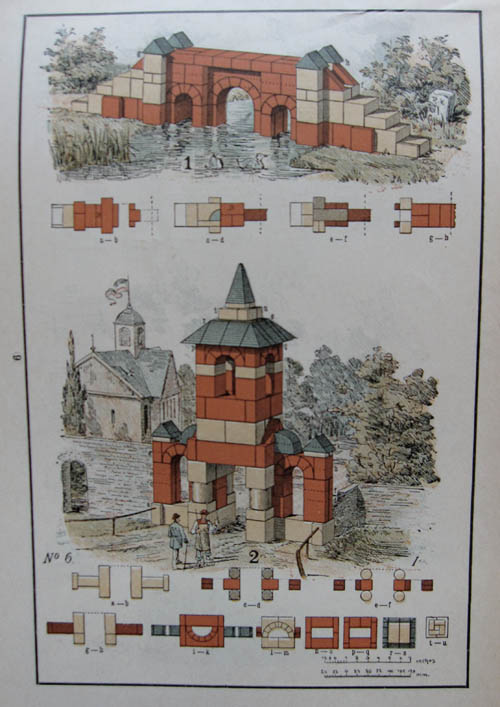

[Image: One of many pages from the voluminous archive of Richter’s toy manuals at the CCA].

[Image: One of many pages from the voluminous archive of Richter’s toy manuals at the CCA].

While down in the CCA archives last week, I had some time to explore a number of old instructional booklets for wooden children’s toys.

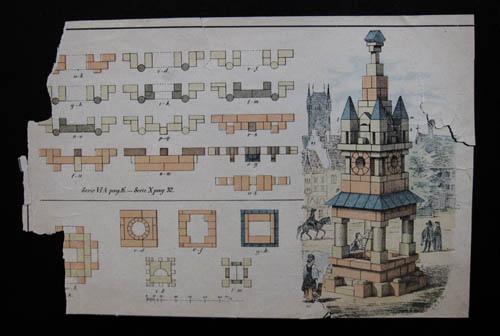

One such book, called The Art of Architecture of Building With Given Model Stones, explains that “It will be seen from the title of this book that it is intended to be a guide in the construction of larger buildings with the aid of model stones, indefinite in number, but of certain fixed shapes.”

[Image: Page from a Richter’s toy manual; courtesy of the CCA].

[Image: Page from a Richter’s toy manual; courtesy of the CCA].

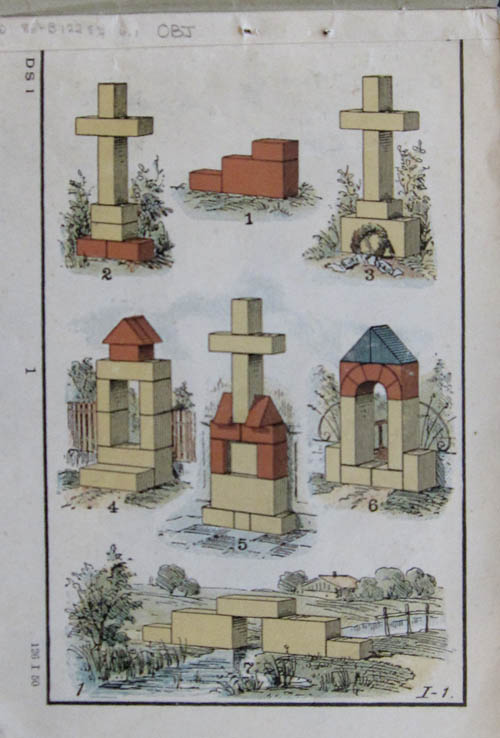

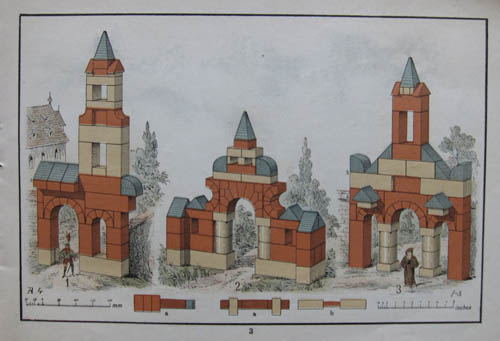

From the very basic—

[Image: An early stage in assembling Richter’s “anchor blocks”; courtesy of the CCA].

[Image: An early stage in assembling Richter’s “anchor blocks”; courtesy of the CCA].

—to the much more complex—

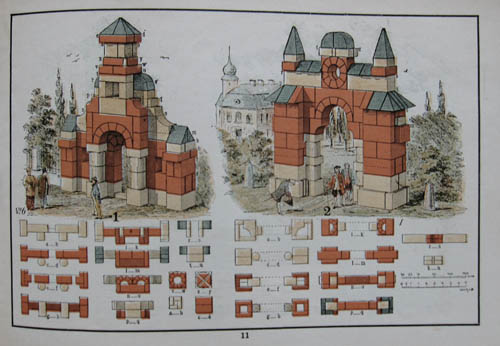

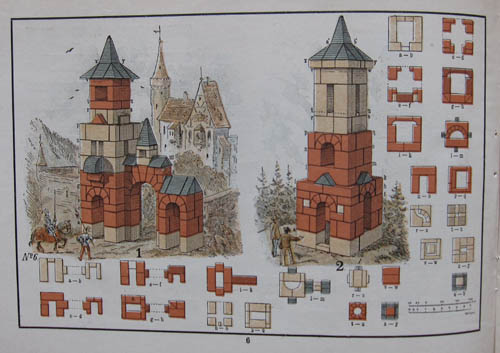

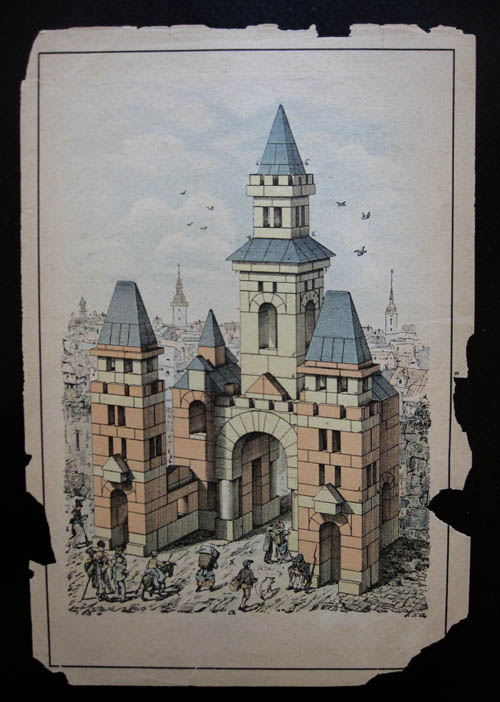

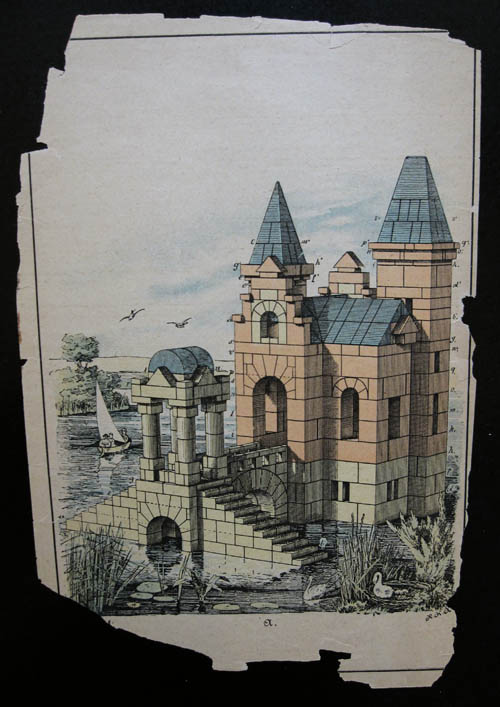

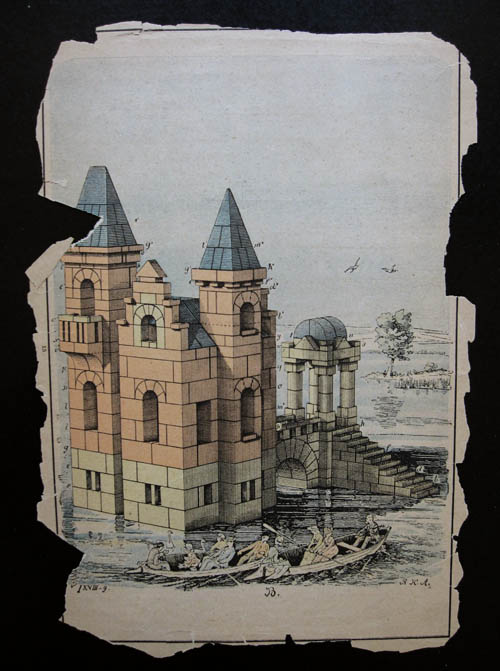

[Images: Complex spatial objects from an advanced stage of the Richter’s toy system; courtesy of the CCA].

[Images: Complex spatial objects from an advanced stage of the Richter’s toy system; courtesy of the CCA].

—these toys were imagined as pedagogical tools for the training of the young human mind.

As such, Richter’s toys did not at all seem out of place down there in the CCA archive, stored near other such fading boxed sets as the “Object-Teaching Forms and Solids” of A.H. Andrews & Co., Chicago, dating from 1890, or even “Kinsey’s Ornamental Lock Block and Toy” set, from 1875, which unfortunately used tiny wooden swastikas—hundreds of swastikas—to teach children how they, too, can fill space with interlocking, modular parts.

[Images: Into the hypnotic spreads of a geometrical universe; courtesy of the CCA].

[Images: Into the hypnotic spreads of a geometrical universe; courtesy of the CCA].

Produced in the late 1800s by a company called Richter’s—”Designed and Executed by Dr. Richter’s Art-Department,” then located at 74-80 Washington Street, New York, NY—the blocks and their instructional manuals that you see here were no mere playthings; they were marketed as intellectual stimulants, Frobelian educational props, for teaching children nothing less than how to think.

At this point I might offer a slightly long quotation from the Los Angeles-based Institute For Figuring about the origins and purpose of Frobelian education:

Most of us today experienced kindergarten as a loose assortment of playful activities—a kind of preparatory ground for school proper. But in its original incarnation kindergarten was a formalized system that drew its inspiration from the science of crystallography. During its early years in the nineteenth century, kindergarten was based around a system of abstract exercises that aimed to instill in young children an understanding of the mathematically generated logic underlying the ebb and flow of creation. This revolutionary system was developed by the German scientist Friedrich Froebel whose vision of childhood education changed the course of our culture laying the grounds for modernist art, architecture and design. Le Corbusier, Frank Lloyd Wright and Buckminster Fuller are all documented attendees of kindergarten. Other “form-givers” of the modern era—including Piet Mondrian, Wassily Kandinsky and Georges Braque—were educated in an environment permeated with Frobelian influence.

I might also then suggest that we seem sorely lacking today in analogue children’s toys inspired by an instructional need to teach lessons in space, relation, cause, effect, etc.

[Images: Variation, adaptation, memory; courtesy of the CCA].

[Images: Variation, adaptation, memory; courtesy of the CCA].

In any case, Richter’s blocks worked, we’re told by the company itself, because “instruction must be united with amusement.”

Indeed, an entire philosophy of child-rearing is outlined in these toy manuals. They seem to have been written more with the purpose of explaining how the human brain processes information than for telling future consumers how to use their new toys.

They are not product manuals at all, then, but manifestos of human cognitive development.

[Image: Cognitive tools in the guise of toys, manufactured by Richter’s; courtesy of the CCA].

[Image: Cognitive tools in the guise of toys, manufactured by Richter’s; courtesy of the CCA].

Richter’s system, in particular, “trains [children] to habits of orderliness and tidiness, especially when they know what they must keep the boxes they already possess intact, if they wish to be able to build the designs of the next Supplement Box.”

Raised in a world of these carefully regulated Supplements, Richter-building children learn to master consumer self-control and the rudiments of cognition itself—as if undergoing training in some woodblock remake of Inception.

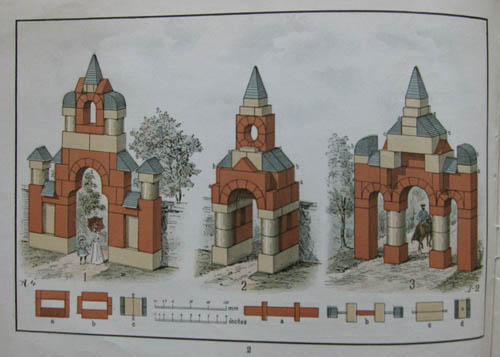

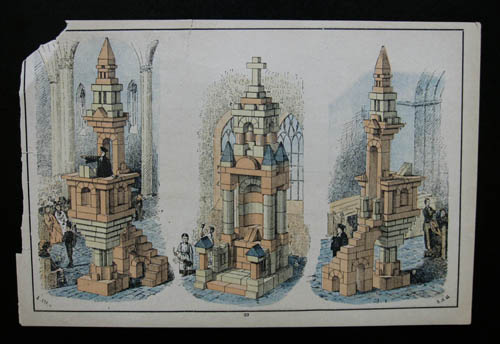

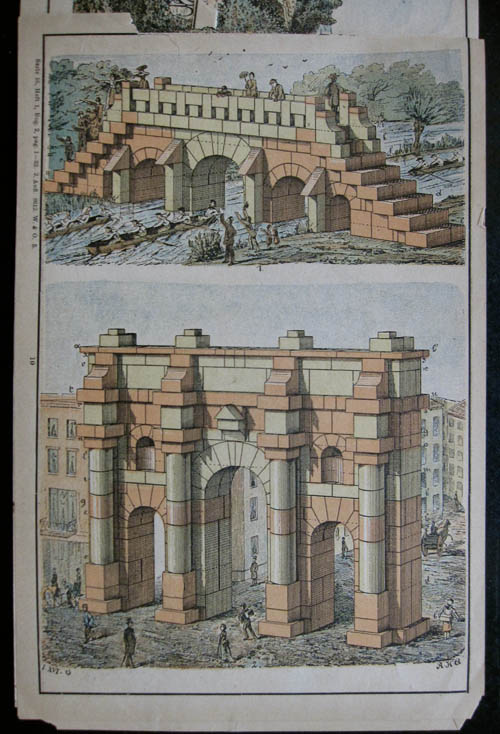

[Images: The same building, rotated 90-degrees; by Richter’s. Courtesy of the CCA].

[Images: The same building, rotated 90-degrees; by Richter’s. Courtesy of the CCA].

There are ample warnings against straying from these directions. Not paying attention to the order of Supplements, for instance, as if your child is being initiated into a Masonic cult of basic geometric shapes, means that the child’s mind may become lost.

The children should not be permitted to construct [the designs in this book] until they have thoroughly mastered the First Stage. In this way the little architects, even the smallest of them, will be able of their own initiative successfully to overcome the various architectural problems of the present Book, and parents will soon get to recognize the importance of the Anchor Blocks as a means of inducing children to think for themselves.

However, “When once they are mastered, building becomes an unfailing source of joy as well as of instruction for children and their elders alike.”

At that point, the successful little builder “should show his parents as many well constructed buildings as possible and get them occasionally to join him in building.”

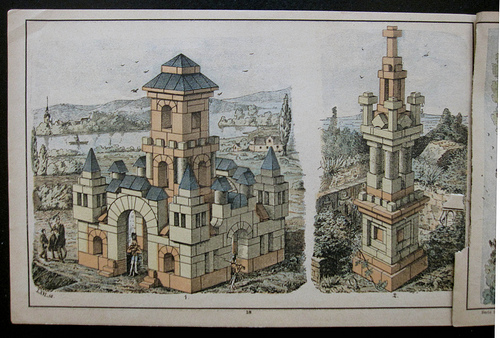

[Images: Another structure, rotated 180-degrees for ease of spatial perception; courtesy of the CCA].

[Images: Another structure, rotated 180-degrees for ease of spatial perception; courtesy of the CCA].

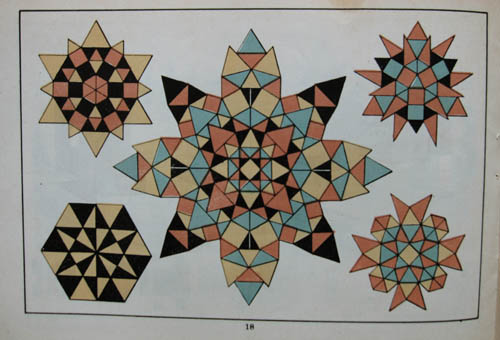

Note the gender. These toys were specifically marketed as cognitive training devices for boys. Girls were instead given flat, two-dimensional patterns, called “mosaic-games,” not at all unlike quilting templates, to play with, instead.

[Image: A “mosaic-game” from Richter’s; courtesy of the CCA].

[Image: A “mosaic-game” from Richter’s; courtesy of the CCA].

“We have also introduced a number of most interesting marble mosaic-games specially designed for girls,” Dr. Richter’s guidebooks explain. “Contained in a handsome wooden box, [these consist] of a laying-plate and a number of specially shaped stones, which are made with the utmost precision. The patterns which can be laid with these stones are quite charming and often produce most striking and unexpected effects.”

This vision of girls reduced more or less to the status of imbeciles, tripping out on “quite charming” patterns while pushing little pieces of colored stone around on a “laying-plate,” would be a hilarious anachronism if it wasn’t also so tragic.

Men will learn to build and inhabit three-dimensional space; women can make mosaics, push rocks around, sew quilts together, and drool.

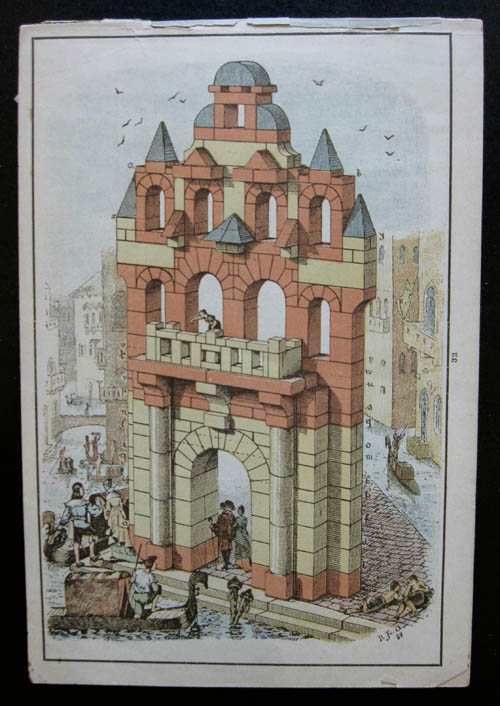

[Image: Richter blocks, courtesy of the CCA].

[Image: Richter blocks, courtesy of the CCA].

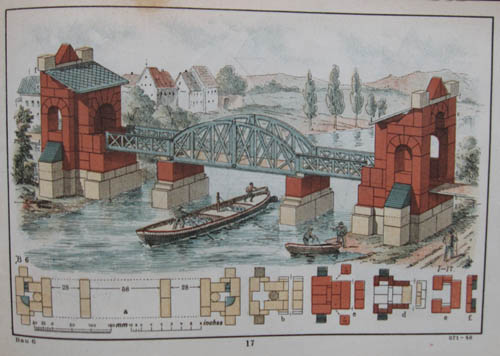

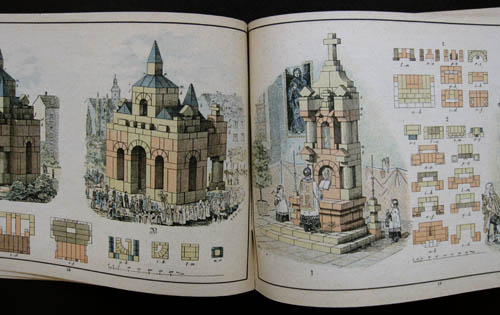

I photographed nearly one hundred pages of designs from the Richter series; I’ve included just a few here to give a sense for the overall visual language of the pavilions, churches, altars, towers, bridges, houses, walls, and more into which the woodblock pieces were meant to be assembled.

[Images: Richter blocks, courtesy of the CCA].

[Images: Richter blocks, courtesy of the CCA].

However, if this sort of thing interests you beyond a single blog post, I’d recommend taking a look at the Institute For Figuring’s Inventing Kindergarten page; but I would also point you toward the CCA’s exhibition Potential Architecture: Construction Toys from the CCA Collection (1991-1992), with architecturally-themed children’s toys selected by Norman Brosterman.

A pamphlet was published to coincide with that show, and is itself worth checking out.

[Image: Courtesy of the CCA].

[Image: Courtesy of the CCA].

In describing the exhibition, the CCA wrote that Brosterman chose to focus on “twenty-one construction toys, made in the hundred years from 1850 to 1950.” These are toys, now held in the CCA’s underground archives, “that were designed to challenge a child’s creativity. The toys illustrate how children learn to invent relationships between space, structure, and building forms, and hence to better understand the world around them.”

Each one of these modular toy sets “invited children to organize its prefabricated toy buildings into entire cities”—a remark that once again brings to mind those early, all too brief training scenes seen in Inception, where Leonardo DiCaprio describes the flexible architecture of urban maze-creation to a pupil named Ariadne, who then takes to her lessons suspiciously well.

But might a dream academy of Inception-scale urban alteration be the Frobelian education to come, for a future, highly fortunate generation of children? In a kindergarten of machine-assisted sleep, they will assemble cities indefinite in number, but of certain fixed shapes, outdoing any urban form that’s come before.

Nothing wrong with encouraging two-dimensional pre-quilting (which should have nothing to do with drooling either by the way). The color-play and geometrics in that kind of exercise builds brain cells too. That said, too bad both boys and girls weren't encouraged to enjoy both kind of interesting activities.

Otherwise a quite fascinating post, with fantastic graphics. Great find.

Nothing wrong with encouraging two-dimensional pre-quilting

Indeed—but the implied stratification of educational tools, based upon a feminine inability to comprehend (and thus appreciate) three-dimensional space, comes off as quite belittling—at least to me—in the context of these booklets' rhetorical hyperbole about "little architects" and their growing minds.

Fantastic post – thanks for taking the trouble to share so many photos. I won't look at my children's simple building blocks in quite the same way now. Also thanks for the pointer to the CCA pamphlet, they have some treasures there.

My daughters (six and eight) seem instinctively to regard "educational" toys as pedantic and patronizing, and prefer rocks, sticks, pencils, brushes, ink, scratch paper, scissors, cardboard and hot glue. Even unit blocks appear to strike them as semiotically overdetermined.

I am therefore disposed to regard "analogue children's toys inspired by an instructional need to teach lessons in space, relation, cause, effect, etc." as a bit of a (well-intentioned) nineteenth-century artifact. Set your children up with tools and supplies you yourself would be willing to use (and some safety guidelines and monitoring) and they'll do just fine.

I might also then suggest that we seem sorely lacking today in analogue children's toys inspired by an instructional need to teach lessons in space, relation, cause, effect, etc.

I don't think this is true. We have a plethora of building toys, and toys that are based on various forms of motion and propulsion, and most of them make some sort of educational claim somewhere in their advertising material. What I think is true is that the specific goals of educating children in spatial and physical concepts are being buried in a pile of "literacy" slogans.

It's also true that the kindergarten has largely robbed of these activities(in the US at least, and largely due to the politics and economics of the No Child Left Behind Era). No more hollow blocks and "unit" blocks (the marvelously proportioned wooden blocks with which you can build forever, if you have enough of them): just scripted alphabet activities for the five year olds.

So it falls to the families to be informed enough, interested enough, and prosperous enough, to provide children with building toys.

And the genderization continues.

So are women masters of plan and men masters of space? Wonder if that thought holds any validity…

Unrelated, but tangentially interesting, I belive these manuals appear in Jan Svankmajer's film of Jabberwocky.

Graphically they are rather lovely, with the naive coloured blocks set against a 'proper' illustration of a realistic setting. I'm not sure what to think about this, but I suspect Stirling would have approved.

In light of the maths bonanza in quilting, or tiling, or map colouring, there's at least some ambiguity about the harms in gendering of toys in this case.

The assumptions being fingered here leave opportunities for cognitive development for girls. It's possible the apparent obviousness of the sexism is illusory.

I'd say the gendering may be reasonable, and that gendering generally is reasonable in some instances, tho' not in many others. The larger fact may be that thought is given to the girls development. That's also historically interesting.

I was surprised to find that these building blocks are still for sale.

http://www.eurotoyshop.com/Toys/AK-X8A/Anchor/Anchor-stones-expansion-set-8A.html

And yes, advances sets REQUIRE the purchase of the basic sets. And they are not cheap.

There should be a virtual-game involving real-time graphic rendering with essentially Legos: An almost-Inception inspired game where kids can control Lego-built cities with simple movements of their hands and body.

Like a mix of Blender, Legos, and Microsoft's Kinect system.

One problem though is the use of 3D graphics at young ages, since it's been shown youngster's eyes are still developing, and can't truly handle 3D (as in movie graphics, not real life 3D).

Great stuff! Love all the images, my goodness, I love the colors! I wouldn't be too worried about the swastikas, tho, prior to the nazi's they were seen as peace symbols, thus, very good for the young minds (1875 I think you said they were from). I would love love love to play with these.

Geoff, I would agree with Linda and go further to say that the mosaics actually have much more to do with the last half century of architecture (from Buckminster to Zaha) than the repetitive load-bearing blocks do. The gender segregation is only belittling within the frame of the cognitive development model being sold here (linear 3D structure referencing hierarchical social structure (church/state), etc). The mosaics remind me of FOA's envelopes, all the tessellation projects of the 00s, the relationship between fractal geometry and emergence theories a la Delanda, etc etc.

Don't be so shocked at patriarchal attitudes of previous intellectual eras (What – White men exploited and insulted everyone else for centuries? – no way!) that you miss the actually interesting and paradoxical aspects of their oh-so-never-completely-died-out arguments.

Thanks Geoff.

Upwards,

Mitch

Unfortunately such gender stereotyping of toys is far from being anachronistic. Parents, toy manufacturers and society in general seems to be convinced that there is a fundamental difference in the workings of the male and female brain and that females are charming, decorative klutzes with no spatial awareness whatsoever. Frankly a modern girl would be lucky to get a toy that encouraged her to think about maths and any colour that wasn't pink.

I think your blocks are in this commercial. Check out 50 seconds in or so.

Your article inspired me to do some research. I found some interesting links.

There is a high-quality archive of scans of the building manuals, fan magazines, and more here –

http://cva.flying-cat.de/

An extensive treatise here –

http://www.ankerstein.ch/downloads/CVA/Book-PC.pdf

And a community fan page here

http://www.ankerstein.org/

I am curious – how would these games translate into what is relevant for today's society? With so many movements and widespread beliefs into survival on the land beneath your feet rather than depending on the system to provide for the well-being (i.e. shelter, food) it would be awesome to bring a variation of the building block game to a child that would focus on the construction of an environment where an individual or a minimal group of people can live and function.

does this make sense?

does something like this already exist?

(I am thinking of the recent cyborg post + sustainability)

I also really love this post and agree that such games ought to remain encouraged in kindergartens. However, as a college student, I feel that the presence of these building blocks in classrooms would even improve the quality of creative and conceptual output in the works of art students; and really, just about anybody if only such exercises were taught and encouraged.

Drool baby, drool. On a more serious note, compared to the stuff of an even earlier age, this is positively revolutionary. Adults joining in kids' games? Standardized pieces? Free-form construction? Look in the bright side, really.