An article by Sebastian Rotella in the L.A. Times this past weekend presented readers with an interesting example of what might be called infrastructural interpretation.

[Image: Photo by ohhector, available through a Creative Commons license].

[Image: Photo by ohhector, available through a Creative Commons license].

On the one hand, Rotella suggests a fascinating way to explore the spatial role of the European train station in 20th century political thrillers.

Citing the novels of Eric Ambler, Graham Greene, and John Buchan, and referencing early Alfred Hitchcock films, Rotella demonstrates how it might be possible to foreground certain architectural forms – the train shed, or, perhaps, the multistory car park, the highway flyover, or the maximum security prison – in the process of writing cultural histories.

A short history of novels partially set inside planetariums. A spatial history of films set in shopping malls… with an introduction by Zach Snyder.

In this case, of course, it’d be a political microhistory of the European train station – and someone could very easily get a PhD out of such a scenario: The Train Shed as Depicted in Film, Games, and Literature: An Architecture of Encounter.

But the second point of interest here for me is more political. And that’s the fact that, for something published in the United States – and in Los Angeles, no less, kingdom of the private automobile – the article exhibits a depressingly obvious distrust in the municipal spaces of public transport.

In other words, the article goes on to describe the European train station – and train travel more generally – as a threatening bastion of non-white otherness that has infiltrated the modern city. Moroccans, after all, live near certain train stations… and Muslims sometimes ride those very trains…

“Moreover,” Rotella points out, “train stations tend to be in working-class immigrant areas where desperadoes find shelter, weapons, false documents and other tools of the trade. The Gare du Midi, on the southern edge of downtown Brussels, is a good example. A few Spanish and Italian shops remain from previous migrations, but the personality of the neighborhood today is Moroccan and Turkish.”

Indeed, Rotella further suggests, that otherwise unthreatening train station near you might even serve as spatial host to a “leftist-Islamic militant alliance” – never mind the fact that Islamic terror is almost universally committed against traditional leftist political goals (whether this refers to the separation of church and state or to gay rights and female suffrage).

But Al-Qaeda, in this way of interpreting European train infrastructure, is something like the passenger from hell – Islamic militarism riding amok, exploding bombs on high-speed routes and “slaughtering” innocent bystanders.

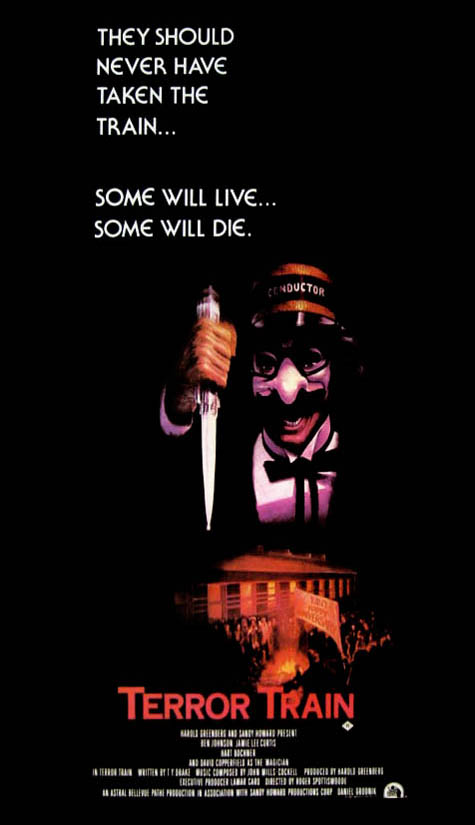

[Image: It’s Terror Train. In the future they might even serve couscous].

[Image: It’s Terror Train. In the future they might even serve couscous].

“Trains, stations and the gritty neighborhoods that surround them are often the backdrop to danger,” Rotella warns. Specifically, “trains and their stations have played a key role in modern-day plotting and attacks by Islamic terrorists.”

Of course, Mike Davis’s recent history of car bombs might offer a slightly different take on the relative dangers of various transport infrastructures – but I digress.

This would never happen in the United States, the subtext of Rotella’s argument seems to suggest, and it never will… provided we never build more public train stations.

In this context, President Barack Hussein Obama’s tentative interest in funding an American high-speed train network takes on rather spectacular political implications – at least as long as one lives in fear of a “leftist-Islamic militant alliance” being forged amongst the screaming wheels of modern railroad yards.

Osama bin Laden is alive and well… and securing more funding for Amtrak.

One man, we actually read – a man accustomed to train travel and with a penchant for political violence – “drank tea and ate couscous while allegedly hatching multimillion-dollar holdups, arms deals, money-laundering schemes and terrorist plots.” He ate couscous “in the kebab joints” near Belgium’s Gare du Midi, and he daydreamed scenes of near-supernatural violence.

He would arrive upon the world stage, enshrouded in robes of blood.

In any case, I don’t mean to sound over-eager to ridicule this story; after all, train stations are heavily populated sites of public gathering, and thus very effective targets for terrorist plots. But does this also make them terrorist breeding grounds?

Can train stations really represent both the secular invasiveness of big-government bureaucracy and violently independent religious conservativism?

Rotella’s implication here – that all train stations are somehow, in and of themselves, infrastructural acts of invitation to a vampiric immigrant presence that secretly hopes to inflict evil, thus equating train travel with international Islamic terrorism – seems very obviously motivated by ideology, not intellectual clarity or rational analysis.

Which is too bad, because a cultural history of the train station – as a site for political intrigue and so on – actually sounds incredibly interesting to me. At the very least, one could start a Wikipedia page for “political plots hatched in train stations,” or “murders committed in parking garages,” or “bombed shopping malls” – focusing on the infrastructural spaces within which certain major types of crime have been planned or committed.

Even more specifically, is there a spatial taxonomy for spy stories – and what types of structures seem repeatedly to appear?

Alas, Rotella’s article seems too besotted with AAA to view train travel as anything but a threat to national security.

The train station is a compelling prism for viewing political cultural & cultural history. I don't have a thriller to offer–but Sebald's Austerlitz is a book that comes to mind, layered as it is with considerations of the train station as a site of meeting & leave-taking, memory and forgetting.

of course, completely neglecting things like the Bologna bombings of 1980, committed by right wing terrorists with links to Operation Gladio…

the rest is just borderline racism, with a large dose of Eurabian nonsense.

regarding train stations, I'm always fascinated by the design anxiety they provoked in the early years (mid 19th C.), with their sheds furtively hidden behind Victorian edifices in a way that wasn't considered particularly necessary for other similar iron'n'glass constructions (exhibitions, glass-houses etc…), although this is also a factor of location, commerce, etc. as much as style.

It does sound like a good hypothetical Ph.D, definitely, I'd be very surprised if it hasn't been done many times before…

Sites of dense social and infrastructural exchange seem to be full of narrative potential. Whether tracing the roots of train travel in order to glean insights for the future of sustainable mobility or re-writing past history as a xenophobic rant on the dangers of public transportation, these spaces inspire great potential for creating meaning.

In a city like Cleveland, which is shrinking in population, the excess infrastructure poses interesting questions regarding future use. The initial use for many infrastructural spaces may no longer be desired or even possible, so what new stories can be written to reactivate them? Or should they just be sealed and forgotten to encourage critical mass in other fledgling places? A community design/build charrete this fall at Kent State University will investigate the potential reuse of the vacant trolley level of the Veterans Memorial Bridge in Cleveland. http://www.cudc.kent.edu/blog/?p=589#more-589 No doubt, spaces like these will continue to be fertile infrastructures for assembling new stories.

I fear that Murphy's notion that railway train-sheds were "furtively hidden behind Victorian edifices in a way that wasn't considered particularly necessary for other similar iron'n'glass constructions" because of "design anxiety" is as much of a myth as the canard that respectable people covered piano legs for fear that it would lead young. cf "Inventing the Victorians"

Railway hotels were a profitable speculative development, but they needed to have daylighting to their public rooms and to be highly visible – hence they were generally located as the most prominent element in most mid-19th century railway terminus developments when these things were still done on strictly commercial terms rather than to curry favour with civic improvers.