Still embedded somewhere in the shores of California, buried by more than a century of sand, are lost hydroelectric machines.

[Image: The Pacific Wave Motor, via the San Francisco Western Neighborhoods Project].

[Image: The Pacific Wave Motor, via the San Francisco Western Neighborhoods Project].

Deep in the prehistory of green energy technologies now being researched by Alexis Madrigal for his forthcoming book, there is a whole series of devices intended to generate power from the sea.

Precursors of today’s interest in tide power, these were “wave motors” and mechanized basins that turned the coast into a series of timed catchment reservoirs. The landscape itself became a machine.

One of the earliest patents filed for such technology was by Oakland resident Henry Newhouse in 1877. The purpose of his machine was “[t]o utilize the tide for a water-power,” his patent text read, as quoted by the San Francisco-based Western Neighborhoods Project, “and preserve a continuous power by means of the arrangement of a reservoir to catch the water at high-tide, and a discharge-basin to let the water out at low tide and shut it out while the tide is rising.”

Like something designed by Smout Allen, tunnels would be drilled through littoral rockfaces, even as natural bays were both expanded and reinforced. The coastline is soon a linked sequence of valves through which the tides can flow, generating electricity as they pass through a maze of elevated waterwheels and pumps.

A great example of this type of wave motor comes to us from “the Armstrong brothers”; it was built on the coast of Santa Cruz in 1898. Quoting the Western Neighborhoods Project‘s description of that project:

The Armstrongs’ wave motor, an oscillating water column, was built inside the cliff. They had dug a thirty-five by six foot hole into the side of the cliff that ran to a level below low tide. From there another tunnel connected it with the ocean. Inside of the thirty-five-foot well was a pump, and attached to that a 600-pound float. When the waves crashed on the shore, they forced water through the tunnel and up the well, lifting the float, opening the valve and filling the pump. As the water receded, the well water would fall, dropping the pump and the float. The valve would close and the piston, under the weight of the float, forced the water through a pipe to a tank on the hill.

Certain to puzzle future archaeologists, “The only part of the wave motor that remains today is the thirty-five-foot deep well in the cliff.”

In other words, what now appear to be eroded cliffs and chipped coastal plateaus are actually derelict machine parts from the 19th century.

[Images: The Santa Cruz Wave Motor, originally from Scientific American; via John Haskey].

[Images: The Santa Cruz Wave Motor, originally from Scientific American; via John Haskey].

Take Adolph Sutro’s “Aquarium” project, eventually subsumed into his larger quest to create the Sutro Baths: Sutro’s “tide machine was built inside the rocky bluff at Sutro Cove that was then being referred to as ‘Parallel Point’.”

From a natural shelf 17 feet above mean tide level, a catch-basin was built to catch water from three directions. A canal, 8 feet high and 153 feet long with a downwards slope of 3 feet in a hundred carried the ocean water from the catch-basin to the settling basin on the beach. The settling basin, built of cement and of rock taken from boring the canal, was 80 feet long, 40 feet wide and 10 feet deep. It held 250,000 gallons.

One might say that these “wave motors” were a kind of prosthetic stratigraphy upon the surface of the earth; left to their own devices, perhaps in a million years they’d even fossilize.

In other examples of this phenomenon, however, the machines weren’t embedded into the geology of the landscape; they were instead constructed, Constant-like, offshore on wooden piers.

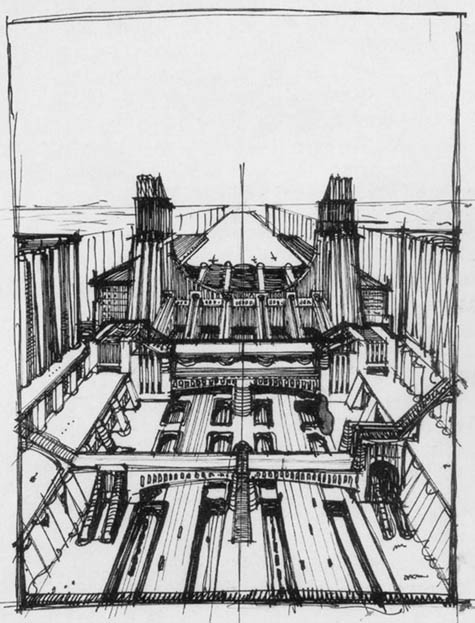

[Image: Constant’s New Babylon… reimagined as an offshore wave power farm].

[Image: Constant’s New Babylon… reimagined as an offshore wave power farm].

“Most notable” of these designs, we read, “was the Starr Wave Motor of Redondo Beach which began construction in 1907. It was a large project that hoped to supply power for six counties. In the end, the enormous machine collapsed in 1909 because of the flimsy construction of the pier on which it was attached.”

As the Western Neighborhoods Project continues, this was actually just one of many of “the wave motors of southern California.”

Included amongst that sub-class were the Wright Wave Motor of Manhattan Beach (built in 1897), the Reynolds Wave Motor of Huntington Beach (built in 1906) and the Edwards Wave Motor of Imperial Beach (built in 1909). “The Wright Wave Motor is the only one of these Victorian era wave motors still in existence,” we read; however, incredibly, it is now “buried in the sand at the foot of the present pier in Manhattan Beach.”

How fascinating to think that beneath the sand are strange devices long since forgotten by the general public; a retiree out for a stroll one day with a metal detector receives incredibly strong signals from a certain stretch of forlorn coastline – only to begin excavating, slowly and over the course of many months, a monumental hydroelectric machine for which no documentation can be found.

The site is soon renamed Machine Bay – and excavations continue for more than a decade.

[Images: A postcard featuring the Santa Cruz Wave Motor; via John Haskey].

[Images: A postcard featuring the Santa Cruz Wave Motor; via John Haskey].

In any case, the very real possibility of generating electrical power from the ocean is something I would absolutely love to see happen – and I would be particularly excited to see California, with its 100 years of research precedence, assume global leadership. As the Western Neighborhoods Project writes, “In California the idea of power from the ocean has been pursued since the 1870s. Experiments have taken place as far south as Imperial Beach near the Mexico border and as far north as Trinidad, in Humboldt County.” And, today, interest in wave-generated electricity only seems to be gaining in strength.

For instance, gubernatorial candidate and San Francisco mayor Gavin Newsom has gone on record, in an op-ed for the Huffington Post, writing that we should “power America with ocean energy.” He even cites the working landscapes of Adolph Sutro; Sutro, San Francisco’s 24th mayor, “recognized the power of San Francisco’s waves,” Newsom writes, “building a wave catch-basin that he hoped to one day turn into a wave-powered ‘overtopping’ system near Cliff House.”

But Newsom also seems to be cultivating a vision in which San Francisco assumes a new position of centrality in the national debate over energy independence – and it would all be based in tides. He writes:

Today in San Francisco, we’re not just talking about ocean power, we are advancing its actual implementation. We have submitted an application to the federal government to develop an underwater wave project off San Francisco’s Ocean Beach that could generate between 30MW and 100MW of power. And we are actively working to develop a tidal power demonstration project in the San Francisco Bay that demonstrates the promise of technologies that capture tides.

I’m all for this, frankly. As Alex Trevi suggests in his post San Francisco As It Will Be (a response to the climage-change-inspired Bay Area design competition Rising Tides), there is an extraordinary amount of machinic innovation to be found in reimagining the region’s hydrology (from Trevi’s “Golden Gate Dam” to his idea for mobile sewers).

[Images: Via the Western Neighborhoods Project].

[Images: Via the Western Neighborhoods Project].

In fact, the very idea that, somewhere over the hills to the west of us here in San Francisco, there is a sequence of machines plugged into the oceanic itself, is extraordinarily inspiring.

In the process, the dynamic hydroelectric capacity of the sea – if it could replace inland, coal-burning power plants – would revolutionize the geography of power generation in the United States.

Could San Francisco be the next Houston?

Who knows – but a new landscape of electrical substations harvesting gigawatts of coastal electricity from the shores of California, and then delivering it to the Rocky Mountains and beyond, would not only be a more “sustainable” future for power generation, it would be a technologically amazing feat that verges on Romanticism, plugging directly into the elemental.

I could open my own power plant, the BLDGBLOG SeaBattery™, available on the microscale.

[Image: Antonio Sant’Elia‘s hydroelectric-like vision of a Città Nuova; now imagine the Los Angeles River redesigned by Sant’Elia…].

[Image: Antonio Sant’Elia‘s hydroelectric-like vision of a Città Nuova; now imagine the Los Angeles River redesigned by Sant’Elia…].

So while the idea of an architect-designed national power grid – for instance, OMA’s plan for a European wind farm – is easy to ridicule as being frivolous, superficial, and distracting, I find it nonetheless quite brilliant to wonder what Antonio Sant’Elia, for instance, might do with a massive Pacific Wave Motor Complex looming somewhere on the coast of Los Angeles or out on some isolated cliffside near Santa Cruz.

After all, if architectural design can make people excited about, and financially interested in, future energy sources, then isn’t the comparatively small extra expense of getting an architect to design pieces of that future landscape worthwhile? One needn’t claim that infrastructure will save the architectural profession – it won’t – while pointing out, unironically, that wave motors are fun to sketch.

I would personally be quite happy to see stylized tide machines take shape in the sea – future archaeological presences there amongst rocks and hills, lost in fog one morning only to reappear at sunset against a backdrop of cresting waves.

[Image: Sant’Elia’s Città Nuova; alternatively, imagine a future Hydroelectric Monastery designed by Peter Zumthor in which monks of water live surrounded by technical equipment, timing their valves with tides, calculating lunar wave algorithms, opening silent gates at night while the rest of the world sleeps].

[Image: Sant’Elia’s Città Nuova; alternatively, imagine a future Hydroelectric Monastery designed by Peter Zumthor in which monks of water live surrounded by technical equipment, timing their valves with tides, calculating lunar wave algorithms, opening silent gates at night while the rest of the world sleeps].

Until then (if such a day comes), detailed exploration of these derelict motors left corroding in the sand – remnant machinescapes of artificial holes and tide pools, amongst the drowned foundations of forgotten piers – absolutely must continue.

At the very least, I can see an incredible Pamphlet Architecture produced about these lost mechanisms, with sketches and photographs, maps and stratigraphic diagrams in which inexplicable machines appear, several feet below ground.

A Graham Foundation-funded cartography of abandoned coastal machines hidden in the sands of premodern California.

It all seems straightforward enough: we could start that archaeology now – while planning more of such installations for the future.

(Thanks to Alexis Madrigal for the tip!)

Right now, I’m pitching a TV show about the book, basically so that we can get some resources to exhume the Manhattan Beach wave motor. Pull it dripping from the depths into the California sunshine.

The Sutro baths are such a ridiculous, beautiful project. Only in the era of the Panama Canal.

Wow, that’s great. I know there’s a tidal barrage to channel the tides near St. Malo, but I gather it just looks like a big pile of dirt.

My favorite spooky take on this was from the 20s or 30s. Haldane, the biologist Marxist felt that tidal power was the wave of the future, and that someday, after we had evolved humans to colonize all the planets, the earth’s rotation would have slowed so the moon would be in synchronous orbit, always staying at one place in the sky. Now that’s architecture.

Interesting article … it also happens to coincide with this news story about the new ‘anaconda’ that looks set to be introduced in the UK. I like the idea of these things being deployed in groups, like some kind of energy generating artificial family

Anaconda Wave Machine on BBC News

I am honoured to officially invite you to participate “The Eleventh Banquet of Iran Architectural Blogs” with the topic of “Professional Ethics in Architecture and Urbanism”, and will be grateful if you can send me your thoughts/comments/papers (about topic) as links until this month to this address: hesameshghi@hotmail.com

Hope to see you soon in the 11th symposium!

With warm regards.

Hesam Eshghi Sanati

http://www.hesameshghi.persianblog.ir

Dynamic fluid — a monster wave in super-slow-motion.

An architect, Yusuke Obuchi, proposed a similar wave machine that was published in 306090, and exhibited at the Storefront for Art & Architecture in New York in 2001.

I was searching through your otherwise very interesting post for what are the arguments against the use of tidal energy, but couldn’t find it (I might have missed it, I’m so tired), so here are a few reasons:

http://www.tidalelectric.com/History.htm

and for Kaleberg:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Rance_tidal_power_plant.JPG

Speaking of marine New Babylons:

http://www.nytimes.com/2009/05/13/business/global/13ship.html

So much space, just sitting empty and idle off the coasts of the world’s major port cities…

Awesome links – and I love the spatial possibilities in that empty ships story, C Neal. Thanks!