image: Greenland’s thawing landscape; photo by Jeff Shea/

[Image: Greenland’s thawing landscape; photo by Jeff Shea/ [Image: From Keith Kin Yan’s

[Image: From Keith Kin Yan’s  [Images: Two shots of Copenacre Quarry, via Nick McCamley’s

[Images: Two shots of Copenacre Quarry, via Nick McCamley’s  [Images: Two more shots of Copenacre Quarry, via Nick McCamley’s

[Images: Two more shots of Copenacre Quarry, via Nick McCamley’s  Just a quick note of thanks to everyone who came out

Just a quick note of thanks to everyone who came out  If you’re in LA and you’re reading this before 3pm, Saturday, January 13th, consider stopping by the

If you’re in LA and you’re reading this before 3pm, Saturday, January 13th, consider stopping by the

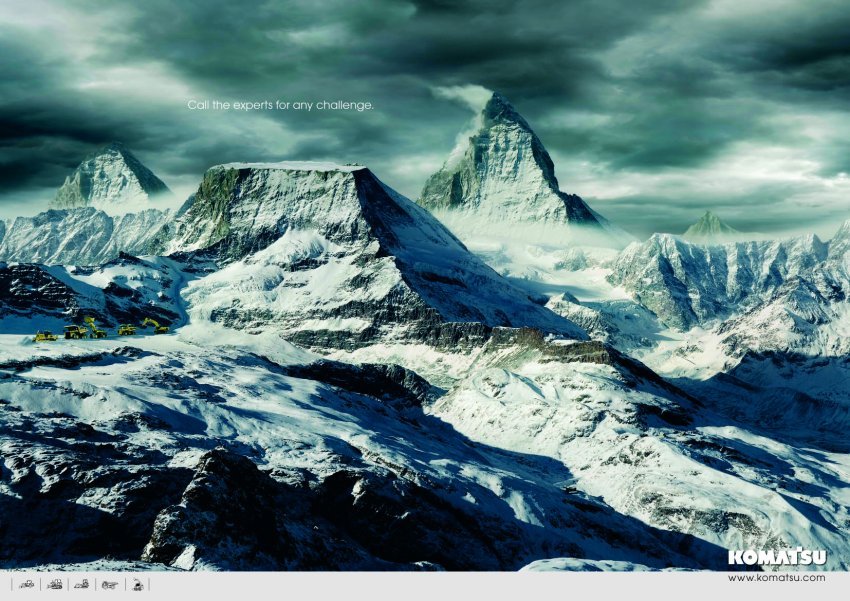

And there they are, driving away in yellow earth-moving equipment –

And there they are, driving away in yellow earth-moving equipment –  [Image:

[Image:  [Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: Circle Line Pinhole 16, from

[Image: Circle Line Pinhole 16, from  [Image:

[Image:  [Image:

[Image: