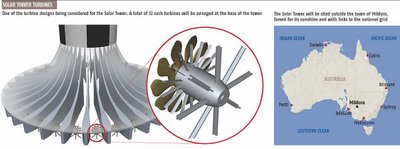

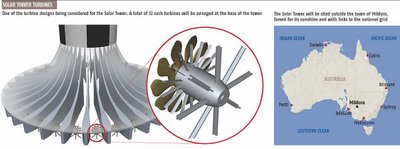

“If this concrete structure makes it off the drawing board,” the New Scientist says, “it will smash every record in the book. It will stand a staggering 1 kilometre tall, and its base will sit at the centre of a shimmering field of glass and plastic 7 kilometres across.”

So what is it?

If built, it will be “Australia’s biggest solar power plant,” a kind of chimney for hot light.

“Air heated by the sun will rise up the tower, where 32 turbines will generate about 650 gigawatt-hours of electricity a year, enough to meet the demands of 70,000 Australians.”

And if it sounds novel – it isn’t. “People have been harnessing the energy of rising columns of air for centuries,” we’re reminded.

As recently as the 1980s, for instance, a similar tower was constructed in Manzanares, Spain: “Rising 195 metres into the air and surrounded by an array of plastic sheeting 240 metres across, the Manzanares tower proved the concept worked. The plastic sunlight collector warmed the air underneath by up to 17°C, enough to draw it towards the central tower, where it created a strong enough updraught to drive a turbine and generate electricity. There were no fuel costs to pay, and no climate-damaging greenhouse-gas emissions.”

The efficiency of such a tower, we learn, “can be increased by using a larger collector to increase the air temperature at the base. And the taller the tower, the lower the ambient atmospheric pressure at the top.” This means that a “1000-metre tower will be five times as efficient as the 200-metre Manzanares tower.”

The taller the better.

Such a project is not without problems, however, “such as how to keep some 4000 hectares of greenhouse [at the foot of the tower, where the air is heated] clean enough to trap solar radiation in the first place. Legions of squeegee-wielding window cleaners will clearly not be the answer. And there are worries that the plastic sheets used to build the collector might deteriorate under the glare of the Australian sun, as they did in Manzanares.”

On the other hand, nothing is without its difficulties, and concerns of basically any kind at all are not holding back the scientists behind this and other so-called “mega-engineering” projects.

Global warming? We’ll just build huge mirrors, or use reflective balloons, to bounce all that extra solar energy back into space.

“Edward Teller,” for instance, “father of the hydrogen bomb… [once] proposed putting shards of metal or specially made ‘optical resonant scatterers’, which reflect light of particular wavelengths, into the stratosphere.”

Apparently all you’d need is “a million tonnes of tiny aluminium balloons, each around 4 millimetres across, filled with hydrogen and floated into the stratosphere… for as little as a billion dollars a year.” Not that tiny, metal balloons filled with hydrogen could interfere with wildlife, or fall into the oceans, but hey: just picture it – millions of little silver balloons floating through the stratosphere…

Installation art as climatic engineering. Or vice versa.

One wonders what else is under consideration.

How about the giant space-mirror?

Lowell Wood, at the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, wants to build “a giant diaphanous mirror in space a thousand kilometres across (!) and park it between the sun and the Earth to reflect solar radiation away from our atmosphere. Some 3000 tonnes of shield could compensate for a doubling of CO2 levels. The cost could run into hundreds of billions of dollars.”

3000 tonnes of shield – is not a phrase you read very often.

So what else could we do?

We could try “spreading billions of small reflecting objects, such as white golf balls, across the tropical oceans;” and if “golf balls and space mirrors prove to be too far-fetched, John Latham of the US government’s National Center for Atmospheric Research in Boulder, Colorado, has suggested a more down-to-earth option: making clouds whiter.”

Sounds down-to-earth to me.

But how does it work?

Latham, we read, “calculates that doubling the number of droplets in clouds over all the world’s oceans would shut down several decades of global warming. Ingeniously, he proposes doing this by deploying giant wind-powered machines” – one of which “looks rather like a giant egg whisk” – “to fling salt spray from the sea into the air.” (Incredibly, this machine was designed by a man named Salter).

“A full-size version would be 70 metres high, and hundreds of them across the oceans could whiten clouds across thousands of kilometres.”

Godzilla v. The Cloud-Salter.

Then there’s Klaus Lackner, recently featured in the Alanis Morissette-narrated “Global Warming” TV special. Lackner is a scientist at Columbia University, and he has proposed the construction of massive “forests” made from synthetic trees.

According to Lackner, each synthetic tree would look “like a goal post with Venetian blinds,” not like a tree at all.

[Image: Columbia University Earth Institute].

“But the synthetic tree would do the job of a real tree… It would draw carbon dioxide out of the air, as plants do during photosynthesis, but retain the carbon and not release oxygen.”

Each tree, as the BBC describes it, “would act like a filter. An absorbent coating, such as limewater, on its slats or ‘leaves’ would seize carbon dioxide and retain the carbon. Dr Lackner predicts that the biggest expense would be in recycling the absorber material.”

The catch is that you would need at least 250,000 of these “goal posts with Venetian blinds” studded all over the earth, located inside cities, standing like optical illusions receding over the horizon. (Smaller, domestic versions are under consideration).

In any case, all of these eco-friendly (or almost) mega-projects are barely a fraction of the actual proposals out there, passing from one desk to the next, being sent via email from one mega-engineering firm after the other, getting filed away or submitted to venture capital firms.

Yet I’m tempted to issue a call of sorts here: that any BLDGBLOG reader who gets a kick out these ideas – building artificial, carbon-absorbant forests, for instance, or the giant space-mirror (I like the tiny balloons) – should perhaps scan the classified ads each week to see if war-profiteer/engineering firms like Halliburton, Anteon, Northrop-Grumman, and their ilk are hiring.

Then get a job there, work your way to the top, and pull out of the war industries altogether.

Start building solar towers, and absorbant forests, and, while you’re at it, pump millions of dollars into modular architecture and prefab housing, not for more military training villages, but to build refugee camps and post-disaster instant cities, realizing the goals of Archigram, Greenpeace, and Architecture for Humanity, all at once.

Just a thought.

(And if you have your own mega-eco-ideas… leave a comment, below).