it is a false and feverous state for the Centre to live in the Circumference

(Coleridge)

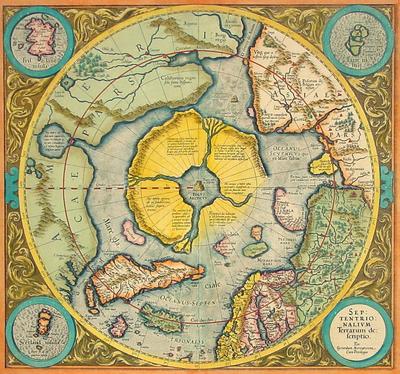

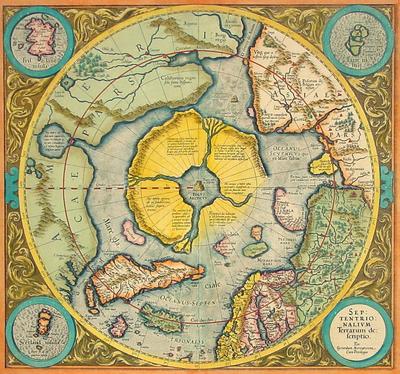

[Image: “The first map dedicated to the North Pole, by the great Gerard Mercator,” titled Septentrionalium Terrarum descriptio, reprinted 1623].

[Image: “The first map dedicated to the North Pole, by the great Gerard Mercator,” titled Septentrionalium Terrarum descriptio, reprinted 1623].

The North Pole’s melting ice cap is apparently creating something of an Arctic real estate boom.

Or a shipping route boom, more specifically: new Arctic sea channels are opening up almost literally every season, and new – or revived – ports are being opened – or renovated – to serve them.

Pat Broe, for instance, “a Denver entrepreneur,” bought a “derelict Hudson Bay port from the Canadian government in 1997” – for $7. That $7 port, however, could eventually “bring in as much as $100 million a year as a port on Arctic shipping lanes [made] shorter by thousands of miles” due to thawing sea ice.

Such Arctic routes are predicted to grow in importance quite rapidly “as the retreat of ice in the region clears the way for a longer shipping season.”

But the world is full of Pat Broes. Accordingly, “the Arctic is undergoing nothing less than a great rush for virgin territory and natural resources worth hundreds of billions of dollars. Even before the polar ice began shrinking more each summer, countries were pushing into the frigid Barents Sea, lured by undersea oil and gas fields and emboldened by advances in technology. But now, as thinning ice stands to simplify construction of drilling rigs, exploration is likely to move even farther north.”

Aside from the inevitable and ecologically unfortunate discovery of new Arctic oil reserves (“it’s the next energy frontier,” a Russian energy worker says), the “polar thaw is also starting to unlock other treasures… perhaps even the storied Northwest Passage.”

[Image: A 1754 De Fonte Map of the Northwest Passage].

[Image: A 1754 De Fonte Map of the Northwest Passage].

Something of a land grab – or sea grab – is now underway: “Under a treaty called the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, territory is determined by how far a nation’s continental shelf extends” offshore – adding a somewhat Freudian dimension to Arctic real estate. (Or perhaps we could call it the Arctic Real, where “the true coordinates are much better hidden than we realize.”)

In any case: “Under the treaty, countries have limited time after ratifying it to map the sea floor and make claims.” What kind of claims? “[C]laims of expanded territory.”

But it soon gets interesting. “In a 2002 report for the Navy on climate change and the Arctic Ocean, the Arctic Research Commission, a panel appointed by the president, concluded that species were moving north through the Bering Strait.” [Emphasis added]. Territorial alterations and geographic changes at the pole, in other words, are leading to unexpected seaborne migrations, repositionings of the planetary gene pool.

Surely there’s a James Cameron film in there, or at least some kind of Arctic pulp fiction thriller dying to be written?

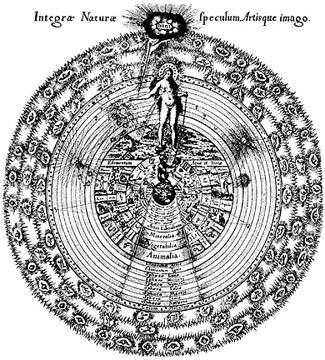

In any case, as new territories, both aquatic and terrestrial, appear at the Earth’s poles, we might do well to reconsider what Victoria Nelson calls “the Polar gothic,” or “the literary genre of mystical geography,” part of a “psychotopography” of the Earth…

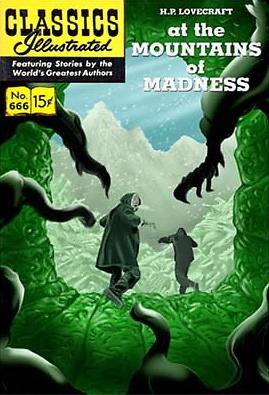

Either way I want to mention – as Nelson does – a text by H.P. Lovecraft. In his slightly goofy 1931 novella, At the Mountains of Madness, Lovecraft sends a group of geologists to the south pole where they’re meant to collect “deep-level specimens of rock and soil from the antarctic continent.” Under “great barren peaks of mystery” and “desolate summits” made of “Jurassic and Comanchian sandstones and Permian and Triassic schists, with now and then a glossy black outcropping suggesting a hard and slaty coal,” they go snowshoeing, dogsledding, and hiking some more – till, drilling through ice into the ancient metamorphic prehistory of a once-tropical antarctic mountain range, they begin “to discern new topographical features in areas unreached by previous explorers.”

Soon they find weird marine fossils.

Then ancient, apparently manmade artifacts turn up.

At night they hear things.

Then they find a city.

This antarctic city is “of no architecture known to man or to human imagination, with vast aggregations of night-black masonry embodying monstrous perversions of geometrical laws. (…) All of these febrile structures seemed knit together by tubular bridges crossing one to the other at dizzying heights,” including “various nightmare turrets,” crowding “the most utterly unknown stretches of the aeon-dead continent.” Etc.

Lovecraft’s polar gothic now continues apace, however, at the opposite end of the Earth, as the planet’s northernmost currents of melting ice bring new rivers, new migrations, and even new instant cities deep into the waters of thawing Arctic archipelagos.