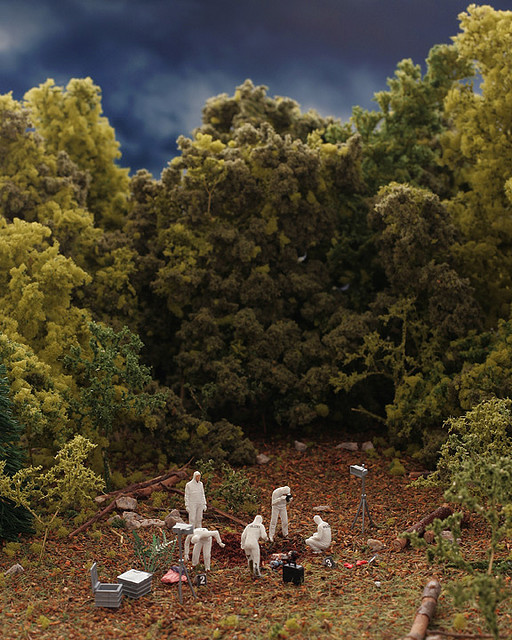

[Image: Photo by Gary Warner, from the cryptoforestry Flickr pool].

[Image: Photo by Gary Warner, from the cryptoforestry Flickr pool].

In his ongoing exploration of “the forest in the city,” Wilfried Hou Je Bek has produced a voluminous quantity of writings worth exploring in more detail, and so it is somewhat arbitrary to lead with this link; but the title of a recent post, “If the forest is empty so is the mind,” compelled me to point your attention to his blog Cryptoforestry (previously mentioned here).

Cryptoforesty, as Wilfried describes it in that post, emphasizes “the psychological effects of a forest” rather than the forest’s pure ecological function; indeed, he writes, “The point is not that wolfs and bears are needed to fulfill ecological functions that are now null and void, the point is that a forest with such animals fuels the imagination and adds zest to life, even to those who would never visit such a ‘full’ forest.” And, thus, he quips, “If the forest is empty,” devoid of its animal sentience, “so is the mind.”

Further, his point that European forests are now actually “being replenished from the east” with wild creatures is both politically symbolic and environmentally interesting.

[Image: Photo by Gary Warner, from the cryptoforestry Flickr pool].

[Image: Photo by Gary Warner, from the cryptoforestry Flickr pool].

The “What is a Cryptoforest?” essay is a virile and spirited defense of landscape ferality. Quoting at length and hoping to give a rhetorical sense of the writer’s interests, which range from the poetry of Gary Snyder to pre-Columbian rock art:

Cryptoforests are those parts of the city in which nature, in “secret,” has been given the space and the time to create its own millennia-millennia-old, everyday-everyday-new order by using the materials (seeds, roots, nutrients, soil conditions, waste, architectural debris) at hand. Cryptoforests are sideways glances at post-crash landscapes, diagrammatic enclaves through which future forest cities reveal their first shadows, laboratories for dada-do-nothingness, wild-type vegetable free states, enigma machines of uncivilized imagination, psychogeographical camera obscuras of primal fear and wanton desire, relay stations of lost ecological and psychological states. Cryptoforests are wild weed-systems, but wildness is equated not with chaos but with productiveness at a non-human level of organization. What starts with weed ends with a cryptoforest, and in between there is survivalism, with plants eking out a living against all odds, slowly but determinedly creating the conditions for the emergence of a network of biological relationships that is both flexible and stubborn, unique and redundant, fragile and resilient. Cryptoforests are honey pots for creatures that have no other place to go. Animals live there, the poor forage there, nomads camp there and the cryptoforester who has renounced the central planning commission re-creates there (free after Henri Thoreau). In the future, young people will no longer want to play in bands and they will become guerrilla gardeners and cryptoforesters instead.

“What starts with [a] weed ends with a cryptoforest”—the cryptoforest is a nearly all-encompassing botanical category for vegetation untamed. “The cardinal rule of cryptoforestry is that you can’t search for a cryptoforest,” we read. “You stumble upon them, they are already right in front of you.” Further, becoming sites of spatial folklore, cryptoforests are “always larger on the inside than they appear from the outside.”

[Image: Photo by Gary Warner, from the cryptoforestry Flickr pool].

[Image: Photo by Gary Warner, from the cryptoforestry Flickr pool].

Cryptoforestry offers fives diagnostic categories for this marginal terrain:

1) Feral forests (Planted tree zones, for instance along motorways, that have been allowed to become wild to the point that their wildness is outgrowing their manmadeness.) 2) In limbo forests (Tree-covered plots that feel like forests but technically probably aren’t; states of vegetation for which lay-language has no name.) 3) Incognito Forests (Forests that have gone cryptic and are almost invisible, forests in camouflage, forests with a talent for being ignored.) 4) Precognitive forests (Lands that are on the brink of becoming forested, a future forest fata morgana.) 5) Unappreciated forests (Forests regarded as zones of waste and weed, forests shaming planners, developers, and the neighbourhood. NIMBY forestry.)

These are less climax ecosystems than purgatorial ones, we might say—false gardens beyond cultivation, in which a different sort of nature is discovered growing “already right in front of you.”

The whole blog is worth bookmarking for later return.

(Consider joining the cryptoforestry Flickr pool).

[Image: One of the corners of Lebbeus Woods’s drawing room, courtesy of Lebbeus Woods].

[Image: One of the corners of Lebbeus Woods’s drawing room, courtesy of Lebbeus Woods].

[Image: “

[Image: “

[Image: Photo by

[Image: Photo by  [Image: Photo by

[Image: Photo by  [Image: Photo by

[Image: Photo by

[Image: Courtesy of

[Image: Courtesy of

[Image: From the

[Image: From the  [Image: From the

[Image: From the

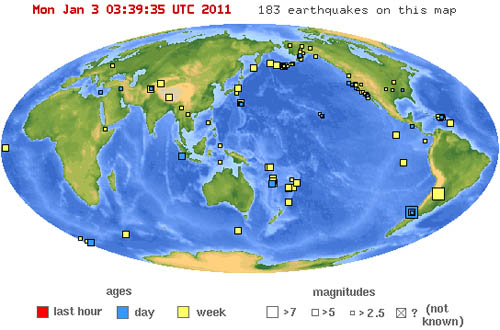

[Image: The USGS

[Image: The USGS

[Image:

[Image: