For his final student project presented last month at Rice University, Viktor Ramos produced The Continuous Enclave: Strategies in Bypass Urbanism.

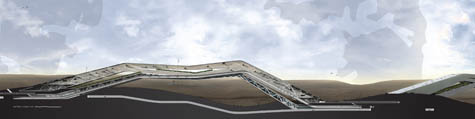

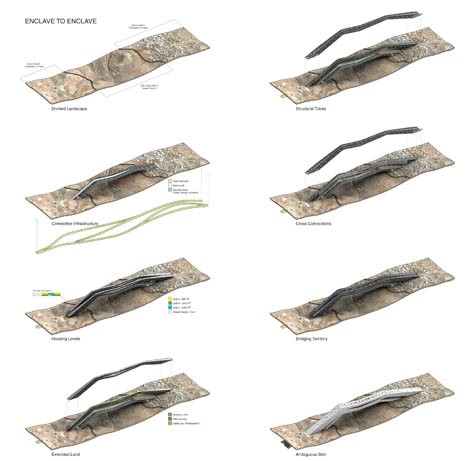

[Image: From The Continuous Enclave: Strategies in Bypass Urbanism by Viktor Ramos; view larger].

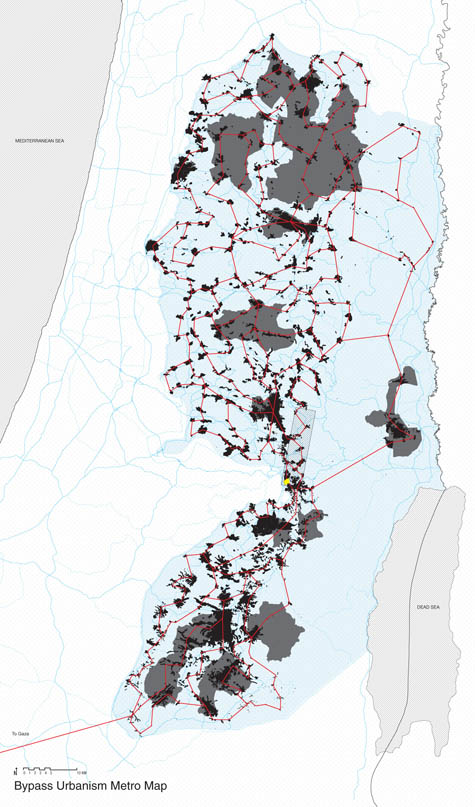

[Image: From The Continuous Enclave: Strategies in Bypass Urbanism by Viktor Ramos; view larger].

The project explores how new forms of habitable infrastructure might be extrapolated from a geopolitical agreement – in this case, materializing architectural form from the legal interstices of the Oslo Accords.

The result is a fantastic example of architectural speculation: genuinely massive – and impossibly cantilevered – bridges used as transport links, aerial housing, and skyborne agricultural complexes, all in one.

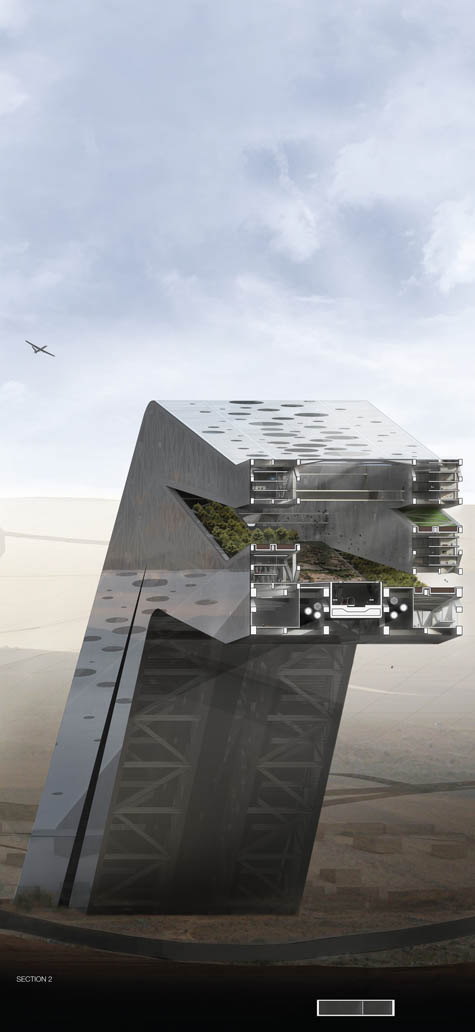

[Image: From The Continuous Enclave: Strategies in Bypass Urbanism by Viktor Ramos].

[Image: From The Continuous Enclave: Strategies in Bypass Urbanism by Viktor Ramos].

While clearly defying security protocols, as the “continuous enclave” and its network of bridges cross through sovereign Israeli airspace, these structures would link the dispersed islands of infrastructurally underserved territory now under Palestinian control.

From Ramos’s own project description:

This thesis takes a formal approach to understanding the Israeli-Palestinian conflict by studying mechanisms of control within the West Bank. The occupation of the West Bank has had tremendous effects on the urban fabric of the region because it operates spatially. Through the conflict, new ways of imagining territory have been needed to multiply a single sovereign territory into many. It is only through the overlapping of two separate political geographies that they are able to inhabit the same landscape.

One might say that these bridges present us with the staple as geopolitical form.

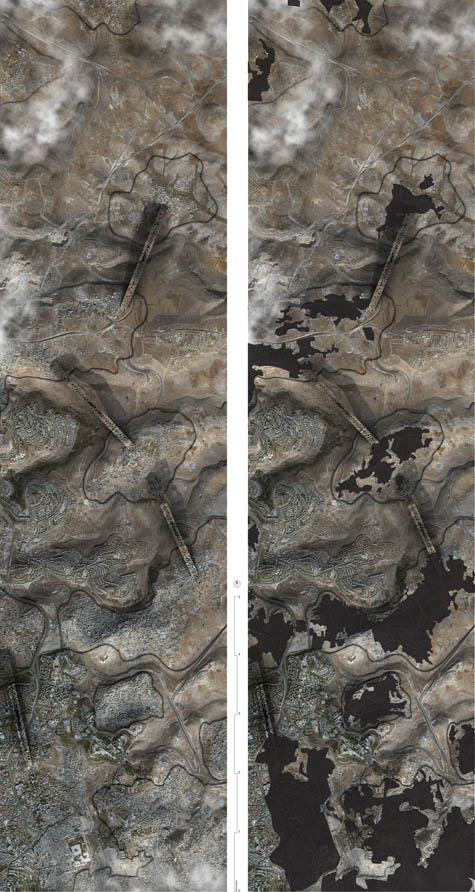

[Image: From The Continuous Enclave: Strategies in Bypass Urbanism by Viktor Ramos; view poster-sized].

[Image: From The Continuous Enclave: Strategies in Bypass Urbanism by Viktor Ramos; view poster-sized].

“The Oslo Accords,” Ramos continues, “have been integral to this process of division.”

By defining various control regimes, the Accords have created a fragmented landscape of isolated Palestinian enclaves and Israeli settlements. The intertwined nature of these fragments makes it impossible to divide the two states easily. By connecting the fragments through a series of under- and overpasses, the border between the two states has shifted vertically.

In the following cross-section, you can see the internal stacking of the space – an inhabited borderzone that weaves through the lower atmosphere.

[Image: From The Continuous Enclave: Strategies in Bypass Urbanism by Viktor Ramos; view larger].

[Image: From The Continuous Enclave: Strategies in Bypass Urbanism by Viktor Ramos; view larger].

To my mind, the project avoids the most obvious and expected pitfall of such an approach – which would be to suggest, naively, that architecture can, in and of itself, lead to a more thorough and lasting peace in the region, as if the entirety of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict would be eradicated if only they had better architecture.

Ramos instead uses the Oslo Accords as a kind of spatial source-code from which unanticipated structural forms might be extracted.

For those of you who have read Delirious New York, it’s as if the Oslo Accords have been turned into a geopolitically active 1916 Zoning Law. That law, of course, established spatial guidelines – for instance, enforcing setbacks for buildings, leading to an era in which skyscrapers rose up like ever-narrowing ziggurats – from which the buildings of Manhattan would then be shaped.

As Koolhaas himself writes, in the wake of the Zoning Law architects would “have to carve the final Manhattan archetype from the invisible rock of its zoning envelope in a campaign of specification.”

In Ramos’s project, that “invisible rock” consists of disputed territorial claims hovering virtually over the geography of the West Bank. The distinct new form of spatiality “carved” from that rock is the bypass.

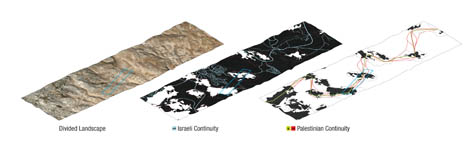

[Image: From The Continuous Enclave: Strategies in Bypass Urbanism by Viktor Ramos; definitely view larger].

[Image: From The Continuous Enclave: Strategies in Bypass Urbanism by Viktor Ramos; definitely view larger].

Again, from the project description:

One feature of the Oslo Accords is the bypass road which links Israeli settlements to Israel, bypassing Palestinian areas in the process. These are essential to the freedom of movement for the settlers within the Occupied Territories. Extrapolating on the bypass, this thesis explores the ramifications of a continuous infrastructural network linking the fragmented landscape of Palestinian enclaves. In the process, a continuous form of urbanization has been developed to allow for the growth and expansion of the Palestinian state. Ultimately, this thesis questions the potential absurdity of partition strategies within the West Bank and Gaza Strip by attempting to realize them.

Thus creating what Ramos calls bypass urbanism, or a self-connected maze of new territories in the sky.

[Image: From The Continuous Enclave: Strategies in Bypass Urbanism by Viktor Ramos; view much larger: top, bottom].

[Image: From The Continuous Enclave: Strategies in Bypass Urbanism by Viktor Ramos; view much larger: top, bottom].

There are any number of other directions such a project could go, but I’m particularly excited by the idea of applying this same sort of analysis to other conflict zones, elsewhere, all over the world.

Of course, the precedents for this are many. After all, what is the Berlin Wall but a piece of architecture pulled from the dreamscape of international legal infrastructure?

In fact, I’m reminded here of Rupert Thomson’s under-appreciated recent novel Divided Kingdom – especially because the basic premise of that book was at least partially inspired by Rem Koolhaas’s own student thesis project, Exodus, or The Voluntary Prisoners of Architecture. As Koolhaas wrote:

Once, a city was divided in two parts. One part became the Good Half, the other part the Bad Half. The inhabitants of the Bad Half began to flock to the good part of the divided city, rapidly swelling into an urban exodus. If this situation had been allowed to continue forever, the population of the Good Half would have doubled, while the Bad Half would have turned into a ghost town. After all attempts to interrupt this undesirable migration had failed, the authorities of the bad part made desperate and savage use of architecture: they built a wall around the good part of the city, making it completely inaccessible to their subjects.

The Wall was a masterpiece.

The U.S.–Mexico border would seem an obvious place for any investigation of “bypass urbanism” to begin; just today, the New York Times looked at the decaying after-effects of the Dayton Accords and their spatio-sovereign impact on the future of Bosnia; and Lebbeus Woods has long explored the architectural effects of political separation, from Paris and Berlin to Israel and Sarajevo, seeking out those fissures wherein geopolitics exhibits its own peculiar form of spatial tectonics.

But what new kinds of space might we yet extract from territorial agreements between, say, India and Pakistan over Kashmir, or Turkey and Greece over Nicosia – or, for that matter, what strange infrastructures might we build in Baarle-Hertog, what pavilions inspired by the Akwizgran Discrepancy, and how might most interestingly extract architecture from the international date line?

[Image: From The Continuous Enclave: Strategies in Bypass Urbanism by Viktor Ramos].

[Image: From The Continuous Enclave: Strategies in Bypass Urbanism by Viktor Ramos].

Even with so many precedents, it would seem, such studies have still barely begun.

You can see much, much larger versions of all of these images in this Flickr set: The Continuous Enclave: Strategies in Bypass Urbanism. They are incredibly detailed and well worth exploring in full!

(Viktor Ramos’s Continuous Enclave was produced at Rice University. It was advised by Troy Schaum under the direction of Fares el-Dahdah and Eva Franch, with additional input from John Casbarian and Albert Pope).

Very interesting project, mixing a bit of sci-fi in the aesthetic. With the way the conflict in the region is going you could almost believe this would happen.

Two comments…

1) re: section drawing: Sandworms!

2) re: sandworms: Why restrict bypass routes to the lower atmosphere, when the lithosphere is available too — go underground as well as over. (This seems especially obvious since there’s already a network of frontier-crossing tunnels in place in parts of this territory, although they’re expressed in a more vernacular, entrepreneurial idiom these days…)

Megastructures like these, while fascinating, cast enormous shadows, both figuratively and literally (as you elude to in your description of Manhattan skyscrapers).

I see the literal shadow as a method for further marginalization and control: design your structure so that certain areas never get any sun and you will have subdued entire populations, who would then need to supplicate not just for food and peace, but for access to sunshine.

What a horrendously dark vision!

I sincerely hope that the images are intended only to point out the absurdities of borders and attempts at dividing people. It is troubling if we are expected to imagine this as some sort of viable solution to the conflict.

Should this be accepted merely as an analytical exercise? Or does it represent the authors total absence of critical self-judgment in pursuit of some hollywoodish fluff?

If this how our youngest and brightest envision the future, we are surely in trouble. The professors should really step in and give this student some guidance.

Even if this proposal seeks only to “question the potential absurdity of partition”, the images represent an ominously dark vision. It is apparent that great care, and dare I say passion, has gone into crafting this misguided gloominess. This sort of sensibility bleeds naturally into the fashionably slick brutalism that ignores the users of buildings – people. Students can at times forget fundamental human needs and fantasize about spaces that only Darth Vader would feel comfortable in.

Projects such as this demand us to question the authors true motivation. They need to be called out for what they are.

This project seems to really question the nature of architectural representation. Typically, architects create images intended to sell an idea; beautiful images that encourage you to accept the ideas within the project to see it realized. This project seems to use it very differently: architectural representation used not to sell a building or encourage its construction, but instead perhaps to discourage it. To make us really question what is taking place here. To recoil from what it offers. Maybe its gloomy, but can it be any gloomier than the facts on the ground?

It is important to note that not all architectural proposals are made in order to be built.

haha. If the Palestinians had money, you can be sure Hadid would offer a vision like this…beautifully photoshopped building/bridges where the palestinians can piss, shit, throw shoes and drop other bombs on the homes and businesses of Jews. I love it, totally absurd, totally fantastic, utterly implausible and unrealistic, coupled with amazingly realistic renderings. And the building forms looks really familiar! Good sense of humour! A+ Give him his degree!!

Anonymous, the thesis statement itself includes this line: “Ultimately, this thesis questions the potential absurdity of partition strategies within the West Bank and Gaza Strip by attempting to realize them.” So when you say that you “sincerely hope that the images are intended only to point out the absurdities of borders and attempts at dividing people,” you can feel assured that that was very much a part of the project!

This project reminds me of Superstudio’s continuous monument. It also looks like a larger piece from a second year studio project Viktor did located around White Sands,NM. The smaller tower looked almost exactly like the cross section image, sticking out of the sand and could swivel around. Maybe it was really the escape route from the US-Mexican border.

For my part, I’m reminded of Syd Mead’s megastructures such as this:

http://www.ljplus.ru/img4/s/u/su30/fat-SydMead-Megastructure.jpg

Hellish. Unrepentantly awful. The mind reels. Does the student hate cities? Or has he simply never seen one?

And another thing… You have so much time in your education you can afford to waste studios on ironic “just kidding” work? It turns out design is hard… maybe work on that, and leave the commentary to folks who work at “Commentary”.

Anonymous, would you ask George Orwell, for instance, after he wrote 1984, whether or not the premise of his novel “ignores the users of buildings—people”? The bizarre insistence that anything resembling an architecture drawing has to be buildable, and that it can’t be a space “that only Darth Vader would feel comfortable in,” seems to be the last gasp of a totally different generation. Do you demand the same of cinema, literature, and poetry? Why must architectural design be limited to the utilitarian? For every post on BLDGBLOG, there’s a Southern Revival Home Depot somewhere doing its job just fine.

Why are all you angry people with no imagination reading BLDGBLOG in the first place?

Life and politics are brutal. What is the point of design if we can’t dream and speculate?

to the previous anonymous: I’d love to see some of your design work, as it seems you yourself are able to afford the time spent on your own commentary . . .

Arjen said:

I don’t get the excitement. It may be stylish, but in essence this is Jerusalem: multi-layer corridor urbanity. The moment you transplant this reality to the world of enclaves and colonies it looks brutal, but it is the same. Only the roles (Jews/Palestinians) have been reversed here.

Geoff, you are missing my point – it’s not about buildability or utilitarianism. It’s about sensibility, intention and motivation. There is nothing constructive about these images. What good do they do? If I am an Israeli or Palestinian how does this exercise help me? What do we as a society gain from this nightmarish masturbation?

I continue to question the stylistic expression and the conscious decisions (motivation) of the author in arriving at these forms. I think it is fair to question someone on these grounds, as in the authors own words: “This thesis takes a formal approach to understanding the Israeli-Palestinian conflict by studying mechanisms of control within the West Bank.”

The scheme offers a horrendously dark scenario that does nothing to progress the situation or help the people who are suffering daily. That someone would use the conflict to create pointless eye candy is offensive on so many levels.

-Anon (2/24 12:08, 12:59)

Ps. Don’t get me started on Home Depot and the big box franchise disease that is continuing to gut this country from the inside out. Oh, and I adore speculation and fantasy – it is vital to keeping architecture relevant, that’s why I read your blog!

Too many trolls posting comments on bldgblog these days

Well, trolls traditionally live underneath bridges…

the name “continuous enclave” immediately made me think of superstudio’s continuous monument as c.m. noted above. all in all i think ramos’ work is an interesting venture pointing out the absurd results of the oslo accords. i guess what continuous enclave lacks and what made superstudio’s continuous monument really poignant was a reasoning behind the building form. superstudio really explored the concept of the box and what it represented to philosophers like wittgenstein. they utilized the box form and manipulated it through relentless repetition to create the ever provocative continuous monument. what viktor ramos’ project lacks is that link between form and meaning. he did a great job and i love the fact that he tried to tackle this issue. ultimately however, it really does look like a zaha hadid building and i’m not sure why he chose that form, beyond the fact that he was obviously well trained in digital design.

-nicolas

what a project!! i think any notion of any architecture being only for the “good” of humankind needs to be dumped. some architect must’ve designed concentration camps too right?

and to give you the other extreme of strange opinions, the only thing someone might have to say about the project is ‘wow this guy should be paid millions JUST for the renderings!’atleast people are expressing some kind of valid (if unusual) thoughts… that is enough to ensure the future of architecture as a profession is safe.

Imagery is fantastic, I can picture myself entering a virtual world with my game controller ready for action.

1984 was obviously a didactic message, the probability of the scenario wasn’t meant to be confused with its desirability, Superstudio I think qualified their speculations with a bit of irony by detourning images of dumb contentment. This critique whilst visually impressive seems to be a bit humourless and lacking that bit of reflexivity that tells you which way this is going, taken on images alone no one can tell if this is meant to be desirable, totalitarian, grotesque and the ambiguity of intentions is indistinguishable from ignorance of these readings ie there doesn’t seem much room for benefit of the doubt, unless the blurb is meant to redeem it (but then why bother with building?). In fact the deeply instrumental character of the scheme makes it no different from any other crazily shaped speculative scheme for offices or condos in China, Khazahkstan, Dubai, or any even scheme from OMA, MVRDV etc. is this then meant to be a critique of architecture? No one can tell. If all it takes to critique a situation is to swap out the ground plane from any piece of 21st century performative diagram and replace it with the latest google aerial photo of geopolitical contention is it really critique?

The only more relevant thesis would have been to design a building that would solve the problem of our global economic meltdown. I find it just fascinating how people get wrapped up so much in what it looks like and how it’s rendered; they seem to be missing the point. The student made an effort to use architecture as a means of solving a political problem. In the world today, is this not worthy of praise? While the notion that architecture can save the world is not new, I wish more students had a broad enough world-view to be tackling issues like this and were using architectural concepts to approach them. The ambiguity regarding its intended “message” (if there is one) should be praised as well, because such openness is virtually impossible to acheive once one becomes a “real architect”. Are you all so old and jaded that you don’t remember being in a studio?

http://www.evolo-arch.com/cskyh.html

urban bypass applied at city scale

I really like it. I can imagine what it would be like to live in something like this. Obviously there are lots of practical concerns, but this isn’t exactly a practical proposition.

as an israeli that is not ashamed to dream, and as an architect, i found this project highly disturbing, on three levels. in the thesis level – instead of finding a real solution, it captures the problem in a fascistic mega-structure. in the last years Israel has built a long concrete wall to separate those territories from Israel to avoid bombings and such. although it dramatically increased security in Israel, it created a huge damage to the fabric of Palestinian AND Israeli life in those areas, and is considered one of the most controversial projects ever built and by many people across the world it’s considered on the brink of crime. this project, in my opinion, does exactly the same damage. furthermore – in the architectural level – those megastructures proved themselves worldwide to be wrong. the amount of ecological damage such a building will create is enormous. think of the land below it – would you want to live there? come to think of it – would you want to live above, in the structure itself? and last – on the practical level (although many times neglected in the academy) – urban tissue can’t exist in the air – it is connected to the ground with a huge amount of infrastructure. and what about cars and other modes of transportation? i see the practical side of architecture as an un-neglectable part of it, and a part that makes it much more fascinating than, let’s say, just sculpturing.

i think it’s a very sad project, and i think the images demonstrated it well…

It’s refreshing to read critiques of this project such as that from Nicolas: “i guess what continuous enclave lacks and what made superstudio’s continuous monument really poignant was a reasoning behind the building form. superstudio really explored the concept of the box and what it represented to philosophers like wittgenstein. they utilized the box form and manipulated it through relentless repetition to create the ever provocative continuous monument. what viktor ramos’ project lacks is that link between form and meaning… it really does look like a zaha hadid building and i’m not sure why he chose that form…”

Or muthacourage’s point that “the deeply instrumental character of the scheme makes it no different from any other crazily shaped speculative scheme for offices or condos in China, Khazahkstan, Dubai, or any even scheme from OMA, MVRDV etc.”

Meaning, in both cases, that if you take away the project’s accompanying text, then all you have is a Zaha Hadidian form in the desert – and it could be a shopping mall, a UN complex for refugees, a police checkpoint, or even a business center for Comcast.

Although, as The Unbuilt mentions, “The ambiguity regarding its intended ‘message’ (if there is one) should be praised as well, because such openness is virtually impossible to acheive once one becomes a ‘real architect’.” Which shouldn’t be overlooked.

But Nicolas and muthacourage present, in my opinion, totally valid critiques of the Continuous Enclave.

However, in many of these other comments, I find the idea that an image depicting architecture must be reacted to emotionally as if that image advocates what it depicts to be an absurdly limited approach. For instance, as anonymous writes, “If this how our youngest and brightest envision the future, we are surely in trouble.” But that mistakes drawing a picture for desiring what one draws – and it overlooks the more politically important point, which is that this future is not something “our youngest and brightest” seek to create, it is simply the future they are inheriting. To put it another way, if you design a military concentration camp at the north pole for climate change refugees in the year A.D. 2179, it should by no means be assumed that you are hoping this future comes to pass. You are simply illustrating what it might look like.

Because nowhere has this project, the Continuous Enclave, been presented as a desirable outcome of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict; it has simply been presented, at least in my understanding of the project, as a deliberately absurd spatialization of the unclear legal interstices opened up by the Oslo Accords. There are spatial implications inside these international agreements, and this project seeks simply to show us what those might look like. I don’t think I’m misreading the project; as Ramos writes: “Ultimately, this thesis questions the potential absurdity of partition strategies within the West Bank and Gaza Strip by attempting to realize them.”

But, yes, I think Nicolas, in particular, is exactly right with his critique. At the end of the day, why does this thing have to look like something designed by Zaha Hadid? Why doesn’t the project interrogate its own form more deeply?

The idea, though, that we have to react to images of unbuilt architecture by assuming someone actually wants to see them built strikes me literally as a waste of time. Anonymous asks: “You have so much time in your education you can afford to waste studios on ironic ‘just kidding’ work?” But take this question out of its context in architectural design and apply it to, say, writing; in that case, anonymous would be there hurling invectives at novelists, demanding that they get back to writing real history books, as if we only write fiction because we are self-indulgent and have spare time on our hands. Or as if fiction, story-telling, and imagined worlds have no practical use in helping us to understand our circumstances differently. Those are “‘just kidding’ works,” according to anonymous. All of myth, poetry, art, cinema, and literature has been dismissed by anonymous’s absurd and vacuous remark.

But producing an image of something in no way means that you are advocating what you depict. Do you watch Minority Report and walk away stunned, thinking: Why on earth does Steven Spielberg want us to live like that…? Or you read Brave New World: Why does Huxley have such a dark vision of the future? It’s just not helpful… If that isn’t how you react to film and literature, then why – and this is a genuine question – why would you look at these images here and think: Why in the world does this guy want Israel to be rebuilt like this…?

Finally, then, another anonymous – so much anonymity! – writes that this project “offers a horrendously dark scenario that does nothing to progress the situation or help the people who are suffering daily.” But, again, this seems short-sighted to me. The project, in fact, accomplishes something quite helpful – and useful, not to mention extremely interesting – which is that it explores how political agreements and territorial treaties have, within them, unrealized spatialities that we would do well to explore. In this exact case, I will agree that the results look like the opening scenes of a Tony Scott film, but that doesn’t invalidate this approach elsewhere, for others, and it shouldn’t be dismissed out of hand because it doesn’t offer immediate, impatient relief.

Geoff,

Hear Hear, Thanks so much for your last comment and synthesis of the previous comments (anonymous and otherwise) as it is always heartening to be able to read and respond to images AND to be able to engage in discussions and debates on meanings and interpretations. That is what you seem to have been promoting in your blog since the inception. Keep up the great work and stimulate us all to strive for a better design and improved environmental awareness.

Hi Geoff,

Just wondered if you were aware: Rem Koolhaas said in an interview with Charlie Rose that the solution to the Gaza conflict was a total re-imagining of two-dimensional borders. He argued for a complex three-dimensional form, as has now been shown above.

(I would send a youtube link, but I just looked and they’ve all been removed. I think it was back in 2005)

Best, Charlie

I think it is interesting to propose a plan that ‘solves’ the simultaneous claim to this land.

a similar idea is here:

http://westbankspiralplan.blogspot.com/

Thanks, Douglas, for the comment! I don’t know that BLDGBLOG always lives up to that promise, on the other hand (and I know many people who would say that it does not ever do so!) but I do hope that the site can act as a host for interesting discussions that might not occur so easily elsewhere.

Charlie, I had missed that, actually – very interesting. I’ll look it up. However, that also has the effect of making me even more curious to hear how Lu, the commenter from above, came to his or her opinions about this project and my interpretation of it (including the throw-away line: “there’s absolutely nothing in common with the projects of koolhaas”).

I’m aware of how (over) identifying with a logic to its limits can reveal its absurdity, it’s an artistic strategy that’s served critique quite well for the past couple of decades, Atelier Van Lieshout do a pretty good job of updating it for a sort of mid 90s context I guess. But there’s a structured conflict to their ambiguity which stops it from being just unarticulated (unintended?) vagueness, the extraction of value and labour from people is done in something that amounts to a concentration camp and the polemical association with slaves is well polemical. There’s no conflict in this critique’s ambiguity and I don’t think Viktor can get away with unintended readings when you advance a project along politically polemical lines, that part just seems unthought through.

We could simply ask who is building these bypasses? Is it a gulag built by the Israeli’s or is it “the last hope” built by Palestinians? If we can take legalese as the starting point, why not consider something as equally important as the client? I was being harsh before, and it’s interesting to consider the surplus value embodied in the legality of the border (why stop at airspace? would excavating that part of the agreement add to the physical contortion (and symbolic absurdity) of these bypasses?), I just wish this project had followed that side of it through before running the diagrammatic algorithms – which you can otherwise find in any project. Critical speculation and thoughtful ambiguity is important, but it has to have a bit of rigour otherwise architects are just playing dillitente again with a new vocabulary.

Thanks for replying Geoff, I enjoy the blog, keep it up!

I like how it references the tunnels that already function to sustain Gaza through an economy of smuggling.

A reader named Luis Pieraldi has sent in a link to a project of his own, that sought to “to deal with the reality of the checkpoints and the Separation Wall” between Israel and the West Bank. “My site was a fragment of the Wall in the Qalandia Checkpoint between Jerusalem and Ramallah,” Pieraldi explains. “The main concept was to create dialogism between one side and another and between military and humanitarian/civil use. My strategy was to use the wall as a space, and when you enter it, you will have hints for where are you going but can’t go directly since you have to go thru security. In the project you have various instances where you can feel you are in one of either side. The view for Palestinians to Jerusalem is always thru a screen as a nostalgic view representing the fragmented territory. My project doesn’t have a redemption objective; it deals with the reality of the place.”

Pieraldi adds that the project specifically includes:

-Military quarters

-District Coordination Office (for permits to enter to Israel)

-MachsomWatch (this group works in the checkpoints as mediators between Palestinian and the Israeli Defensive Forces)

-An indoor and outdoor market (the market exist around the checkpoints)

You can see images of the project here.

ok…this imaginative approach to an inherently difficult dilemma is to be applauded.Does anyone think the third sheep from the left has eyes that follow you, no matter what angle you observe the picture from?

Take a look at this picture: http://sytske.files.wordpress.com/2008/10/20081014_116.jpg

you know why those nets are there?

It’s because the Israeli that live above the Palestinians in Hebron THROW THEIR GARBAGE OUT THEIR WINDOWS ON THE PALESTINIAN STREETS!

So good luck with you plans..

In the West Bank some Israeli roads are build on top of Palestinians roads. If you consider this with the Israelis occupying the top levels in the old part of Hebron and the roads in the West Bank that are exclusive to Israelis you will know that the concepts Viktor are applying aren’t radical, nor new, they just happened under Israeli control, and he acknowledges it just like that.

If you quit the “West Bank is only for Palestinians and Jerusalem is their capital” approach, this project is helping the Palestinians. The land that remains under this structures could be the no man land that is created in borders under conflict and trenches. Both sides should have bypasses and villages, so they don’t have to deal with each other.

Radical right?? Thats what happening today!!

easy RPG targets…. science fiction only i guess…

new babylon in palestine. what a great idea. beautiful, inspiring project.

LOL@ all the people who cannot bring them selves to see an architectural concept as anything more than a literal translation. Of course this will never get built. Of course the designer knows it will never get built. As a form of art and abstraction of non architectural ideas and concepts, architecture as a theory is just as much a social commentary medium as it is a function structure. I think the suggested reading on this one occurs between the lines…

Sorry bro, this is not how architecture can make the world a better place in my oponion.

Localise the problem, although who knows if the issues between Palestine and Israel.

Liam

Peace

Sorry bro, this is not how architecture can make the world a better place in my oponion.

Localise the problem, although who knows if the issues between Palestine and Israel will ever be resolved?

Liam

Peace

oh no — even more bs that usa taxpayers would have to pay for in that welfare wasteland? israel wouldnt exist w/o our tax money as it is, please no expensive ideas that would milk us even drier. or at least let the saudis or somebody else pay for it!

This reminds me of Walking Through Walls–

http://eipcp.net/transversal/0507/weizman/en

–only related by tangent in that the way warfare is being conducted in the region is becoming increasingly independent of the existing lay of the land and especially the constructs built upon it. You could say modern warfare has the very real capability of rendering even grandiose restructuring of physical space (in the name of peace), at its mildest, less effective.

The whole “Walking Through Walls” discussion bears fascinating concepts and I’m curious to hear your thoughts on the military’s embrace of playing the role of “operational architects”, etc.

Hello Geoff,

As an architect, I thought a lot about Victor Ramos project. I followed the discussion which has been going on because it made me think strongly about own visit in the occupied territories within own experiences in my architectural thesis which dealt with the analysis of portable housing units in the West Bank… You might know Professor Wes Janz from Ball Stat University who was my thesis advisor and who taught and made me think a lot about human, social and political aspects of architecture and the built environment…

In this discussion about Ramos’ thesis I see limits of architectural design and the value of architectural analysis, in which the role of the architect’s need to find his/ her own role.

Ramos’ thesis explored parts of the Westbank’s spatial situation with a design vision of how inhabitable space within two overlapping spatial legacies found in this landscape can look like.

Ramos came out with astonishing design approaches, architectural impressive, really fantastic and fascinating gestures with multi-levelled habitable spaces. As Eyal Weizmann explained, the landscape became a vertically divided space. As such Ramos created multi-levelled and multi-zoned spaces for housing, access/ traffic and agriculture. One might continue these spatial functions and produce vertically oriented buildings, bridges or other ‘buildings in the sky’ as you want and need.

From an aesthetic standpoint, Ramos’ architectural language is fascinating which resulted out of the given legal situations which in turn was negotiated in peace processes and agreed accords. The formal aspects of the design is formidable, well-articulated, professionally presented with well-detailed renderings. The atmosphere even reflects some sort of coolness, cool earnestness. Because I studied the space in the occupied territories and the ‘sandwich-like’ spatial order in this territory I exactly knew what the designer intended to do: he himself was fascinated and challenged to think about new forms of buildings within a complex given volume…

Nevertheless, Ramos’ ideas are not really new for those who actually live in the West Bank: the reality there is loaded by enemies who are forced to use overpasses and underpasses as seen in Gilo; the Old City of Hebron has the best example for multi-layered/ vertical housing situations wherein Jews live above Palestinians, who themselves built wired roofs to protect themselves from ‘falling’ objects and acid liquids; those both people over there need to lead there lives everyday in enclaves trying to hold on to ‘continuity’ and normality by using meander-formed roads and pathways designated to only one of those two peoples…

THEN, what is the point of Ramos’ thesis? Only to think about JUST how to make better architecture within this grotesque spatial environment? It is puzzling to see these visionary images of ‘large scale gestures’ believed as being ‘better’ architecture, a better place to live in, but neglect totally the human, social and political aspects… How can an architect make design proposals for a political, contested undefined space while ignoring his/ her own political contribution to this context?

What is the context? Ramos misses to point out the contextual conditions separately from his design aim. The context is a conflict-place in which its counterparts are NOT of equal rights and power! This landscape is not the result of the negotiations of two equal parties trying to create the most possible space within a small two-dimensional piece of land and its volume for as many people as possible who want to have an extraordinary architecturally exciting space to live in. (I agree that this is an intriguingly attractive assignment for architects!!!) But this is a landscape of a powerful, institutional and legalizing occupying power over another weaker but resistant and terrorizing other people; both people are suffer in undignified living conditions. And, this landscape is an ‘apart’ landscape wherein people are assigned not only to oppositional and antagonized people but also to different streets, ways, settlements, resources and for different rights.

What about the people? The Palestinians suffer disgraceful and strongly by the occupation of another nation which divided all the landscape into separated, densely over-populated enclaves. They cannot go to from A to B without a huge time delay, being afraid of being late for the exams or even giving birth to children at the check-points because the guardians closed down transition nods… On the other hand, the settlers are raising their children voluntarily or involuntarily within subsidized hilltop settlements. They live within a political overheated atmosphere, guarding and overseeing the freshly claimed territories and their neighbours within their simple and badly built caravans, which sometimes topple down from the mountain top when the hard winds. They are both guardians and prisoners in their own settlements, objectified to military tools for the political large game. In this panoptical context, in this kind of a produced space, all individuals are made fearful, aggressive and manipulative thus uncompromising for any peace talks…

It is an inhuman landscape, a brutal and vicious part of a built environmental example, wherein political opponents took material and physical positions built in concrete, sometimes permanent sometimes temporary positions but with strong territorial interests so obvious within everybody’s everyday life…

The main question is: in this context of power over space and territory and its spatial outgrowth, what can be the role of an architect?

Did Ramos ask this to himself? Now, by choosing the context and making a design proposal for the found situation he made a decision. Thinking only in design terms the architect plays into the hands of one interest group: Ramos strengthened the power that occupies and keeps these found complexities of 3-dimensional spatiality alive.

Is that what the role of architects should be? Only because architects are able to think about inhabitable space even within complex systems, is this what our profession should do? Should architects be only server for all kinds of landscapes even for the most contested one? As Ramos choose to do, should be formal aspects are brought to its heights to make ‘inhabitable space for everybody’ while ignoring the real needs of a real peace in this region of the world?

Maybe he should have chosen NOT to design within this context! Why architects need to design always? Yes, Ramos could have chosen a more design-passive but a politically-active position by NOT putting up a design scheme but a spatial analysis. This would have been more visionary in terms of the role of architects and architectural ethics and architectural practice. And the reason is simple: architects are able to understand spatial circumstances even without doing a design proposal!

Ramos DID NOT chose this line of spatial analysis thought, but used – let me say traditional design thought – by outpouring large scale, monumental ‘big A – Architecture,’ in which the humans almost are hard to find! His statement of “ultimately, this thesis questions the potential absurdity of partition strategies within the West Bank and Gaza Strip by attempting to realize them Ultimately, this thesis questions the potential absurdity of partition strategies within the West Bank and Gaza Strip by attempting to realize them” is zeroed by his choice to make a design proposal. (To understanding the spatial absurdity in the West Bank you could have researched just small-scale architecture such as mass-produced transportable caravans used in strategically positioned clusters. For that, architects are even not of use!)

I think that an architect needs to be more than somebody who designs and creates spaces and make them inhabitable just for the sake of visionary, design terms… Architecture should be much more about awareness and responsibility because spatiality has many effects on human everyday life and society which is not always understood by everybody… As a result, architectural design cannot be the solution for the Israeli-Palestinian conflict as Geoff mentioned, but a tool to strengthen and exaggerate existing circumstances! Whereas architectural analysis can be a sincere tool for understanding one region’s political and spatial absurdity… It is a great tool to expose the spatial affects of the political negotiations and the power of its parties… It is also a great and potential, alternative for architectural practice!

I guess it would be worth to spend a phd analyzing conflicts in their spatial dimensions… Geoff, you gave some interesting amount of examples of architects dealing with and thinking about the connection between buildings and war zones…

If anyone is interested in analyzing the power of small-scale, portable buildings in the West-Bank, here are 2 links:

http://onesmallprojectwiki.pbwiki.com/Houses%253A-Portable%253A-West-Bank

http://www.polarinertia.com/july05/israeli01.htm

Many greetings from Frankfurt/ Germany,

Tülay

In the ongoing mess that is the Israeli/Palestinian conflict, it is going to take “outside the box” thinking that so far has not been illuminated.

Ramos is to be commended for his extremely ambitious concepts. And has been mentioned here already, the multi-tiered mess that has become the West Bank in it’s current form is just not going to be a viable solution going forward for some 10 million Palestinians.

While lack of freedom of movement is most often sighted as the major drawback to a viable Palestinian state, the dilemma of water, demographic growth considerations and solutions for some 7 million refugees has no real hearing in anything that I read as being discussed or considered.

The current long term solution being seriously followed on both sides is a fantasy that the other side will just some how magically disappear. Or, truth be told, the extermination of the other side.

There is some give and take on both sides, but each keeps those few precious final stumbling blocks as deal breakers over and over again. And some that are actually very major long term concerns, the chief among them being the water division, scarcely get any mention at all.

I do agree in the end that is is a spacial problem. But in my thinking it is a spacial problem that is being too finely tuned to a few specific areas instead of a broader regional solution to a broader range of problems.

One can fight over this block or that alley in some West Bank village, but the solution is really to be found by backing up and taking a very hard look at the entire region.

Some things rarely discussed but cannot be ignored:

Israel will never settle for the thin strip of land along the sea mid country.

Palestine will have to have some part of Jerusalem and free access to all Arabs to the Temple Mount.

Palestine must be a viable country going forward.

Israel must feel that its borders are adjacent to countries which are at peace with the idea of their being a sovereign state.

The Golan should be settled to the agreement of all.

The ownership and use of water for the region must be determined for any settlement.

All of that relies on an understanding that the space now occupied by literally thousands of people will have to be rethought. And if both sides really want a solution then the number of people considered to be vested in one side or another have to step up and make their contributions.

I do not know what shape the final division of space will take. I just know that the solution will be in how the space is, in the end, divided.

Just some thoughts on division.

http://palestineroad35topeace.blogspot.com

Gary Tucker

Denver, USA

Tulay,

How can you say you’ve followed this discussion and then make the comment,

“THEN, what is the point of Ramos’ thesis? Only to think about JUST how to make better architecture within this grotesque spatial environment?”

???

You don’t even have to follow the discussion (it is mentioned in the project brief) to know that the project is not about a better place, but instead an absurd reality of what’s existing—in the same way that MVRDV’s Pig City uses architecture to reveal the absurdity of a consumptive society. (ie, MVRDV didn’t design Pig City with the intention to have it built.) In that regard the Continuous Enclave is contextual (spatially, not formally); it’s very much a spatial analysis of the situation that gets formalized through an urbanism that performs in a certain way—bypassing.

It’s not trying to be visionary in a utopian sense as you seem to be writing (that, of course, would be very traditional!) but paints a dystopic future for the present reality. It’s shocking. It’s suppose to be. Portable, mass-produced, caravan, housing unit cluster utopias (whew!) are a (to use your emphasis technique) COMPLETELY different project that are in no way relevant to what the Continuous Enclave as a project is about.

If nothing else, the Continuous Enclave is successful in its ability to create this whole discussion. (How many other entries have a comment string this long or this heated?) It’s a project that makes you take an opinion on not only the issues brought up but on the role of architecture today.

Good work, Vik!

Hello John,

I still question the way Victor Ramos presented his approach, because it makes the viewer being astonished by the architect’s large-scale architectural gestures and representation skills more and dazzles from humanitarian issues. (Not MVRDV: they keep their focused critique in an abstract, formal attitude which makes the project so plausible.)

What is the point of ‘painting’ (which he did really good) ‘a dystopic future for the present reality’ if not to put traditional architectural skills into foreground which is about high end formal articulation of self-created mega structures? Why designing and putting a lot of mind-thought into ‘impressive but horrible paintings’ of an inhabitable bridge construction; even though Victor saw at the end, that is was absurd? Why a building at all??

And as if architects are the only people who create, manipulate and understand spatiality. You can already notice in this particular context that with every stone, with every wall, with every house and with even such unsexy things like mass-produced caravans in the West Bank that there is already an absurd spatial game going on. Here, you can already find bypasses, overpasses, underpasses, bridges which transform to roads, to tunnels, to bridges again; there are multi-story buildings in whole streets which are nationally, religiously separated…

My point is that there are many approaches to understand spatiality and context. Surely, one might be the way Victor Ramos did go. But there are also other approaches to understand and explain spatial complexities which put formal aspects behind deep thoughts.

And yes, it is about the role of architects, being more often the passive designer, while becoming more the politically active spatial analyzer.

(See Tadashi Kawamata, Krzysztof Wodiczko, Roy Kozlovsky, Santiago Cirugeda Parejo, Eyal Weizman, Lebbeus Woods, Paul Virilio)

Aside from the already mentioned downsides to megastructures, I think a lot of people have overlooked some possible benefits of them in such a conflict. While it may seem foolish to put a lot of people into an easily attacked structure, the sheer size and amount of civilians inside gives it a kind of security from the aggression of a nation-state. Israels outright attacks in the Gaza Strip rely on “precision” aerial strikes, not carpetbombing. Such attacks on the whole population would be condemned by the world. Israels most effective means of controlling Gaza have been through economic sanction and control of its borders. By working through both tunnels and bridges, this project might subvert some of the same border issues present in Gaza.

And on top of that (ha), having all housing floating in the air removes from the playing field one of Israels favorite military machines: the bulldozer.

Oh, and just for an interesting comparison: The RAND Corporations Palestinian infrastructure proposal:

http://www.rand.org/pubs/research_briefs/RB9119/index1.html

You can see a four part blog series on this project at Fourcultures.

http://fourcultures.com

you can see a similar project designed for Manchester City Center here at BRYON HALE_ARCHITECTURE

http://byronhalearchi.blogspot.com/2009/12/future-of-our-citymanchester-city-wall.html#more

This project is not a solution for the conflict. The solution is ending the Israeli occupation of Palestine, and a one state solution -eventually- which gives equal rights to all people recognizing the right of the Palestinians to their land (the current West-Bank, Gaza, and "Israel") while still giving the "Israelis" the right of residency in the land (which does not belong to them).