[Image: Bannerman’s Island, copyright Shaun O’Boyle].

[Image: Bannerman’s Island, copyright Shaun O’Boyle].

I have a thing for abandoned islands, so I was excited to see Shaun O’Boyle‘s photo series of Bannerman’s Island, an old, half-flooded and fire-damaged derelict mansion built on a small island in the Hudson River.

[Images: Bannerman’s Island, copyright Shaun O’Boyle].

[Images: Bannerman’s Island, copyright Shaun O’Boyle].

As American Heritage describes it, “this island fortress was once the private arsenal of the world’s largest arms dealer.” And that was Frank “Francis” Bannerman.

Bannerman, we learn, “bought up ninety per cent of all captured guns, ammunition, and other equipment auctioned off after the Spanish-American War. He also bought weapons directly from the Spanish government before it evacuated Cuba. These purchases vastly exceeded the firm’s capacity at its store in Manhattan and filled three huge Brooklyn warehouses with munitions, including thirty million cartridges.” Accordinglty, “Bannerman now needed an arsenal.”

Or, more accurately speaking: he needed a private island.

[Image: Bannerman’s Island, copyright Shaun O’Boyle].

[Image: Bannerman’s Island, copyright Shaun O’Boyle].

Bannerman soon purchased “six and a half acres of scrub-covered rock called Polopel’s Island, about fifty-five miles north of New York City.” But even that wasn’t enough. He then “bought seven acres more of underwater land in front of the island from the state of New York. He ringed the submerged area with sunken canalboats, barges, and railroad floats to form a breakwater” – a kind of artificial reef.

“The island was under continuous construction for eighteen years.”

[Image: Bannerman’s Island, copyright Shaun O’Boyle].

[Image: Bannerman’s Island, copyright Shaun O’Boyle].

Quoting at length:

The castle was Bannerman’s vision and his execution. It was creviced and encrusted with battlements, towers, turrets, crenellations, parapets, embrasures, casements, and corbelling. Huge iron baskets suspended from the castle corners held gas-fed lamps that burned in the night like ancient torches. By day Bannerman’s castle gave the river a fairyland aspect. By night it threw a brooding silhouette against the Hudson skyline.

[Image: Bannerman’s Island, copyright Shaun O’Boyle].

[Image: Bannerman’s Island, copyright Shaun O’Boyle].

More:

Visitors approached the place along a breakwater bristling with cannon and then passed through an opening flanked by two watchtowers. After tying up their boat at a large unloading dock they crossed a moat spanned by a drawbridge and passed under a portcullis crowned by the Bannerman coat of arms carved in stone.

Bannerman died a week after the end of World War I – and the island had sunk into a state of “monumental decay” by the 1960s.

It was then gutted by arsonists.

And then photographer Shaun O’Boyle came into the picture.

[Image: Bannerman’s Island, copyright Shaun O’Boyle].

[Image: Bannerman’s Island, copyright Shaun O’Boyle].

“I found the island,” Shaun explained to me over email, “while commuting to NYC via the Amtrak train along the east bank of the Hudson River, which passes by the island and is plainly visible. It is located north of Cold Spring, NY, and can be seen when crossing the Beacon Bridge.”

“New York state owns the island now,” O’Boyle added, “and there are renovations going on, but I’m not sure what their plans are for public access. You can take tours of the island, via kayak, or motor boat.”

[Image: Bannerman’s Island, copyright Shaun O’Boyle].

[Image: Bannerman’s Island, copyright Shaun O’Boyle].

O’Boyle goes on to describe how he “explored the island using a kayak with friends,” and that he’s “made 3 visits, 2 in the past 2 years. The last visit we climbed the mountain adjacent to the river,” he adds, “and that is where the aerial views are from.”

When I asked him about what appear to be flooded foundation walls, ringing the island like a tropical atoll, Shaun said: “What look like sunken foundations in the Hudson are actually part of the breakwater constructed to form a harbor for unloading the ships of supplies.”

And when I asked him about the actual construction of the building – how the ruined walls handle themselves today, maintaining their shape and structure – O’Boyle wrote that “the construction quality was lacking, and I heard that Bannerman used old musket barrels to reinforce some of the concrete walls.”

Architecture as a kind of thinly described weapon: like almost all archaeology, scrape deep enough and you’ll uncover the residues of warfare.

[Images: Bannerman’s Island, copyright Shaun O’Boyle].

[Images: Bannerman’s Island, copyright Shaun O’Boyle].

O’Boyle:

The island is a beautiful place. I have been there in the mid-summer only, and thick vegetation covers everything, making it a challenge to move around anywhere but the paths. It certainly is a different kind of ruin for me to photograph: most of my photography work is of large scale industrial ruins, like Bethlehem Steel, and some of the industries that feed the steel mills – like coal and mining. Although my latest work is a bit different, I have been photographing the coal mining region of Pennsylvania – the towns, buildings and landscapes. It’s a fascinating area. But Bannerman’s is a more romantic ruin, set among the beautiful hills of the Hudson river.

It’s also the perfect setting for a future Patrick McGrath novel.

And the island – or at least Bannerman’s arsenal – has had its effects elsewhere. As O’Boyle explained, Bannerman “published a catalogue of all his products – Bannermans Catalogue – and, in fact, I currently have a 1925 edition on order from a used book store. Word has it that many of the canons you find in front of American Legions and town halls around the country are from Bannermans.”

[Images: Bannerman’s Island, copyright Shaun O’Boyle].

[Images: Bannerman’s Island, copyright Shaun O’Boyle].

Don’t miss the rest of O’Boyle’s website, Modern Ruins, including his exquisite visual tour of Philadelphia’s Eastern State Penitentiary – where my wife once worked as a tour guide – as well as this freaky crypt.

Of course, you can also support the artist by purchasing a print.

Finally, you can read more about Bannerman’s Island here and here – and, while you’re at it, why not read a bit about Boldt Castle, another ruined, island-bound mansion, this one standing amidst vegetation further north in the Thousand Islands. I used to visit that place as a kid; we’d go up to see my grandpa, a boatbuilder, who lived on one of the nearby islands, and then we’d toot on over to Boldt Castle.

[Image: Mari Tefre for Getty Images, via the

[Image: Mari Tefre for Getty Images, via the  MediaSCAPES, for those curious, describes itself as follows:

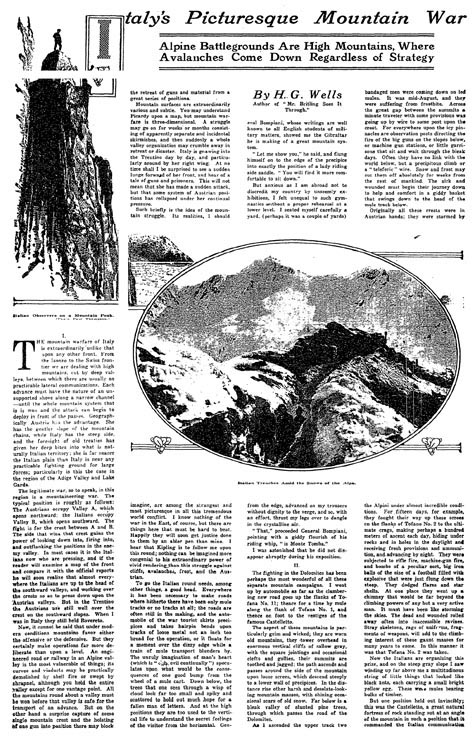

MediaSCAPES, for those curious, describes itself as follows: Being inclined to spend time remembering things, I just made

Being inclined to spend time remembering things, I just made  [Image: Cover illustration by

[Image: Cover illustration by  [Image: An unrelated vision of London’s sci-fi future from Maurice Elvey’s 1928 film, High Treason, mentioned in

[Image: An unrelated vision of London’s sci-fi future from Maurice Elvey’s 1928 film, High Treason, mentioned in

[Images: The

[Images: The  [Image: An aerial view of the bombing of Dresden during World War II; photo via

[Image: An aerial view of the bombing of Dresden during World War II; photo via

[Image: At the self-interconnected heights of

[Image: At the self-interconnected heights of  [Image: The fortified peaks of the

[Image: The fortified peaks of the  [Image: Found via, copyrighted to, and courtesy of

[Image: Found via, copyrighted to, and courtesy of  [Image: A machine gun nest embedded in the Italian mountainside; found via, copyrighted to, and courtesy of

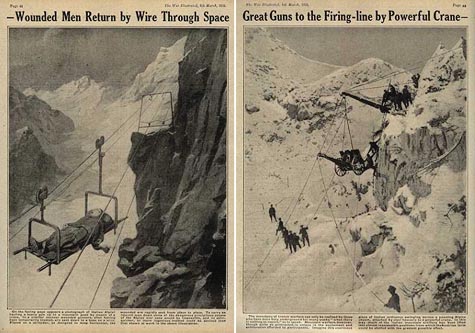

[Image: A machine gun nest embedded in the Italian mountainside; found via, copyrighted to, and courtesy of  [Images: Wounded men returning by wire through space as cannons are raised into place by cranes;

[Images: Wounded men returning by wire through space as cannons are raised into place by cranes;  [Image: Found via, copyrighted to, and courtesy of

[Image: Found via, copyrighted to, and courtesy of  [Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: Courtesy of

[Image: Courtesy of  Of course, all of this made me think of “

Of course, all of this made me think of “ The man explains to our friendly narrator – who, for reasons of his own, has decided to visit this guy, overlooking his “repellent unkemptness” and “wild disorder of dress” – that:

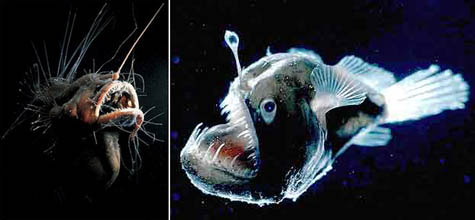

The man explains to our friendly narrator – who, for reasons of his own, has decided to visit this guy, overlooking his “repellent unkemptness” and “wild disorder of dress” – that: Soon, the narrator shouts, there are “huge animate things brushing past me.” These are “disgusting” and “indescribable shapes” like “jellyfish monstrosities” that “flabbily quive[r] in harmony with the vibrations from the machine.”

Soon, the narrator shouts, there are “huge animate things brushing past me.” These are “disgusting” and “indescribable shapes” like “jellyfish monstrosities” that “flabbily quive[r] in harmony with the vibrations from the machine.”  So what happens when scientists fully assemble this vast and sprawling neutrino detector at the bottom of the Mediterranean Sea, within sight of ruined arches onshore and Piranesian streetscapes, only to find themselves detecting, in a chaos of vibration and flashing light, previously unknown and hostile forms of maritime life?

So what happens when scientists fully assemble this vast and sprawling neutrino detector at the bottom of the Mediterranean Sea, within sight of ruined arches onshore and Piranesian streetscapes, only to find themselves detecting, in a chaos of vibration and flashing light, previously unknown and hostile forms of maritime life?  [Image: The “

[Image: The “

[Image: Two stitched panoramas of the Adirondacks: (top)

[Image: Two stitched panoramas of the Adirondacks: (top)  [Image: “

[Image: “