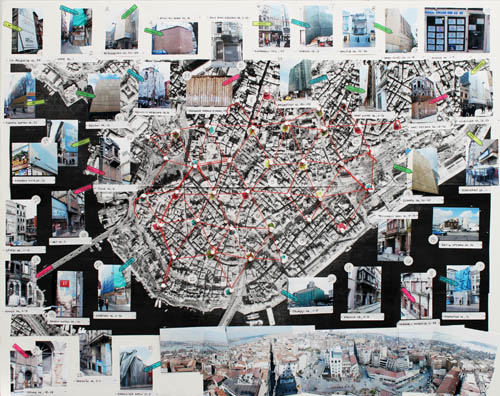

[Image: The Nesin Map by Protocol Architecture].

[Image: The Nesin Map by Protocol Architecture].

One of the more interesting student projects I’ve seen in a long time used a “document-based” approach to architecture to fabricate an entire fictional world—one in which top secret underground research labs, militarized bacteria, artificial earthquakes, and much more were all found conspiring beneath the streets of Berlin, Baghdad, and Istanbul.

A group project by three students at Columbia’s GSAPP—Yuval Borochov, Lisa Ekle, and Danil Nagy, under the guidance of professor Ed Keller—Protocol Architecture was pitched as a team that “investigates potentials for future design through the creation and analysis of hyper-fictional documents. These document sets create evidence for future scenarios that string together a specific history of political, social, and technological developments.” As such, Protocol’s work becomes less architectural than it is archival:

By focusing on the space of the document, we can avoid simplistic predictions of the future while creating a database of potential evidence which can be analyzed and interpreted by a wider audience of designers.

The resulting fictional archives—or “fabricated histories,” as the architects describe them—allowed the group to question “the role that fact and evidence plays in how we perceive our own history and our place as designers within it.”

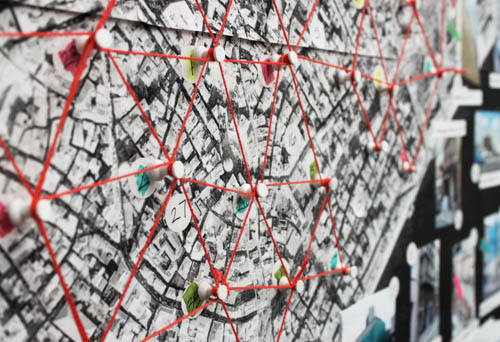

[Image: The Nesin Map (detail) by Protocol Architecture].

[Image: The Nesin Map (detail) by Protocol Architecture].

As Yuval Borochov explained to me in an email: “Protocol Architecture is a forum for investigations that challenge the traditional design process and situate every project in its own tangential line of history. We found that… the design opportunities within the plot holes of history are quite liberating. You know, I read a statement by Rem Koolhaas, in a book of his conversation with Peter Eisenman, where he explains his attempts to become the ‘architect as journalist.’ I think Protocol Architecture is akin to this mode of operation. Perhaps architects as historiographers.”

Their semester’s worth of work was remarkably varied—and mind-bogglingly prolific—and it can all be explored on their website. However, I want to focus here on three aspects of their document-based approach: The Rühmann Notebook, The Nesin Map, and The Wilbert Contracts.

Before I go much further, though, I have to say that I genuinely think this approach—and the resulting work—bears comparison to books by writers like China Miéville or Franz Kafka, even filmmakers like Guillermo del Toro, for whomever might find those coordinates intriguing. These fictional documents frame entirely self-contained imaginary worlds, and each one of these ideas deserves radical expansion elsewhere, in forms beyond architectural design; as such, they seem at least as appropriate for discussing with a literary agent as they are with the dean of an architecture school.

[Image: The Rühmann Notebook by Protocol Architecture].

[Image: The Rühmann Notebook by Protocol Architecture].

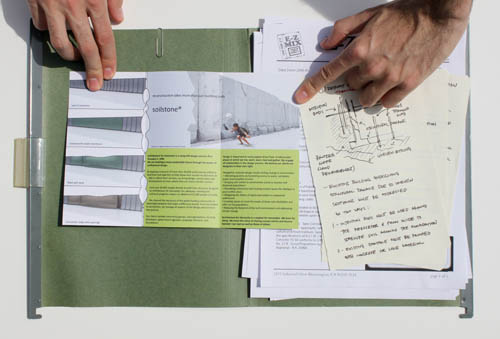

The Rühmann Notebook

The first part of Protocol Architecture’s project, the so-called Rühmann Notebook, was produced, we’re told, in early 2002 when Berliner Martina Rühmann “documented her observations of a linear pathway across former East Berlin. The path connected the Berlin Wall in the north to the wall in the south, cutting across the site of the former Palace of the Republic.”

What Rühmann’s mapping project allowed her to discover was a linear network of “small but prominent science research centers” beneath the surface of the city.

It was believed that the hidden route (subsequently discovered and documented by Rühmann) was used for communication and transfer of scientific documents and material in the 1970s and 1980s between the East and West, a time when West German scientists were making significant early discoveries in the fields of microbiology and nanotechnology.

The story here has shades of Lebbeus Woods—for instance, Woods’s ingenious proposal for a film called Underground Berlin. That film revolves around a disillusioned architect, a missing twin brother, neo-Nazi activities in the divided city of Berlin, metallic underground tunnels connecting east to west, and “a top-secret underground research station rumored to be somewhere beneath the very center of Berlin.” There are even rogue planetary scientists investigating “tremendous, limitless geological forces active in the earth.”

In any case, Rühmann’s labs, we learn, were studying bacterial technologies—specifically the use of Bacillus Pasteurii, “a bacteria with adhesive qualities… to stabilize ground in earthquake-prone cities,” and Shewanella, “a bacteria capable of naturally producing electrically conductive nano-tube filaments, now able to produce nano-electric devices.” The architectural implications of these bacterial species begin to loom large in the overall narrative. (If you like the sound of this, by the way, don’t miss Magnus Larsson’s work, featured here on BLDGBLOG in April 2009, or our earlier look at geobatteries).

The locations of these underground biotechnological seismology research labs are what we see documented in the The Rühmann Notebook. The “notebook” itself consists of photos and notes collaged inside a Moleskine.

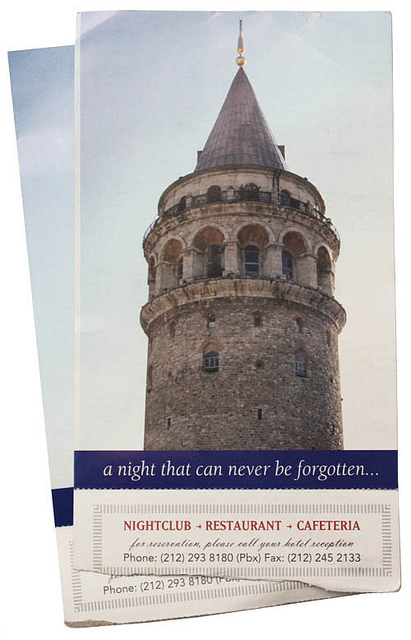

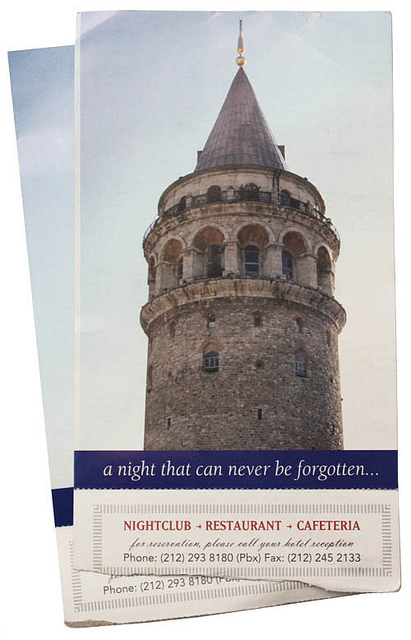

[Image: Istanbul’s Galata Tower, as depicted on ephemera related to The Nesin Map by Protocol Architecture].

[Image: Istanbul’s Galata Tower, as depicted on ephemera related to The Nesin Map by Protocol Architecture].

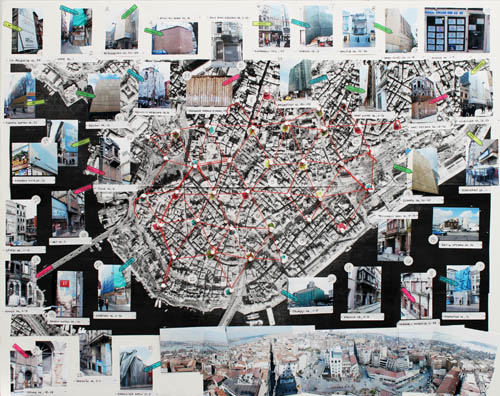

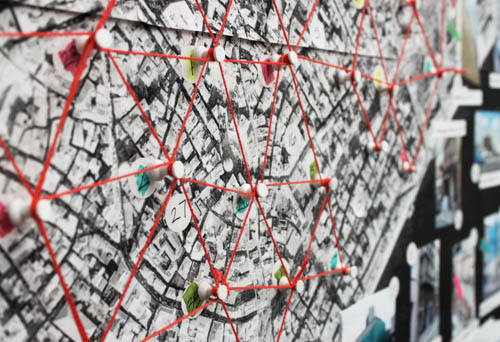

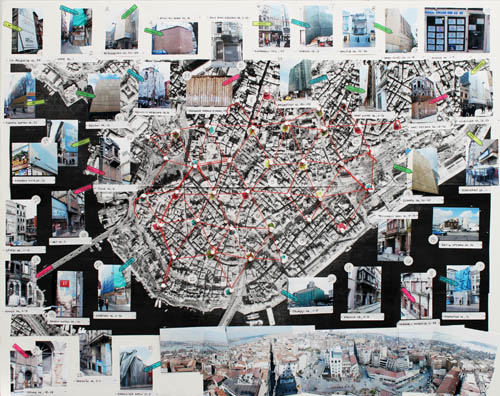

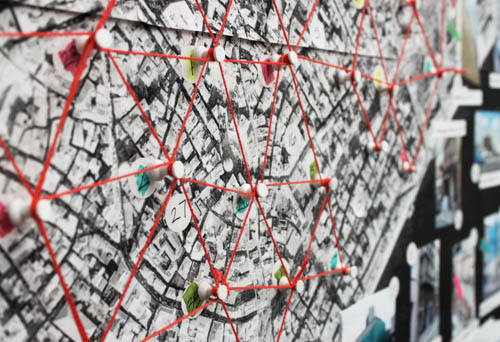

The Nesin Map

We now move from Berlin to Istanbul, where The Nesin Map documents a seemingly unrelated network of “concealed buildings” in the city:

Harem Nesin, a Turkish journalist for the Istanbul newspaper Dünya Gazetesi, began photographing concealed buildings in Istanbul sometime in 2017 for his personal records. The buildings captured by Nesin had recently been destroyed by a fire or evacuated due to some other instability of the structure, and were later covered by scaffolding, tarps, or screens. Nesin correlated his collection of photographs to a map of Istanbul, indicating the location of each abandoned building. Through the mapped locations Nesin discovered a triangular geometric pattern across a portion of the city on the European side, from the Golden Horn to the Bosphorus. Nesin used the Galata Tower as a place to survey the buildings in question, indicated by his collage of aerial photographs taken from the Tower. Additionally, in his observations Nesin recorded the means of concealment (tarp, wood, fence, screen) and the address for each structure.

First of all, this is an amazing set-up for a story, somewhere between Borgesian urban paranoia and Debordian psychogeography; and, second, the map itself is very, very cool. Here are the two images of it again.

[Images: The Nesin Map by Protocol Architecture].

[Images: The Nesin Map by Protocol Architecture].

So what did Nesin discover as he correlated his data and began to map it all out? A diagrid of “injection points” located at geologically precise points around Istanbul: “Harem Nesin’s map reveals strategic locations used by the Istanbul Metropolitan Municipality as injection points for Bacillus Pasteurii, a microbe able to transform sand into sandstone by depositing calcite (calcium carbonate) throughout the granules, fusing them together.”

The authorities, in other words, were earthquake-proofing the city from below, in “the first application of the bacteria, which had been under development since the mid 1970s through joint research between Germany and the US.”

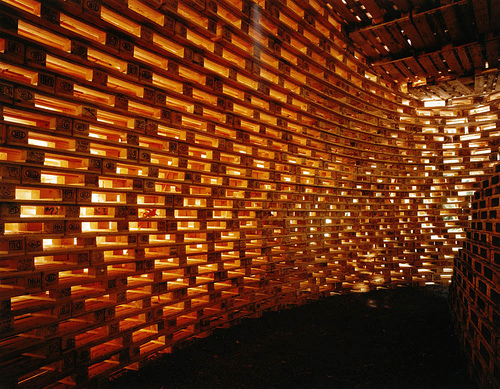

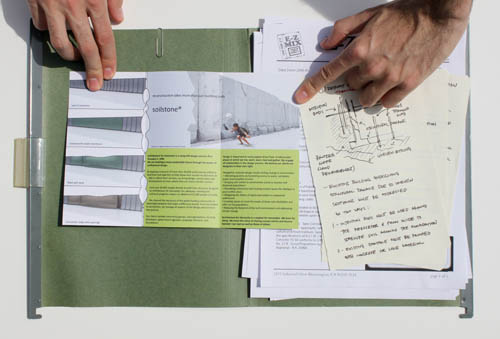

The Wilbert Contracts

Finally, to Baghdad. The The Wilbert Contracts are a series of files tracing the work of John Wilbert and Co., a quasi-military subcontractor working on a project for Monsanto “between the years 2028 and 2031” in Iraq. Monsanto’s SoilStone® initiative used soil-stabilization biotechnologies to replace concrete walls with more flexible barriers, such as elastic membranes and bacterially-activated sand (i.e. SoilStone®).

[Images: The Wilbert Contracts by Protocol Architecture].

[Images: The Wilbert Contracts by Protocol Architecture].

We learn, however, that “linear connections can be perceived” between the multiple sites at which Wilbert and Co. used this technology—indeed, “certain documents from the US Army which are still classified imply that underground tunnel systems were dug between 2028 and 2030.”

It is further inferred, the architects explain, that “pre-programmed nano-bots” were being used in the project as construction machines, selectively injecting Bacillus Pasteurii bacteria into the sands. This technique thus created a semi-mobile, makeshift system of subterranean spaces through which the US military could move. The Army is down there, in other words, stabilizing classified tunnels beneath the streets.

[Images: From Berlin 2050 by Protocol Architecture].

[Images: From Berlin 2050 by Protocol Architecture].

In the end, after a fascinating internal design competition that I simply don’t have the time to cover here—with a jury that included Reza Negarestani of Cyclonopedia fame and Jamie Kruse of smudge studio, among many others, and with entries that ranged from sentient clouds of nano-flies to stabilized earthquakes as a form of urban planning—the group assembled all of their ideas into a proposal for underground spaces in Berlin. These final proposals, however, as well-rendered as they are, simply don’t hold the imaginative appeal for me that the earlier studio material all but burns with.

And that’s the rub: at the end of the day, most architecture students—unsurprisingly—think they have to take this stuff, put it all together, and produce something clearly definable as a building. But the research, in many cases, is more worthy of attention (and well worth the time it takes to produce it). In other words, the research—the preliminary material, the periphery, the narrative excess, the unwanted fringe—is very often most provocative before it becomes a building, when that inchoate mass of possible future projects, storylines, techniques, and more offers a million alternative directions in which we have yet to go.

[Image: The Wilbert Contracts by Protocol Architecture].

[Image: The Wilbert Contracts by Protocol Architecture].

I only say this here because it is extraordinarily exciting to see a project like this, that out-fictionalizes the contemporary novel and even puts much of Hollywood to shame—to realize, once again, that architecture students routinely trade in ideas that could reinvigorate the film industry and the publishing industry, which is all the more important if the world of private commissions and construction firms remains unresponsive or financially out of reach. The Nesin Map alone, given a screenwriter and a dialogue coach, could supply the plot of a film or a thousand comic books—and rogue concrete mixtures put to use by nefarious underground militaries in Baghdad is an idea that could be optioned right now for release in summer 2013. HBO should produce this immediately.

My point is not that architecture students should somehow be expected to stop doing the very thing they are in school for—i.e. to learn how artificial enclosures are designed and constructed. I just mean that they should never overlook the interest of their own preliminary ideas, notes, sketches, and scenarios. After all, with just a well-timed email or elevator pitch, all of that stuff—all those bulletin boards, browser tabs, sketchbooks, notes from late-night conversations, site maps, and more—needn’t become just more crap to get filed away in your parents’ house somewhere, but could actually be turned into the seed of a film, novel, game, or comic book in another cultural field entirely.

Don’t give up on your ideas—and don’t overlook the value of something simply because it can’t be turned into a building.

Check out Protocol Architecture’s work in their own words—and with many more images—over on their website. And consider supporting the trio by purchasing their book on Lulu.

(Thanks to Ed Keller for inviting me to see Protocol Architecture’s work as a guest critic).

[Image: “Storm Clouds Over Central Park” by Joseph Bergantine].

[Image: “Storm Clouds Over Central Park” by Joseph Bergantine]. [Image: Hurricane Katrina approaches New Orleans—possibly attracted there, a new study suggests, by the “rough cityscape” of the greater metropolitan region].

[Image: Hurricane Katrina approaches New Orleans—possibly attracted there, a new study suggests, by the “rough cityscape” of the greater metropolitan region]. [Image: Hurricane Isabel seen from space].

[Image: Hurricane Isabel seen from space].

[Image: The

[Image: The  [Image: The

[Image: The  [Image: The

[Image: The

[Images: The

[Images: The  [Images: The

[Images: The

[Image: Detailed view of

[Image: Detailed view of  [Image: Detail from

[Image: Detail from  [Image: Detail from

[Image: Detail from  [Image: Detail from

[Image: Detail from  [Image: NASA/KSC

[Image: NASA/KSC

[Image: Photo by Ricardo DeAratanha, courtesy of the

[Image: Photo by Ricardo DeAratanha, courtesy of the

[Image:

[Image:

[Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: From

[Image: From

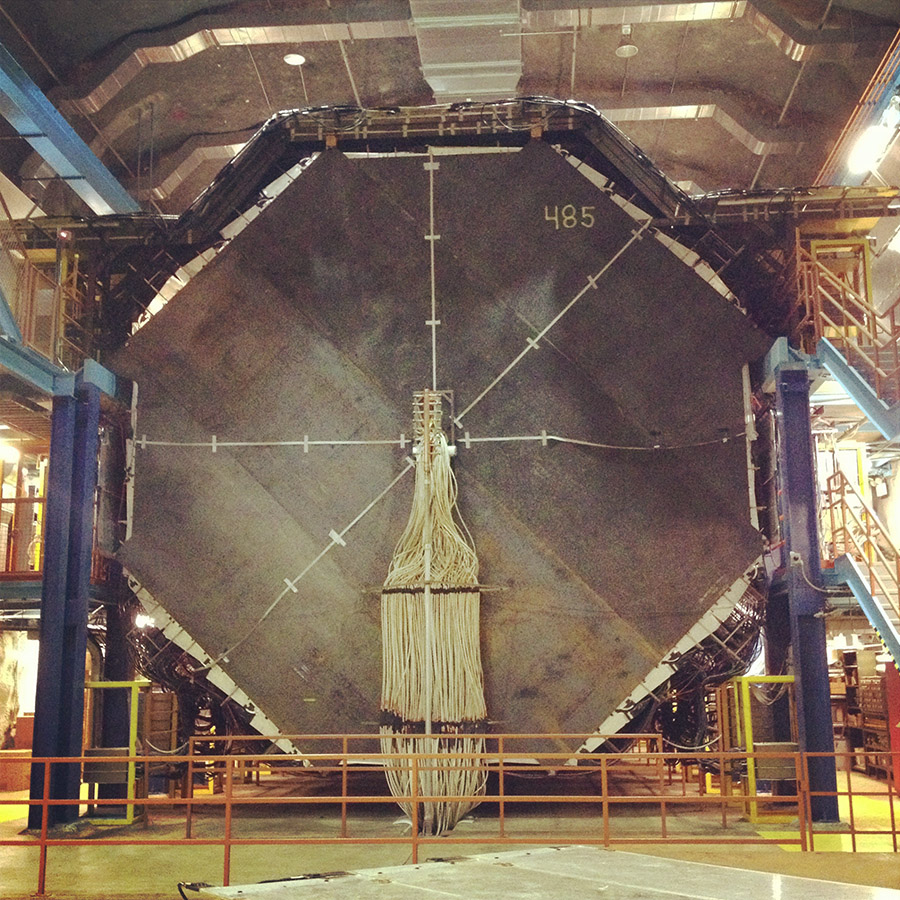

[Image: The 5,000-ton neutrino detector of the

[Image: The 5,000-ton neutrino detector of the  [Image: The subterranean domestic furnishings of the

[Image: The subterranean domestic furnishings of the  [Image: At the headwaters of the Mississippi River in

[Image: At the headwaters of the Mississippi River in  [Image: Hiking the

[Image: Hiking the  [Image: Butte, Montana’s

[Image: Butte, Montana’s

[Image:

[Image:  [Image:

[Image:  [Image:

[Image:  [Image: Istanbul’s Galata Tower, as depicted on ephemera related to

[Image: Istanbul’s Galata Tower, as depicted on ephemera related to

[Images:

[Images:

[Images: From

[Images: From  [Image:

[Image:

[Image: U.S./Mexico border marker #184; photograph by

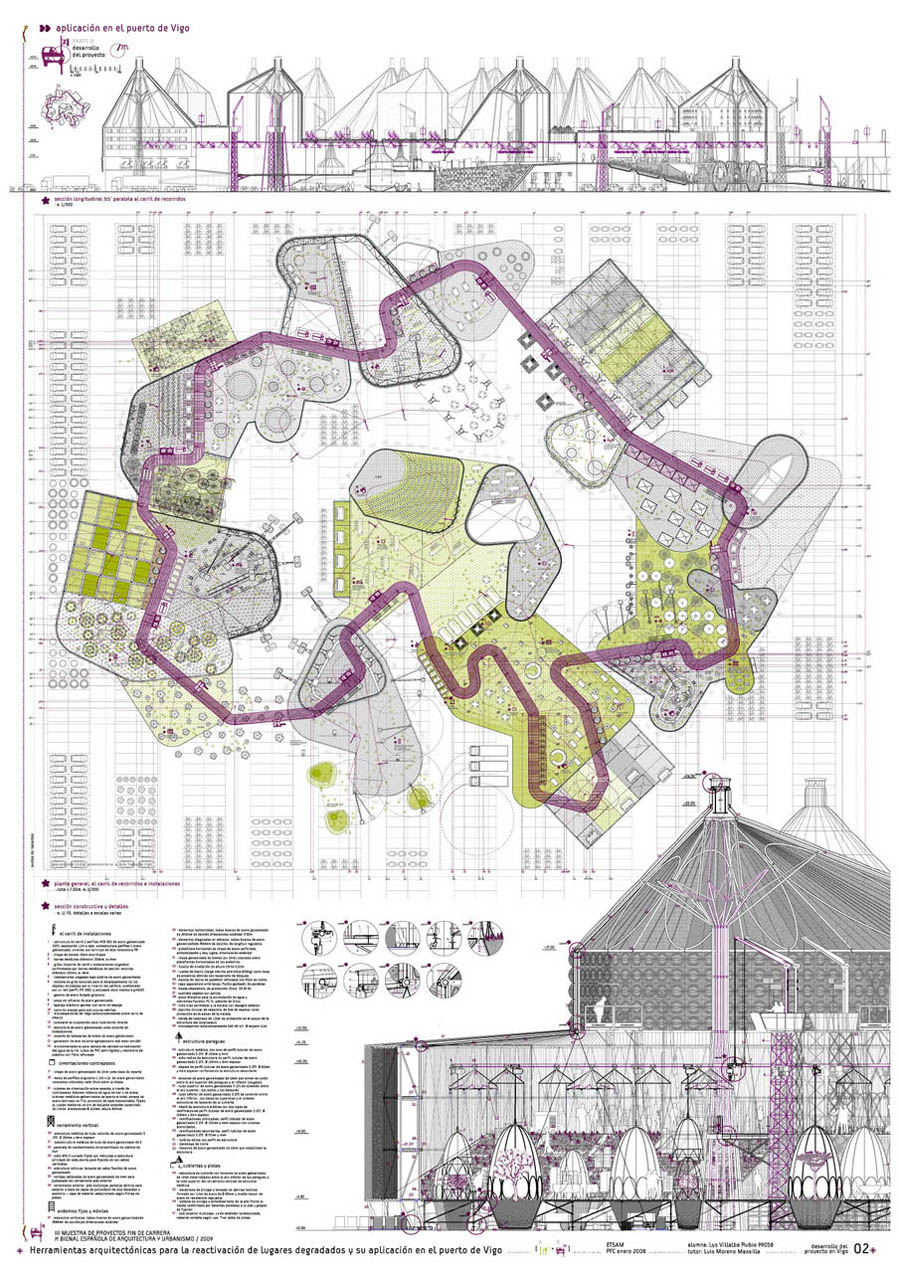

[Image: U.S./Mexico border marker #184; photograph by  [Image: From a project by Lys Villalba Rubio].

[Image: From a project by Lys Villalba Rubio]. [Image: From a project by Lys Villalba Rubio].

[Image: From a project by Lys Villalba Rubio].