The New York Times reports today on what it calls the “Pompeii of World War II,” an abandoned village in Italy now “overtaken by vines and lime trees.”

That village is San Pietro, an “11th-century cobblestone mountain village nestled among wild figs and cactus,” as well as the scene of months of horrific fighting between Allied and German troops.

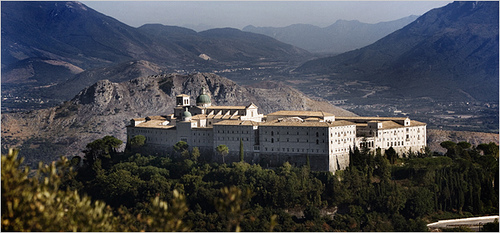

[Image: The reconstructed abbey atop Monte Cassino, as photographed by Stephanie Kuykendal for The New York Times].

[Image: The reconstructed abbey atop Monte Cassino, as photographed by Stephanie Kuykendal for The New York Times].

Nearby, atop Monte Cassino, was “one of the holiest sites in Christendom,” a monastery “founded by St. Benedict in the sixth century, a shrine of Western civilization” – indeed, “a center of art and culture dating back nearly to the Roman Empire” – which the Allies bombed into rubble, suspecting (or not suspecting, but caught up nonetheless in the machinations of bad intelligence and unquestioned orders) that German troops had taken refuge there.

“After the battle ended,” we read, the entire chain of small mountain valleys in which San Pietro once stood “would be left uninhabitable for years, demolished by Allied bombs, beset by malaria.”

So this may be a bit rambling, and otherwise unrelated, but while working on The BLDGBLOG Book tonight (due out Spring 2009! from Chronicle Books! buy loads!), I was re-reading W.G. Sebald’s extraordinary On the Natural History of Destruction.

At one point in the book Sebald describes the literally shell-locked life of people who had managed to stay on in the destroyed cities of northern Germany during WWII. He describes “the unappetizing meals they concocted from dirty, wrinkled vegetables and dubious scraps of meat, the cold and hunger that reigned in those underground caverns, the evil fumes, the water that always stood on the cellar floors, the coughing children and their battered and sodden shoes.”

Battling grotesquely bloated rats and enormous green flies, these “cave dwellers,” as Sebald calls them, lived with the “multiplication of species that are usually suppressed in every possible way,” amidst the gravel and shattered windowframes of their now “ravaged city.”

Based on an eyewitness account written by an Allied Air Commander, Sebald then refers to “the terrible and deeply disturbing sight of the apparently aimless wanderings of millions of homeless people amidst the monstrous destruction, [which] makes it clear how close to extinction many of them really were in the ruined cities at the end of the war.”

For some reason the next line just haunts me:

No one knew where the homeless stayed, although lights among the ruins after dark showed where they had moved in.

Which leads me to ask myself whether it’s simply a factor of my age – I’m not exactly getting younger here – though I do drink a lot of orange juice – or if it’s something more closely related to the weirdly militarized political climate in which we now live, but I’ve started to react to things like this with a kind of concentrated studiousness, as if reading – absurdly – for advice on how to survive my own generation’s coming, perhaps even more calamitous, future.

What “monstrous destruction” of world war and oil shortages and global terror and climate change might we, too, have to face someday?

In twenty years’ time will I be out holding up some pathetic light among the ruins of a destroyed city, wondering where my wife is, dying of thirst, deaf in one ear, covered in radiation burns?

Or is that just a peculiarly American form of pessimist survivalism? Or do I just read too much Sebald?

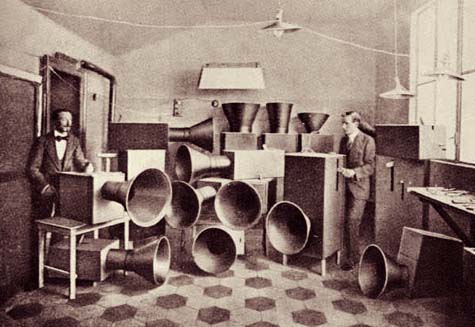

[Image:

[Image:  Some of the “surprisingly agreeable” sounds discovered thus far include “car tyres on wet, bumpy asphalt, the distant roar of a motorway flyover, the rumble of an overground train and the thud of heavy bass heard on the street outside a nightclub.”

Some of the “surprisingly agreeable” sounds discovered thus far include “car tyres on wet, bumpy asphalt, the distant roar of a motorway flyover, the rumble of an overground train and the thud of heavy bass heard on the street outside a nightclub.” [Image: The South Tower of the World Trade Center on 9/11; photographer unknown].

[Image: The South Tower of the World Trade Center on 9/11; photographer unknown]. [Image: “Within a few hours’ time, a person exposed to the fumes could ingest toxins that would otherwise take a year to accumulate in a typical environment”; photographer unknown].

[Image: “Within a few hours’ time, a person exposed to the fumes could ingest toxins that would otherwise take a year to accumulate in a typical environment”; photographer unknown]. [Image: After the towers’ collapse; photographer unknown].

[Image: After the towers’ collapse; photographer unknown]. [Image: Famous buildings in Chicago, via the

[Image: Famous buildings in Chicago, via the  [Image: Glowing pavilion by

[Image: Glowing pavilion by  [Image: A spectacular glimpse of the Leonid meteor shower, circa 1999; photo by

[Image: A spectacular glimpse of the Leonid meteor shower, circa 1999; photo by  [Image: Habitat 825, by

[Image: Habitat 825, by

[Images: Habitat 825, by

[Images: Habitat 825, by  Case in point: the St. Marylebone school.

Case in point: the St. Marylebone school.

[Images: Gardner 1050, by

[Images: Gardner 1050, by

[Images: The Fineman house, by

[Images: The Fineman house, by  [Image: Proposal for CalArts, by

[Image: Proposal for CalArts, by  [Image: The Norton Avenue Lofts, by

[Image: The Norton Avenue Lofts, by

[Images: The Norton Avenue Lofts, by

[Images: The Norton Avenue Lofts, by  [Image: 12 Houses by architect

[Image: 12 Houses by architect  [Image: 12 Houses by architect

[Image: 12 Houses by architect  [Image: 12 Houses by architect

[Image: 12 Houses by architect  North Carolina-based architect

North Carolina-based architect  [Images: The

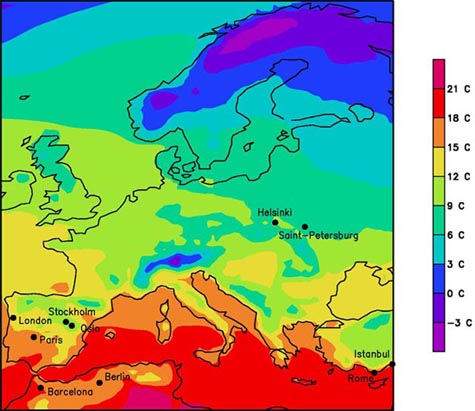

[Images: The  The map is initially quite confusing, but it shows that London will have the climate of Lisbon, Portugal; Berlin will have the climate of northern Algeria (!); and Oslo will feel like Barcelona (and so on).

The map is initially quite confusing, but it shows that London will have the climate of Lisbon, Portugal; Berlin will have the climate of northern Algeria (!); and Oslo will feel like Barcelona (and so on).