[Image: The Cloud Project van by Zoe Papadopoulou and Cathrine Kramer].

[Image: The Cloud Project van by Zoe Papadopoulou and Cathrine Kramer].

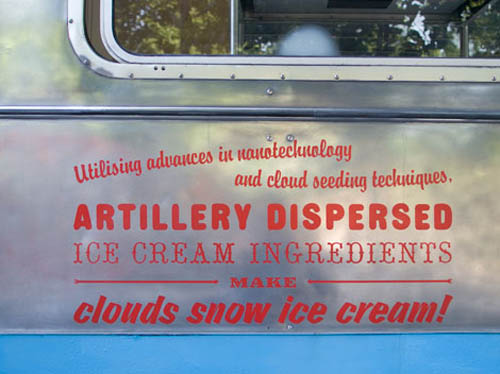

Like a whimsical hybrid of molecular gastronomy and Glacier/Island/Storm, the Cloud Project by Zoe Papadopoulou and Cathrine Kramer, design-interaction students at London’s Royal College of Art, would use “artillery dispersed ice cream ingredients,” fired from roof-mounted cannons, “to make clouds snow ice cream.”

[Images: From the Cloud Project by Zoe Papadopoulou and Cathrine Kramer].

[Images: From the Cloud Project by Zoe Papadopoulou and Cathrine Kramer].

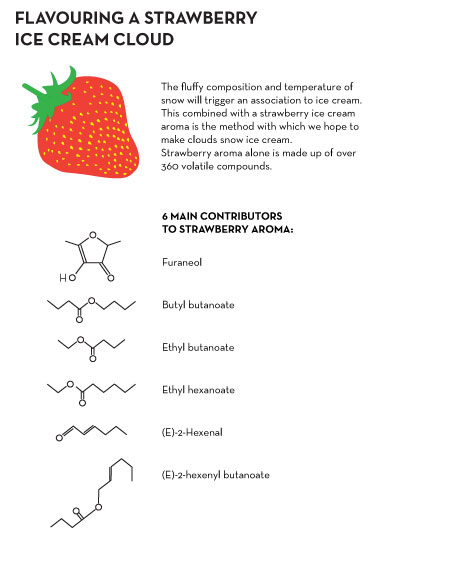

The van’s projectile clouds of aerosolized nanotechnology would kick-start snowflake formation high above—seemingly inspired by the cloud-producing exhalations of open-ocean algae—but they would also then scent the resulting snowfall with the aroma of fresh strawberries.

The result? Ice cream, delivered soft, cold, and delicious, falling straight from the afternoon sky. Perhaps we’ll soon all need ice cream gloves.

[Image: A how-to guide for precipitating strawberry ice cream by Zoe Papadopoulou and Cathrine Kramer].

[Image: A how-to guide for precipitating strawberry ice cream by Zoe Papadopoulou and Cathrine Kramer].

Oddly, BLDGBLOG proposed a variant on this—scented snow—a few years back, so it should come as no surprise that I think it’s at least worth a shot. After all, what could possibly go wrong?

But it’s worth asking what other foodstuffs might also be made to precipitate directly from the summer sky—when agriculture gives up the ghost, say, or once our planetary soils have been entirely depleted, could we someday farm the sky? Aerocultural precipitation: nutrition fresh and direct from the planet’s atmosphere.

And what a strange planet it would be if this somehow sparked runaway ice cream climate change: unstoppable drifts of Chunky Monkey filling the streets of Montreal, vast glaciers of the stuff carving valleys through Antarctic plains.

(Thanks to Liam Young for the tip! Speaking of food, meanwhile, don’t miss the previous post about this coming weekend’s quarantine banquet).

[Image: From a previous

[Image: From a previous  [Image: From a previous

[Image: From a previous  [Images: Photos from previous

[Images: Photos from previous  [Image: From a previous

[Image: From a previous  [Image: O.T. (2006) by

[Image: O.T. (2006) by  [Image: Abstract thought is a warm puppy (2008) by

[Image: Abstract thought is a warm puppy (2008) by  [Image: From

[Image: From

[Images:

[Images:  [Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: From

[Image: From  [Image:

[Image:

[Images: From

[Images: From

[Images:

[Images:  [Image: The CAVE at the Desert Research Institute in Reno, now called the

[Image: The CAVE at the Desert Research Institute in Reno, now called the

[Image: Daniel Coming, Principle Investigator of the

[Image: Daniel Coming, Principle Investigator of the  [Image: Touring virtual light].

[Image: Touring virtual light].

[Image: Cthulhoid satellites appear in space before you, rotating three-dimensionally in silence].

[Image: Cthulhoid satellites appear in space before you, rotating three-dimensionally in silence].

[Images: Photos by BLDGBLOG and

[Images: Photos by BLDGBLOG and  [Image: The

[Image: The