[Image: (Untitled) by Priscilla Monge, photographed by Alexandra Wolkowicz. Part of the 2006 Liverpool Biennial].

[Image: (Untitled) by Priscilla Monge, photographed by Alexandra Wolkowicz. Part of the 2006 Liverpool Biennial].

A post earlier this week here on BLDGBLOG raised the question of whether or not an urban candidate might be inherently better suited for the job of U.S. president than a rural one – but what exactly do we mean when we say “urban”?

When we read that the world is rapidly urbanizing, for instance, and that more than 50% of the earth’s human population now lives in cities, what do we mean by “cities” and how can we tell when a dense assortment of buildings becomes a truly “urban” experience?

What if we are surrounded by more buildings than ever before – but there isn’t a single real city in sight?

[Image: The Garston Embassy, of the Artistic Republic of Garston, part of the Liverpool Biennial International 08].

[Image: The Garston Embassy, of the Artistic Republic of Garston, part of the Liverpool Biennial International 08].

This summer I was commissioned by the recently opened Liverpool Biennial International 08 – the theme of which is MADE UP – to write an essay about the idea of “made-up” cities. That essay, called “The Game,” was just published in the Biennial’s gigantic, 300-page catalog alongside stories and essays by Haruki Murakami, Bruno Latour, Jonathan Allen, Rana Dasgupta, Brian Hatton, and many others.

“The Game” explores the idea that we might not actually know what it means to be urban, using a remark by Ole Bouman as a jumping-off point. In an essay of his own called “Desperate Decadence,” published in Volume magazine #6, Bouman writes: “We have come to take for granted that those locations with large congregations of architecture must be cities.”

I’ve re-posted the complete essay below.

• • • [Image: The Liverpool Biennial International 08].

[Image: The Liverpool Biennial International 08].

The internet briefly lit up two years ago with the story of Gilles Tréhin, an autistic savant, artist, and amateur urban planner who had invented a city that he calls Urville. Urville, imagined as an island metropolis for 12 million inhabitants, begun when Tréhin was only five years old, is a triumphant example of a city made up almost from nothing. Tréhin’s own guidebook to the city includes hundreds of perspectival pencil drawings; these depict, in often astonishing detail, recognizable buildings and building types that have been combined to form a cityscape that itself exceeds recognition.

With imaginary spaces like the Square des Mille Astres, the Gare d’Italie, and the Place des Tégartines, Urville’s visual appearance could perhaps be described as a kind of Belgian Venice, crossbred with Chicago, as master-planned by Baron Hausmann for an upstart hotelier in Las Vegas. In other words, the city is derivative; it is a collection of landmarks. One can make out the Sears Tower, the Rialto Bridge, the Grande Arche de La Défense, and what could easily pass for New York’s World Trade Center towers—among many other sites on the global tourist circuit—but what Urville lacks is a human face. Although the jacket of Tréhin’s book explains that the city comes complete with “cultural anecdotes grounded in historical reality,” including the long-lasting spatial effects of Vichy France, World War II, and what is broadly referred to as globalization, the city is something of a void, an open-air museum of unchallenging urban artifacts.

As Charlotte Moore wrote for the Guardian back in May 2006, Urville is “curiously timeless, swept clean of the detritus of human lives.” She suggests that the city even has “no sense of character.” Indeed, Urville is a strange sight. It is vast, referentially comprehensive, and visually detailed—but, outside of its sheer curiosity, there is very little there that might recommend a visit. It is Brussels or The Hague. One might even say that Urville is framed to avoid the emotional vicissitudes of everyday life.

Urville has plenty of buildings—but there is no real city.

[Image: (Untitled) by Matej Andraz Vogrincic, photographed by Alexandra Wolkowicz. Part of the 2006 Liverpool Biennial].

[Image: (Untitled) by Matej Andraz Vogrincic, photographed by Alexandra Wolkowicz. Part of the 2006 Liverpool Biennial].

In a short essay called “Desperate Decadence,” published in Volume magazine #6, Ole Bouman quips: “We have come to take for granted that those locations with large congregations of architecture must be cities.” When I later asked him about this comment during an interview, he added: “If you don’t distinguish between those two—if you think that applying urban form is the same as building a city, or even creating urban culture—then you make a very big mistake.” The question, then, in this context, is: Is it possible to invent—to make up—a city that isn’t simply a collection of buildings? Is it possible to create a genuine city from nothing—or can we only construct large congregations of architecture?

We’ve all heard by now, for instance, that for the first time in history the majority of our species—more than 50% of the Earth’s human population—lives in an urban environment today. We’ve been told, by journalists intoxicated with the superlative, that this a moment of great Darwinian consequence, an evolutionary point of no return. More urbanized than we have ever been before, have humans have apparently changed the very nature of the species: Humans are now animals that live together in cities. We are builders, dwellers and thinkers of towers and streets.

But for all the talk of the ancient hunter-gatherer finally succumbing to the bright lights of the big city, it is not at all clear that we even know what cities really are. Can we be certain, for all of the buildings currently under construction in places like Dubai, Shenzhen, and even Dallas-Ft. Worth, that it is cities we are creating? We are surrounded by more buildings than ever before, but perhaps this observation alone is not enough to say that human life has been thoroughly urbanized.

[Image: Air-Port-City by Tomas Saraceno, photographed by Adatabase. “Since 2002,” we read in the Biennial’s pocket guide, “Saraceno has continued, in sculptures, installations and experimental flights, to make a series of incremental steps towards his ultimate goal of cities built in the air.” From the Liverpool Biennial International 08].

[Image: Air-Port-City by Tomas Saraceno, photographed by Adatabase. “Since 2002,” we read in the Biennial’s pocket guide, “Saraceno has continued, in sculptures, installations and experimental flights, to make a series of incremental steps towards his ultimate goal of cities built in the air.” From the Liverpool Biennial International 08].

An interesting analogy comes to us here from the history of videogame design. In her 2001 pamphlet called Utopian Entrepreneur, published by MIT, author Brenda Laurel describes what she calls an “ugly” time in the corporate career of videogame super-firm Atari. In 1984, Atari’s sales figures, reputation, and game quality all began to nosedive. “So began the great videogame darkness of 1984 that lasted until almost the end of that decade,” she writes. But what exactly happened—and how does it relate to urban design?

“The Atari corporation paid very little attention to designing for computer games,” Laurel diagnoses. After all, “no one except a few isolated programmers who actually built the games was looking at the requirements for good interactivity, play patterns, or design principles.” Worse still, “There was no market research on what players liked in a game.” In other words, entire games and game worlds were being produced from scratch, without any real grasp of what might make a game work.

At the same time, hordes of Harvard MBAs began churning out business plans, and transplants from aerospace middle management drew up elaborate production schedules, and Procter & Gamble veterans happily began planning marketing and distribution. Great commercials were produced. Except for the programmers, however, no one was in the business of creating great videogames.

Atari had a stellar business plan and a first-rate marketing team—but, for all intents and purposes, it had nothing interesting to sell.

Following the logic of this example, it is easy enough to see Dubai—or even Tucson, Arizona—as a failed videogame in the desert, ironically under-designed and over-promoted. One could even say that we have perfected the art of the anti-city—that we have made up anything but truly urban environments. Dubai, for instance, is famously difficult to navigate on foot, requiring a ten minute car ride down six-lane motorways, complete with frequently lethal U-turns, simply to get to the hotel across the street. The city has a sum total of eleven pedestrian bridges—and twenty-five percent of the world’s cranes. While pedestrian-friendliness is by no means the only marker of ‘good interactivity, play patterns, or design principles’ in a future metropolis, it is nonetheless worth highlighting the disjunction here between the city as a dense, somewhat autistic collection of buildings and the city as a user-friendly environment.

It’s as if Dubai has perfected the art of construction, but in securing a market niche it has forgotten what needed to be built. Paraphrasing Brenda Laurel, perhaps Dubai did not do enough “market research on what players liked in a game”—only here the game is a city.

[Image: Opertus Lunula Umbra (Hidden Shadow of Moon) by U-Ram Choe, part of the artist’s “archaeology of undiscovered futuristic organisms,” photographed by Adatabase. Part of the Liverpool Biennial International 08].

[Image: Opertus Lunula Umbra (Hidden Shadow of Moon) by U-Ram Choe, part of the artist’s “archaeology of undiscovered futuristic organisms,” photographed by Adatabase. Part of the Liverpool Biennial International 08].

But cities today are well known for popping up in the middle of nowhere, history-less and incomprehensible. There are slums, refugee camps, army bases—and Dubai. That’s what cities now do. If these cities are here today, they weren’t five years ago; if they’re not here now, they will be soon. Today’s cities are made up, viral, fungal, unexpected. Like well-lit film sets in the distance, staged amidst mudflats, reflecting themselves in the still waters of inland reservoirs, today’s cities simply arrive, without reservations; they are not so much invited as they are impossible to turn away. Cities now erupt and linger; they are both too early and far too late. Cities move in, take root and expand, whole neighborhoods throwing themselves together in convulsions of glass and steel.

Except, as Mike Davis memorably points out in his recent book Planet of Slums, the “cities of the future, rather than being made out of glass and steel as envisioned by earlier generations of urbanists, are instead largely constructed out of crude brick, straw, recycled plastic, cement blocks, and scrap wood. Instead of cities of light soaring toward heaven, much of the twenty-first-century urban world squats in squalor, surrounded by pollution, excrement, and decay.” This is “pirate urbanization,” he writes, and it consists of “anarchic” anti-cities on the fringes of “cyber-modernity.” We might be making up new cities everywhere around the world today, but very few of them look like Norman Foster’s eco-metropolis of Masdar, that well-rendered city constructed from nothing but petrodollars atop the sands of Abu Dhabi. Davis writes, or example, that, in “an archipelago of 10 slums” outside Bangalore, India, “researchers found only 19 latrines for 102,000 residents.” There is thus what Davis calls an ‘excremental surplus’ to these rapidly expanding environments—yet these are the landscapes to which we refer when we say that humans have become an urban species.

These are not cities in any recognised infrastructural or legislative sense; they are, rather, dense collections of buildings. In contrast to Dubai’s Atari–like desert failure, with its arid combination of over-thought business plans and an absolute lack of content, these super-slums compress far too much content into a radically unplanned space.

[Image: The Gleaming Lights of the Souls by Yayoi Kusama, photographed by Adatabase. Part of the Liverpool Biennial International 08].

[Image: The Gleaming Lights of the Souls by Yayoi Kusama, photographed by Adatabase. Part of the Liverpool Biennial International 08].

On the other hand, sometimes a made-up city does not even require acts of construction. That is, what might appear simply to be a field of cloned single-family houses, buffered by vast tracts of manicured green space, can be transformed into a city with the stroke of a pen. Cities are thus created everyday, in other words, within the administrative guidelines for managing inhabited landscapes—and no new ground need ever be broken. These made-up cities are, in fact, boomburbs, according to Robert Lang and Jennifer LeFurgy, two sociologists with the Washington D.C.-based Brookings Institution.

In their 2007 book, Boomburbs: The Rise of America’s Accidental Cities, Lang and LeFurgy explain that many of the largest cities in the United States today are simply hypertrophied suburbs—they are boomburbs. The mayors of established cities have had a hard time adjusting to this fact. Mesa, Arizona, for instance, an otherwise anonymous tumescence on the air-conditioned desert edge of Phoenix, is a “stealth city”: Its population, incredibly, is larger than both Minneapolis–St. Paul and Miami. The authors also describe how the mayor of Salt Lake City once “dismissed the idea” that his city might have anything in common with suburban North Las Vegas, “despite the fact that North Las Vegas is both bigger and more ethnically diverse than Salt Lake City.” What these boomburbs have, in lieu of historic centrality and international name-recognition, is a flexible legal and financial infrastructure. They have water rights boards and waste disposal networks, even local schools and sales tax—and though they don’t necessarily have mayors (though some do), they have “landscape management” committees and homeowners associations. These are cities made up less by buildings than by tax codes and the law.

The mayor of Salt Lake City’s widely shared cognitive dissonance, being somehow unable to see that Mesa, Arizona, is bigger than a city like St. Louis—with its Eero Saarinen-designed Gateway Arch along the banks of the Mississippi—is part of what the authors call “a national ambivalence about what we have built in the past half century.” This featureless landscape of low-rise retail parks and residential cul-de-sacs—of video shops, hockey moms, and 24-hour supermarkets—has become the dominant architecture of American urbanism, despite (or perhaps because of) the fact that it remains critically invisible. One could even say that this landscape is all life and no landmarks—an almost exact inversion of Gilles Tréhin’s Urville, with its tapestry of landmarks and no signs of life. From boomburbs to Urville, via super-slums and Dubai, these instant cities take shape in less than a single generation and cross a fantastic landscape of competing urban forms.

[Image: An installation by Sarah Sze, photographed by Adatabase. Sze’s installations “are like highly organic ecosystems, colonizing the space they inhabit.” Part of the Liverpool Biennial International 08].

[Image: An installation by Sarah Sze, photographed by Adatabase. Sze’s installations “are like highly organic ecosystems, colonizing the space they inhabit.” Part of the Liverpool Biennial International 08].

Is it really possible, though, that we could continue to make up and construct the wrong kinds of cities? One could perhaps be excused here for concluding that successful cities cannot be made up at all, that there is something fundamentally unthinkable or excessive to this process, something that simply cannot be planned in advance.

But that doesn’t stop us from looking for what we believe is the secret recipe—for exactly the right balance of marketing plans, water laws, historic monuments, public spaces, and so on. A thriving subsidiary industry has thus arisen in these cities’ shadows, forming a new, deliberately carnivalesque genre of international reportage. We are city-hunting. Writers fly halfway round the world to describe their newest adventures in Middle Eastern air-conditioning. These are new sights in human history, we’re told, and they’re meant to dazzle the modern mind. Every urban day is remarkable, we read, for it is different—and somehow bigger, more extreme—than the last.

So if we continue to get so many things about our cities so wrong, then the only thing to do is to keep looking—to track down Zaha Hadid’s newest building, to host design competitions for skyscrapers in St. Petersburg, to commission private islands, domes, and pyramids. We experiment with Olympic Villages. Amidst all of the dust and the eye-popping budgets, it seems impossible to believe that we won’t get at least one place right.

It’s as if, hovering there in the future possible tense, at the imaginative vanishing point of urban design itself, is the perfect city, sending ripple effects back into the spaces of today—and we can trace the outlines of its utopian arrival in the empty streets and construction sites of the spaces that now surround us.

Because it no longer matters if we are wrong about our cities; we will always be right if we just make up more.

[Image: Dubai’s “carbon-neutral” ziggurat, designed by Timelinks].

[Image: Dubai’s “carbon-neutral” ziggurat, designed by Timelinks]. [Image: Park Gate, Dubai, by Adrian Smith + Gordon Gill Architecture].

[Image: Park Gate, Dubai, by Adrian Smith + Gordon Gill Architecture]. [Image: New Songdo City, South Korea].

[Image: New Songdo City, South Korea].

[Image: RAK Gateway, Ras Al Khaimah, United Arab Emirates, by OMA].

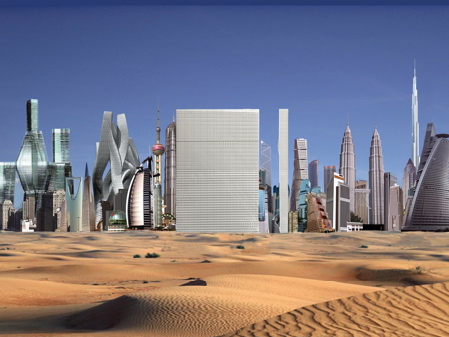

[Image: RAK Gateway, Ras Al Khaimah, United Arab Emirates, by OMA]. [Image: Contemporary architecture’s well-rendered visual overload, parodically assembled by OMA].

[Image: Contemporary architecture’s well-rendered visual overload, parodically assembled by OMA].

[Images: Waterfront City masterplan, Dubai, by OMA. It’s worth reading counter-discussions of this project by Nicolai Ouroussoff and Lebbeus Woods, respectively].

[Images: Waterfront City masterplan, Dubai, by OMA. It’s worth reading counter-discussions of this project by Nicolai Ouroussoff and Lebbeus Woods, respectively]. [Image: By

[Image: By

[Images: All works by

[Images: All works by  [Image: From the “atlas of hidden water.” Check out the

[Image: From the “atlas of hidden water.” Check out the  [Image: The “hidden water” of South America].

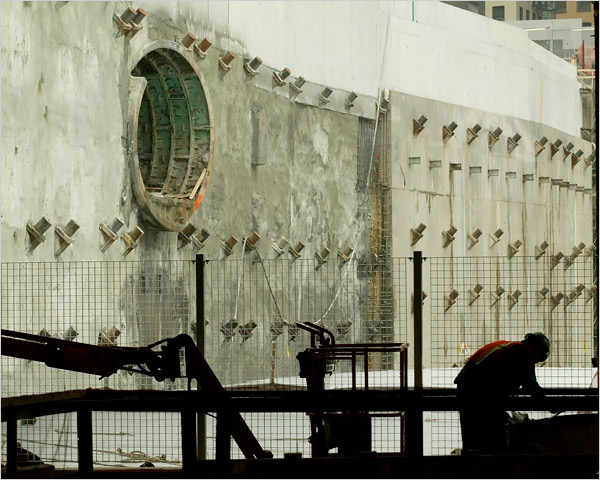

[Image: The “hidden water” of South America]. [Image: Photo by Andrea Mohin for

[Image: Photo by Andrea Mohin for  [Image: Photo by Fred R. Conrad for

[Image: Photo by Fred R. Conrad for  [Image: Photo by David W. Dunlap for

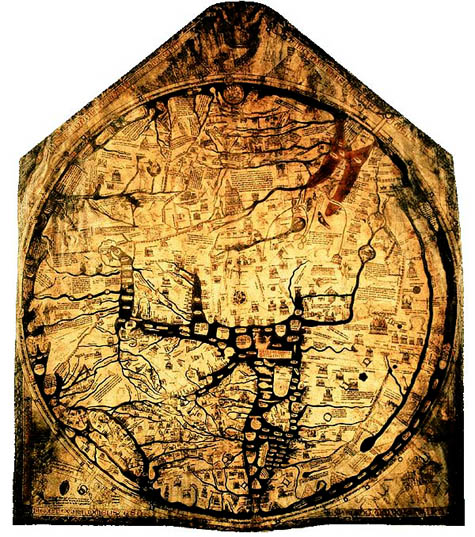

[Image: Photo by David W. Dunlap for  [Image: The charismatic boundaries of an earlier worldview – here, the Hereford

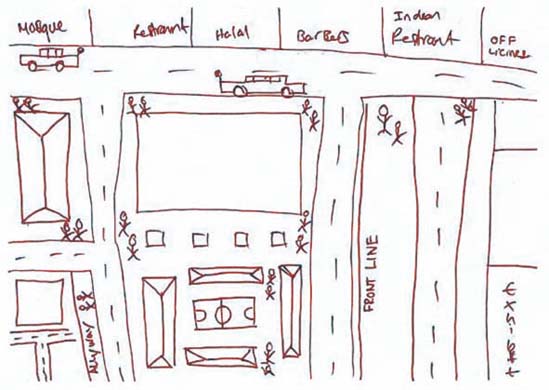

[Image: The charismatic boundaries of an earlier worldview – here, the Hereford  [Image: From the

[Image: From the

[Images: From the

[Images: From the  [Image: London waste towers, designed by

[Image: London waste towers, designed by  [Image: London waste towers, designed by

[Image: London waste towers, designed by  [Image: London waste towers, designed by

[Image: London waste towers, designed by  [Image: London waste towers, designed by

[Image: London waste towers, designed by  [Image: The Large Hadron Collider photographed by Claudia Marcelloni, ©CERN, via

[Image: The Large Hadron Collider photographed by Claudia Marcelloni, ©CERN, via  [Image: Photo by Ryan Collerd for

[Image: Photo by Ryan Collerd for  [Image: Riding zip lines to Oakland; by

[Image: Riding zip lines to Oakland; by  [Image:

[Image:  [Image: The

[Image: The  [Image: The

[Image: The  [Image:

[Image:  [Image:

[Image:  [Image:

[Image:  [Image:

[Image:  [Image: An installation by

[Image: An installation by  [Image: Duncraig Castle, Scotland; photo by Margaret Salmon and Dean Wiand for

[Image: Duncraig Castle, Scotland; photo by Margaret Salmon and Dean Wiand for  [Image: Duncraig Castle, Scotland; photo by Margaret Salmon and Dean Wiand for

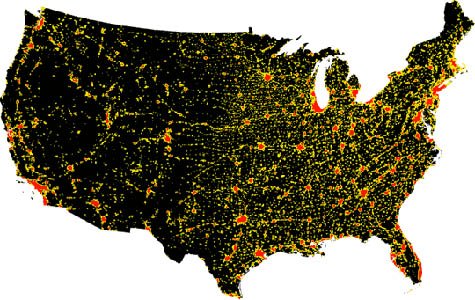

[Image: Duncraig Castle, Scotland; photo by Margaret Salmon and Dean Wiand for  [Image: The population density of the United States, ca. 2000, via

[Image: The population density of the United States, ca. 2000, via  [Image: A street in

[Image: A street in  [Image: Urban areas in the U.S. Map courtesy of

[Image: Urban areas in the U.S. Map courtesy of  [Images: From the

[Images: From the