[Image: ©Renae Baker].

[Image: ©Renae Baker].

“Some of the coldest temperatures on Earth brought a rare cloud formation to the skies over Antarctica,” SF Gate reports. “Meteorological officer Renae Baker captured spectacular images of the nacreous clouds, also known as polar stratospheric clouds, last week at Australia’s Mawson station.”

[Image: ©Renae Baker].

[Image: ©Renae Baker].

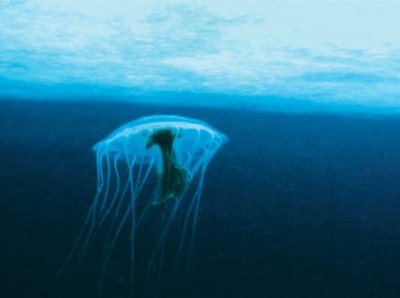

Meanwhile, Wired introduced us last month to Werner Herzog’s forthcoming science fiction film, The Wild Blue Yonder, which uses the undersea Antarctic seascape as a stand-in for liquid extraterrestrial environments.

[Image: Werner Herzog/Wired – many more photos here].

[Image: Werner Herzog/Wired – many more photos here].

“Instead of spending millions on Spielberg-style effects, Herzog went low tech and high geek,” Wired writes. “He spliced together documentary footage from NASA and the National Science Foundation’s US Antarctic Program. He created ‘characters’ from documentary-style scenes with actual physicists and astronauts.”

[Image: Werner Herzog/Wired].

[Image: Werner Herzog/Wired].

Apparently, whilst viewing “mesmerizing images of ethereal jellyfish and swarms of crystalline microorganisms mingling in a cobalt twilight beneath a 20-foot-thick sheet of ice,” Herzog instinctively felt: “This is not our planet.” (One assumes the sentiment should, in Herzog’s case, be taken literally).

[Image: Werner Herzog/Wired].

[Image: Werner Herzog/Wired].

The film “opens with a wide shot,” Wired explains: “A vast, vaulted ice canopy stretches over the horizon as two human silhouettes descend through a glowing portal into the dim indigo void. They fan out weightlessly, their breath echoing like whispers in an empty cathedral. Something approaches – a speck, silently swelling into what looks like a translucent bullet lined with undulating fringes of silk. The creature hovers in close-up, then darts away in a cascade of ice shards; dissonant music fades, then swells as the humans forge farther into the blue-green deep.”

[Image: NOAA – who, elsewhere, presents us with the literature of abysses].

[Image: NOAA – who, elsewhere, presents us with the literature of abysses].

That “blue-green deep,” however, is also an uncanny incubator of evolutionary weirdness. The deep sea octopus, for instance, first made its appearance in Antarctica’s waters: “Australian researcher Dr. Jan Strugnell of Queen’s University Belfast and the British Antarctic Survey says the formation of ocean currents around the continent millions of years ago provided the right conditions for ocean creatures to evolve,” the Australian Broadcasting Corporation reports.

Amazingly, deep sea octopi appear to register, in their genes and anatomy both, the continental make-up of plate tectonics at the time of their earliest evolution – think of it as forensic landscape history at a biological remove: “About 34 million years ago, Antarctica separated completely from South America, with the opening up of Drakes Passage. This allowed the Antarctic Circumpolar Current to form, which insulated the continent and allowed it to get really cold. As cold water is more oxygen rich than warm water, oxygen from Antarctic waters would have been able to then diffuse into the deep seas along with Antarctic octopuses, which then evolved into deep sea octopuses. ‘The opening of the Drakes Passage fits in with evolution of the group,’ says Strugnell.”

Which leads me to wonder if a specific mountain range in Africa – or Asia, for that matter – catalyzed an exact and specific thousand-year microclimate in which simian ingenuity could last across sufficient generations that some group eventually opposably-thumbed its way toward a larger brain. Or a certain valley, a specific rain corridor, a particularly comfortable belt of well-grassed savannahs – these landscapes could afford the time and space in which specific organisms would gradually develop themselves and evolve.

Writing this, of course, I realize how obvious it is that that’s exactly what did happen; but, then, assuming someday we discover the exact mountain (or gorge) that helped produce a rain-shadow that helped produce a climate that helped produce a fertile niche in which tool-using hominins could hang-out long enough to discover gods, writing, and warfare, shouldn’t that specific landmark receive some kind of protected, even vaguely familial, status? The Ur-mountain.

What if it’s been turned into a copper mine?

Or if there is no such thing?

Reversing the question, of course, could you bulldoze, plow, till, and plant your way toward some wild mega-landscape specifically engineered – topographically, climatically, acidically, and so on – based upon how it will catalyze the evolution of new species in a hundred thousand years’ time? Landscape architecture as a distant subset of genetic engineering: planting your garden based on what cross-hybridized evolutionary outgrowths may someday appear – but doing this on a continental scale, and with a time-frame of eons. Landscape futures, indeed.

Werner Herzog can film the design process.

A species will look back at its originary landscape, like an octopus drifting through Antarctic waters, overwhelmed with strange feelings of gratitude.

(Big thanks to Bryan Finoki for the Antarctic clouds article!)

There’s another beautiful image of Antarctic nacreous clouds at Atmospheric Optics.

Perhaps the high atmospheres of other planets—or even our own—may host unforeseen organisms, as camouflaged in their environment as an octopus in the sea.

Consider Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s 1913 story, The Horror of the Heights:

“Conceive a jelly-fish such as sails in our summer seas, bell-shaped and of enormous size – far larger, I should judge, than the dome of St. Paul’s. It was of a light pink colour veined with a delicate green, but the whole huge fabric so tenuous that it was but a fairy outline against the dark blue sky. It pulsated with a delicate and regular rhythm. From it there depended two long drooping, green tentacles, which swayed slowly backwards and forwards. This gorgeous vision passed gently with noiseless dignity over my head, as light and fragile as a soap-bubble, and drifted upon its stately way.

I had half-turned my monoplane, that I might look after this beautiful creature, when, in a moment, I found myself amidst a perfect fleet of them, of all sizes, but none so large as the first. Some were quite small, but the majority about as big as an average balloon, and with much the same curvature at the top. There was in them a delicacy of texture and colouring which reminded me of the finest Venitian glass. Pale shades of pink and green were the prevailing tints, but all had a lovely iridescence where the sun shimmered through their dainty forms. Some hundreds of them drifted past me, a wonderful fairy squadron of strange unknown argosies of the sky – creatures whose forms and substance were so attuned to these pure heights that one could not conceive anything so delicate within actual sight or sound of earth.”

Read on: not all of them be so benign.

Beautiful photo! Thanks – and nice story, too. Nearly 20 years ago now, when I was just a kid, I read an article – though it could have been a book – full of speculative drawings of organisms that might be found in the planetary gas giants of our solar system. If something does live there, in other words, what would it look like? And I remember that Saturn – though maybe Jupiter – was imagined as the home of these weird, drifting octopus things, like methane-breathing pure nervous systems floating through unimaginably huge stormfronts hundreds of millions of miles from the sun. Though jellyfish are probably a more accurate analogy.

In any case…

Geoff,

I’ve recently seen the Wild Blue Yonder, again, at the Melbourne Film Festival. Herzog’s films are consistently intelligent and poetic and while the vocabulary of praise fails me, I can’t recommend his work highly enough. What I really like about Herzog’s way of making film is that he actually looks at the world and sees meaningful things and comments on these for the spectator, often lyrically so. For me this creates a sense of lack of constructedness, which clearly contrasts with the world-generating efforts of bigger productions. Currently I can’t express it clearer than this.

I suggest you seek his films out, esp. Aguirre, Wings of Hope (Julianes Sturz in den Dschungel), Wheel of Time even though architecture is not a main feature in the films.

cheers

Werner Herzog’s Fitzcarraldo and Les Blank’s documentary about the production, Burden Of Dreams, are both great stories about man’s artistic nature trying to make a place for itself in the midst of Nature’s obstacles.

Not that much different from architecture, actually.

Conc. nacreous clouds:

A similar weather phenomenon is quite common in Norway in winter in certain weather conditions (clouds of fine ice cristalls on crisp winter days), they are called “perlemorsky” (“mother of pearl – clouds”, plural perlemorskyer), e.g. http://astralscooter.com/MyGallery/photo.plx?img=Atmosphere/Perlemorskyer_0019.jpg

WOW! Another incredible article bout this great phenomenon. Thanx! I found another great story at Wayfaring