There are a few books I wanted to mention here at the height of the holiday season, not because they’re new or even necessarily recent but because, selfishly, I simply wish more people had read them. If you’re looking for an extra gift, or just a last-minute surprise, for anyone with an interest in architecture, landscape, archaeology, acoustics, geopolitics, history, and more, here are eight titles to consider.

(1) The Strait Gate: Thresholds and Power in Western History by Daniel Jütte (Yale University Press)—This is an academic work, in both tone and approach, but of the ideal kind: nearly every page had something I wanted to underline, write down, or scramble to look up elsewhere. Put simply, The Strait Gate is a history of the door, but, as Jütte shows, this ultra-quotidian architectural detail—the dividing line between inside and outside—has political, psychological, Constitutional, philosophical, mythological, narrative, cultural, and even material implications that are easy to overlook. Whether it’s a controversial order that “all door handles and knobs be removed from homes and shops” so that the metal could be melted down for war materiel, divine gateways as described in the Book of Revelation, or the resonant phenomenon of Torschlusspanik—“panic of gate closure,” aka a fear of being locked out—Jütte’s book is a superb example of how we can still look at architecture afresh.

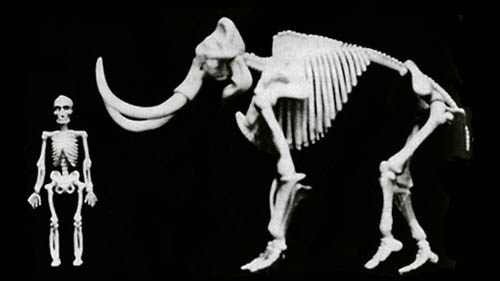

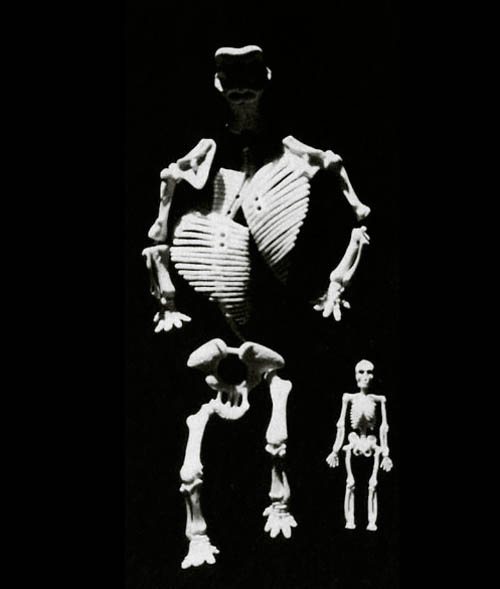

(2) The First Fossil Hunters: Dinosaurs, Mammoths, and Myth in Greek and Roman Times by Adrienne Mayor (Princeton University Press)—What did cultures without the benefit of modern scientific knowledge think of the monstrous skeletons and fossilized bones they occasionally unearthed? Quite a lot, as it happens. It turns out that huge chunks of human mythology, including the existence of dragons and the idea of an extinct race of titanic super-human ancestors, can all be traced back to misinterpretations of paleontology. Mayor’s writing is casually engaging—even quite funny, at times—and the book’s many examples of ancient human societies encountering monstrous, inexplicable, and possibly otherworldly things hidden in the earth stuck with me long after reading it.

(3) The Sound Book: The Science of the Sonic Wonders of the World by Trevor Cox (W.W. Norton)—If you have even a passing interest in sound, this is the book to read. Trevor Cox, an acoustic engineer, introduces readers to sonic phenomena around the world, both naturally occurring and artificially induced, from the frozen surface of Russia’s Lake Baikal to Stone Age tombs in rural England. There are examples of sound art, acoustic science, and even landscape-scale auditory effects that easily justify the subtitle, “sonic wonders of the world.” This would pair well with David Toop’s Ocean of Sound, for those of you interested not just in acoustics but in avant-garde composition and ambient music, as well.

(4) The Tomb of Agamemnon by Cathy Gere (Harvard University Press)—This slim book, part of classicist Mary Beard’s excellent (but, sadly, now hibernating) “Wonders of the World” series for Harvard University Press, hit so many sweet spots for me. Author Cathy Gere convincingly shows how Mediterranean archaeological discoveries over the course of the 19th century helped to shape an emerging European mythos of the glories of war and historical empire. These same emphases lent themselves extremely well, however, to tragic and grotesque distortions that soon fed into the twin ideologies of Nazism and 20th-century fascism. Along the way, Gere writes, Classical discoveries misinterpreted by modern biases helped to justify British involvement in World War I. Gere’s book includes a brief, beautiful, and monumentally sad description of young, Homer-quoting scholars being shipped off to war to fight a rising evil from the East—only to be annihilated in the sodden trenches of the Somme. The Tomb of Agamemnon is probably one of my favorite ten books of the past decade; no other book I’ve read in that time conveys the true political stakes of archaeological research and the clear and obvious risks in distorting history for ideological ends.

(5) Lawrence in Arabia: War, Deceit, Imperial Folly and the Making of the Modern Middle East by Scott Anderson (Anchor)—It’s a little disingenuous to suggest that this widely publicized book has been overlooked, but Lawrence in Arabia is nonetheless an uncannily well-timed history of the post-World War I Middle East and well worth taking the time to read. I was utterly absorbed by it for nearly a week. Part military adventure, part geopolitical biography of Lawrence of Arabia, part soul-crushing alternative history of a region that could have been—complete with agonizing descriptions of the infamous assault on Gallipoli—this book will make you see the entire 20th century differently, up to and including our own century’s Iraq War and the rise of ISIS.

(6) Map of a Nation: A Biography of the Ordnance Survey by Rachel Hewitt (Granta)—I mentioned this book in a recent post and I would recommend it again. Map of a Nation tells the story of the British Ordnance Survey, the institute’s original geopolitical context, and the experimental cartographic tools it used to make its imperial surveys more accurate. For anyone interested in geography, maps, landscape, or British history, Hewitt’s book is a must-read.

(7) Exploding the Phone by Phil Lapsley (Grove/Atlantic)—You don’t need to be interested in the wonkish details of the telephone system to be amazed by the weirdness of Exploding the Phone, Phil Lapsley’s introduction to so-called phone phreaking. On one level, it’s a story of bored teenagers using synthesized sound and DIY home electronics to hack the global telephone network; on another, it’s a story with hugely metaphoric, almost occult undertones. The phone system’s diffuse and labyrinthine system of “inward operators,” robotic mechanical test numbers, and secret military phone exchanges—to name only a few ingredients—takes on the air of something invented by Alan Moore or Grant Morrison: teens encountering a world of numerological connection and mechanical intelligence through handheld receivers in the long afternoons of the 1960s and 70s. So good.

(8) Sealab: America’s Forgotten Quest to Live and Work on the Ocean Floor by Ben Hellwarth (Simon & Schuster)—The only thing that makes me pause before recommending Ben Hellwarth’s Sealab right now is that a brand new paperback edition is due out in June 2017; but, that aside, I heartily endorse this one. Imagine Archigram teaming up with a secretive branch of the U.S. military to invent an utterly bonkers new version of human civilization on the ocean floor, and you’ve roughly pictured what this book is about. Whether it’s describing what were, in effect, moon bases at the bottom of the sea or bizarre experiments with farm animals, submerged ecological research stations or Cold War espionage in the Sea of Okhotsk, Sealab is as much outsider architectural history as it is a maritime geopolitical thriller. At the very least, preorder the forthcoming paperback if you want to wait before diving in.

Finally, it’s super-obnoxious to end with my own book, but if you’re looking for something to read this winter—or if you need a gift for someone who can be hard to shop for—consider picking up a copy of A Burglar’s Guide to the City. It’s a mix of true crime, architectural theory, and first-person reporting, from a Chicago lock-picking club to flying with the LAPD’s Air Support Division, from an architect who became the most prolific bank robber of the 19th century to fake apartments run by the British police. A Burglar’s Guide includes interviews with a Toronto burglar known for using the city’s fire code to help pick his next target, with renowned architect Bernard Tschumi, with game designers, and with FBI Special Agents, among others, and the whole thing is currently being adapted for TV by CBS Studios. Check it out, if you get the chance and let me know what you think.

[Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: From

[Image: From