When large container ships can contain or ship no more, they’re sent halfway round the world to so-called “breaking yards,” where they’re dismantled (basically by hand), their metal is salvaged, and their intact structures, down to the doors and toilet seats, are put back onto the global marketplace.

Today, these yards tend to be in Bangladesh or India – but location is just a question of cheap labor and (nonexistent) environmental regulations.

It’s toxic work.

In his book The Outlaw Sea, William Langewiesche visits the Alang shipbreaking yard in Gujarat, India. It is “a shoreline strewn with industrial debris on the oily Gulf of Cambray, part of the Arabian Sea.”

His descriptions are great: “Dawn spread across the gargantuan landscape. Alang, in daylight, was barely recognizable as a beach. It was a narrow, smoke-choked industrial zone six miles long, where nearly two hundred ships stood side by side in progressive states of dissection, yawning open to expose their cavernous holds, spilling their black innards onto the tidal flats… Night watchmen were swinging the yard gates open now, revealing the individual plots, each demarcated by little flags or other markers stuck in the sand, and heavily cluttered with cut metal and nautical debris.”

He visits a hull rerolling mill where “perhaps a hundred emaciated men moved through soot and heavy smoke, feeding scrap to a roaring furnace leaking flames from cracks in the side. The noise was deafening. The heat was so intense that in places I thought it might sear my lungs. The workers’ clothes were black with carbon, as were their hair and their skin. Their faces were so sooty that their eyes seemed illuminated.”

These photographs of a shipbreaking yard in Bangladesh are all by Edward Burtynsky, however, which makes this at least my fourth post about the man – but what can I say? His work is amazing.

There’s something almost mythological in the sight of men standing round campfires amidst the toxic debris of a structure they themselves have taken apart. A displaced landscape of rare metals leaching into the sand beneath them, poisonous deltas flowing to the sea. Metallurgical micro-hydrology.

Surviving – or not – on the scraps of a first world that sent its waste elsewhere.

But what I was actually thinking – what this post was supposed to be about, in fact – was how cool it’d be if old buildings weren’t destroyed by wrecking balls, bulldozers, or well-placed explosives – they were instead uprooted in their entirety, packed onto Panamax cargo ships and dropped onto some beach somewhere, in a tropical archipelago. Complete, intact, ready for salvage. Two hundred old stone cathedrals lined up in the mist at dawn, arches ready for cutting, naves yawning open like hulls of old tankers. Behind them, American football stadiums.

On another island, skyscrapers.

Notre-Dame is collapsing? Well, ship it to the islands, where flying buttresses, arches, and colonnades are stacked round like an inland reef.

Chartres has irrepairable structural damage? The cathedral in Köln? St. Peter’s? The entire arabesque’d core of Venice? Off to the islands! Strapped to the flatbeds and cargo holds of unregistered ships, the Houses of Parliament go floating by.

The Seagrams Building? Swiss Re? Canary Wharf? The Empire State Building? The White House?

Stonehenge?

Recognizable chunks of famous architecture litter the island shores of a barely visited archipelago. Sent there on a rusting fleet of container ships.

European cathedrals overgrown with palm trees, half-buried in sand, their crypts exposed, stained glass catching every sunset. Wind-blown bank towers lilt to one side, covered in creeper vines and home to bats.

The intact floors of formerly grand 5th Avenue high-rises, complete with chandeliers, are laid-out in familiar rooms and corridors – but now they’re infested with crocodiles and half-burnt by fire.

A photojournalist arrives, walking stunned through the python-infested arches of what was once Westminster Abbey…

(With thanks to Leah Beeferman for the tip, and with the oddly synchronicitous realization that gravestmor just linked to Burtynsky’s shipbreaking photos, too…)

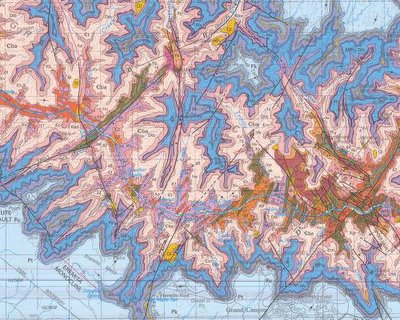

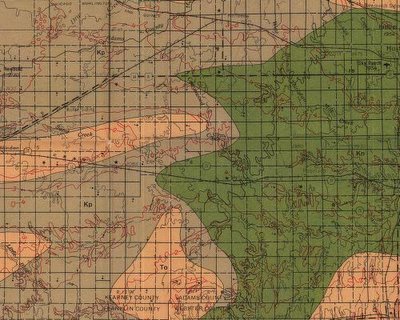

[Image: “Preferred Continental Drift”].

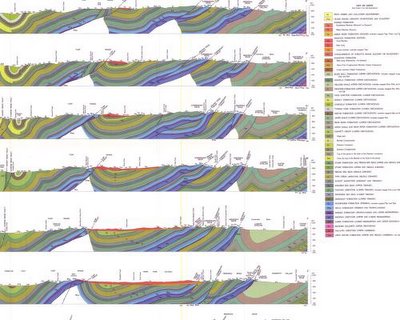

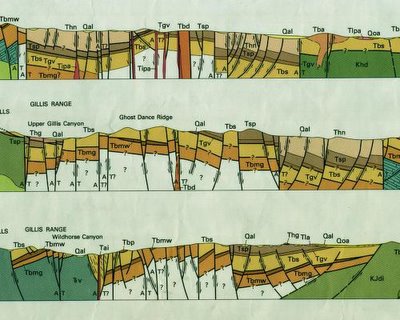

[Image: “Preferred Continental Drift”]. [Image: Global life expectancy].

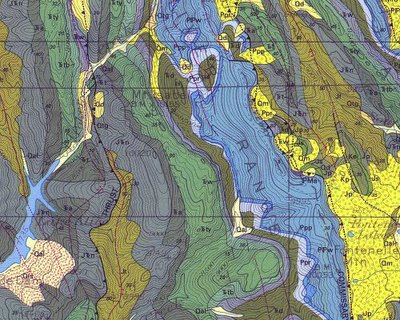

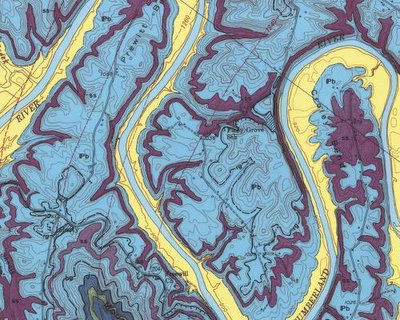

[Image: Global life expectancy]. [Image: Satellite blind spots].

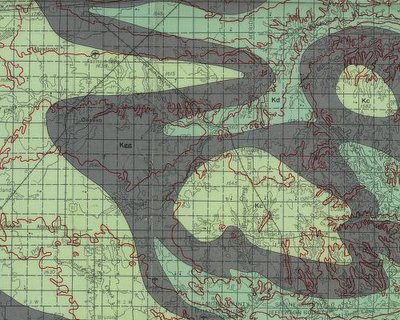

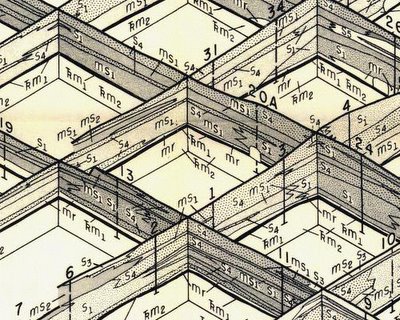

[Image: Satellite blind spots]. [Image: Nuclear energy dependency].

[Image: Nuclear energy dependency].

[Image:

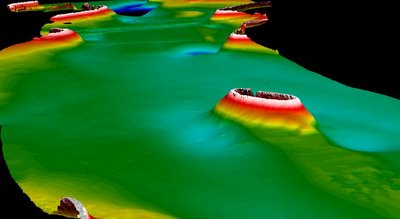

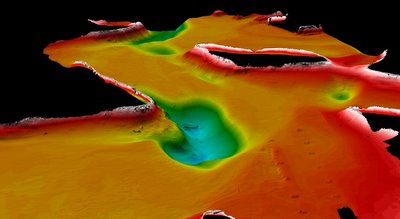

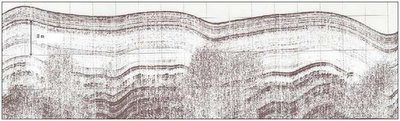

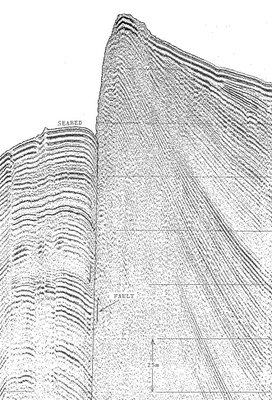

[Image:  [Image: “Ash and pumice was thrown out at vent sites along the 60km segment.”

[Image: “Ash and pumice was thrown out at vent sites along the 60km segment.”