I’m back from London now to find the news cycle absolutely abuzz with so many interesting stories that it’ll be hard to keep up – but I’ll start posting the best of the best in a bit.

[Image: A photo from Jacob Carter’s ridiculously gorgeous River Thames Series].

[Image: A photo from Jacob Carter’s ridiculously gorgeous River Thames Series].

First, though, last week’s lecture was a blast; I talked way too fast, of course, bungling several points in the process, but, in the main, I had a great time and can only hope that everyone who came out on a Wednesday night in London – including my father-in-law! – to hear perhaps a bit too much about geology and not enough about offshore structures, or about the colonial politics of naming alien territories, or about urban iterative architecture, had a good time, as well.

The Bartlett may or may not be uploading a film of the lecture at some point, meanwhile; until then, a few notes from the talk can be seen courtesy of Matt Jones and Mark Simpkins. Also, if you attended BLDGBLOG’s recent lecture at SCI-Arc then you would have heard a lot of this before – but you would have missed out on instancing gates and billboard houses and the Indonesian mud volcano and China Miéville’s “slow sculptures” and what I thought was a really fun Q&A.

[Image: Another one from Jacob Carter’s River Thames Series].

[Image: Another one from Jacob Carter’s River Thames Series].

So here’s a huge thanks to Iain Borden for hosting the lecture, and to Alex Haw, both for setting it up and for introducing me. Expect more from Alex here on BLDGBLOG, by the way, hopefully soon.

Now: back to regular posting…

(Note: The title of this post is a line from London Orbital by Iain Sinclair).

The author “claimed to have become so intoxicated” by the fumes that “she was reduced to writing thrillers.” Indeed, the fumes grew so intense “that she was unable to concentrate on writing her highbrow novel, Cool Wind from the Future, and instead wrote a brutal crime story, Bleedout, which she found easier.”

The author “claimed to have become so intoxicated” by the fumes that “she was reduced to writing thrillers.” Indeed, the fumes grew so intense “that she was unable to concentrate on writing her highbrow novel, Cool Wind from the Future, and instead wrote a brutal crime story, Bleedout, which she found easier.”  [Image: Photo by Eran Brokovich for

[Image: Photo by Eran Brokovich for  I believe, as well, that I’ll be introduced by

I believe, as well, that I’ll be introduced by  It’s a speculative project, to be sure – but a fun one, and I can’t wait to see what comes up.

It’s a speculative project, to be sure – but a fun one, and I can’t wait to see what comes up.  Continuing:

Continuing: [

[

[Image:

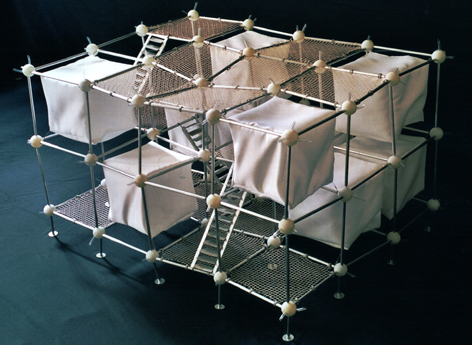

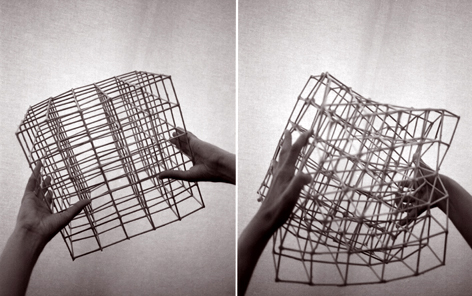

[Image:  [Image: Maison elastique by

[Image: Maison elastique by

[Images: More views of Elastic Houses by

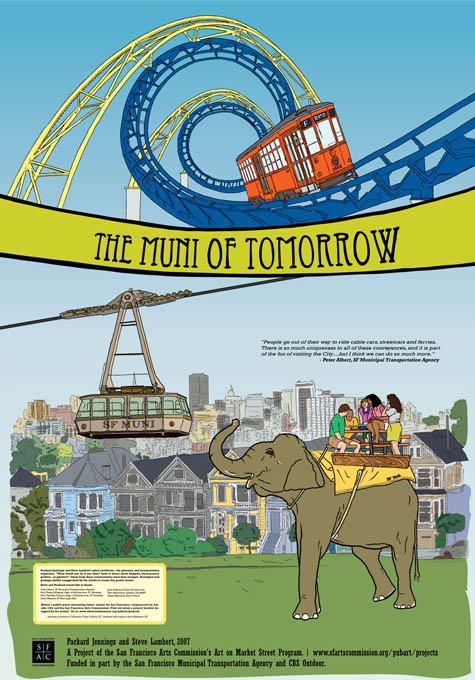

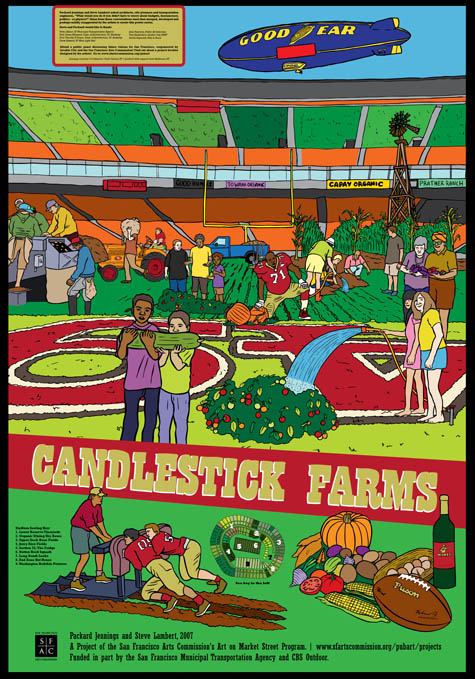

[Images: More views of Elastic Houses by  [Image: By Steve Lambert and Packard Jennings – you must

[Image: By Steve Lambert and Packard Jennings – you must  [Image: By Steve Lambert and Packard Jennings –

[Image: By Steve Lambert and Packard Jennings –

[Images: By Steve Lambert and Packard Jennings – view larger:

[Images: By Steve Lambert and Packard Jennings – view larger:  [Image: Photograph ©

[Image: Photograph © [Image: From

[Image: From  These “fields of shiny crops,” the

These “fields of shiny crops,” the  [Image: A rendering of the

[Image: A rendering of the

[Images: Two more views of the

[Images: Two more views of the  [Image: A structural diagram of the building’s exterior, unfolded].

[Image: A structural diagram of the building’s exterior, unfolded].