[Note: This post was originally written for Blend – so it reads a bit like an article – though it was not actually published].

[Note: This post was originally written for Blend – so it reads a bit like an article – though it was not actually published].

The company known as Muzak claims to provide “audio architecture” for its clients.

Audio architecture may sound wonderful; the phrase may conjure up images of cathedrals made from noise – whole buildings connected by bridges of music – but, in the world of Muzak, it means something less exciting. Audio architecture, Muzak writes, is “the integration of music, voice and sound to create experiences designed specifically for your business.”

In other words, audio architecture is about making you feel comfortable – so that someone else can sell you things.

The “power” of audio architecture, Muzak‘s website continues, “lies in its subtlety.” These subtle sounds, played incessantly in the background, can “bypass the resistance of the mind and target the receptiveness of the heart.” It is thus almost literally subliminal. “When people are made to feel good in, say, a store, they feel good about that store. They like it,” Muzak claims. “Audio architecture builds a bridge to loyalty. And loyalty is what keeps brands alive.”

If there is a connection between background sounds and customer loyalty, perhaps sound could also inspire a kind of urban loyalty, where the sound of a certain city plays its own subtle role in making that place more inhabitable.

Like Muzak, the city’s sound makes residents “feel good” – which “builds a bridge to [urban] loyalty.”

Of course, this would not be the first time someone has suggested that cities have a certain sound, unique to them, or that cities should learn to cultivate their unique sonic qualities.

Of course, this would not be the first time someone has suggested that cities have a certain sound, unique to them, or that cities should learn to cultivate their unique sonic qualities.

More than thirty years ago, the World Soundscape Project called for the “tuning” of the world. Cities would be treated as vast musical instruments: certain sounds would be eliminated altogether; others would be promoted or even subtly redesigned. The World Soundscape Project was about sonic improvement, making the world sound better, one city – one building – at a time.

Where the Project went wrong, however, and where it began to act a bit like Muzak, was when it thought it had a kind of sonic monopoly over what sounded good. Industrial noises would be scrubbed from the city, for instance, and a nostalgic calm would be infused in its place. Think church bells, not automobiles.

But where would such sensory cleansing leave those of us who enjoy the sounds of factories…?

In any case, we could still have fun with the World Soundscape Project, designing alternative sonic futures for the cities of the world, by turning, ironically, to the techniques of Muzak itself: Muzak imitates. Rock, jazz, blues, Mozart – even Muzak: anything at all can be absorbed, and replaced, and reproduced, by Muzak.

There could be a Muzak version of the street sounds of Amsterdam – played on a continuous loop in the supermarkets of London. The sounds of yesterday could be replayed today, transformed into Muzak – and Muzak versions of your old phone conversations could be broadcast over the radio… where laughter is replaced with synthesizer trills.

University lectures and Books on Tape could be replaced with Muzak, pushing us toward a post-verbal society.

Or we forget Muzak altogether and we simply swap urban soundtracks, cities imitating cities to sound entirely unlike themselves.

In the elevators of the Empire State Building, you hear the elevators of the Eiffel Tower. The sounds of the Paris Metro are replaced with the sounds of the Beijing subway, complete with squeals from overworked brakes and the metallic thud of sliding doors.

If you don’t like Rome, you can make it sound like Dubai.

In his 1964 novel Nova Express, William Burroughs described a series of elaborate, even hallucinatory, assemblages of tape recorders and microphones that could be carried from city to city.

In his 1964 novel Nova Express, William Burroughs described a series of elaborate, even hallucinatory, assemblages of tape recorders and microphones that could be carried from city to city.

Borderless, these roving sound installations, with their capacity for instant playback, would blur the line between your own thought processes and the sounds of the city around you. Like Muzak, Burroughs’s legion of rogue microphonists could thus “bypass the resistance of the mind,” installing a soundtrack where there once had been thought.

A few years ago I read about a sound artist who had been reproducing the exact placement of microphones used to record the live performances of orchestras around the world, only he did so in unexpected places: in the middle of rain forests, or on top of sand dunes, or in towns on the English coast and inside empty warehouses.

Whether or not the story’s even true, recording the everyday noises of, say, Oslo as if Oslo is an ongoing symphony – and then re-playing that symphony through hidden speakers in San Francisco – perhaps even transforming it into Muzak – should certainly be the next artistic step.

It would be a question of acoustic urban design – of true audio architecture.

(Earlier on BLDGBLOG: Cover Bands of Space and Amplifier House: Original Domestic Soundscapes. See also AUDC’s The Stimulus Progression).

The manifestos that I posted about

The manifestos that I posted about  and a press release by

and a press release by  About twenty minutes after writing the previous post, I felt my

About twenty minutes after writing the previous post, I felt my  [Image: Bolivia’s

[Image: Bolivia’s  [Image: Photo by Allen Brisson-Smith for

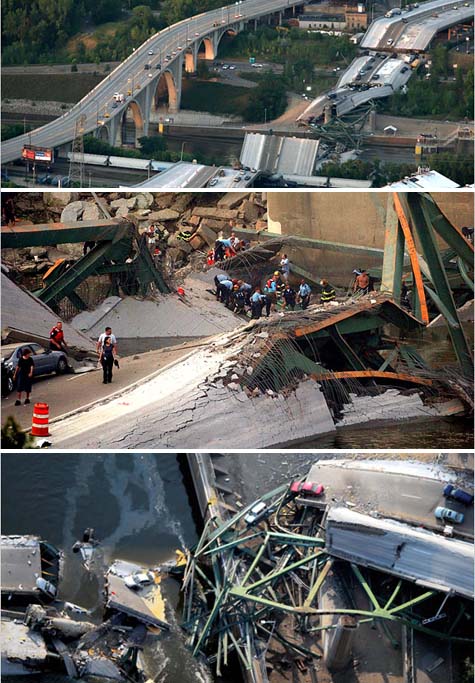

[Image: Photo by Allen Brisson-Smith for  [Image: Photo by Jeff Wheeler/The Star Tribune/AP; via

[Image: Photo by Jeff Wheeler/The Star Tribune/AP; via  [Image: Photo by Heather Munro/The Star Tribune/AP; via

[Image: Photo by Heather Munro/The Star Tribune/AP; via  [Images: Photos courtesy of

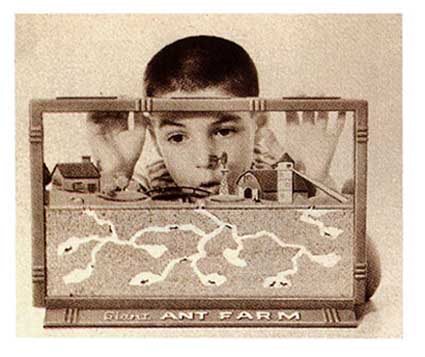

[Images: Photos courtesy of  Future Australians perplexed by the design of their cities might have ants to blame: “The movement of ants could help solve traffic jams and crowd congestion, Australian scientists say, and the findings could be used in

Future Australians perplexed by the design of their cities might have ants to blame: “The movement of ants could help solve traffic jams and crowd congestion, Australian scientists say, and the findings could be used in  [Image: The cover of

[Image: The cover of  [Image: Some page-spreads from

[Image: Some page-spreads from  [Images: Cacti at the Huntington Library in Pasadena].

[Images: Cacti at the Huntington Library in Pasadena]. [Image: Cacti at the Huntington Library in Pasadena].

[Image: Cacti at the Huntington Library in Pasadena]. [Image:

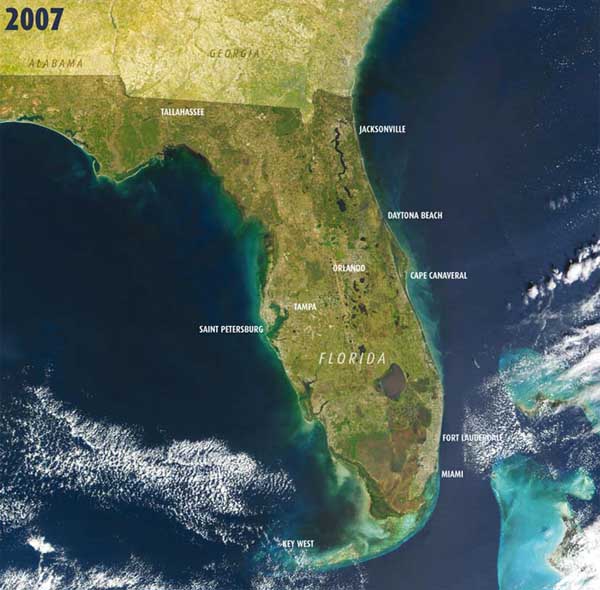

[Image:  [Image: Florida in 2007; via

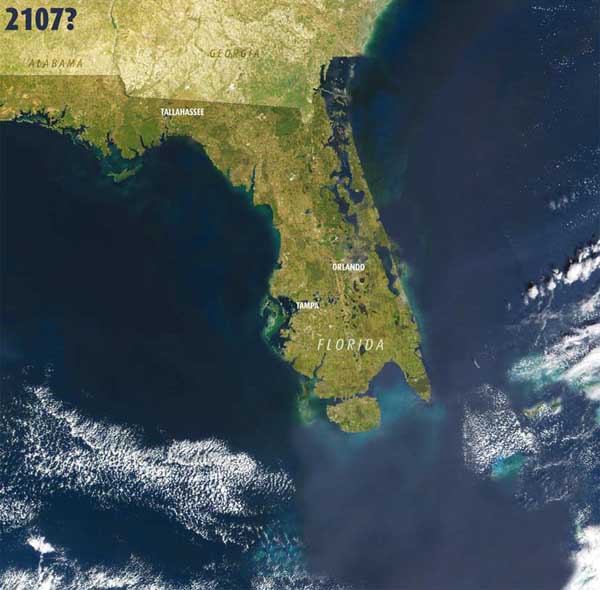

[Image: Florida in 2007; via  [Image: Florida in 2107; via

[Image: Florida in 2107; via  [Image: Northwestern Europe in 2107; via

[Image: Northwestern Europe in 2107; via  [Image: A thoughtfully signposted British flood; photo by Matt Cardy for Getty Images].

[Image: A thoughtfully signposted British flood; photo by Matt Cardy for Getty Images]. [Image: The Tewkesbury flood of 2007, as seen from the air; photo by Daniel Berehulak for Getty Images].

[Image: The Tewkesbury flood of 2007, as seen from the air; photo by Daniel Berehulak for Getty Images]. Calculated to stop the hearts of English people the world over, those maps show us a land-bridge, continentalizing Kent, putting Franco in the Anglo and de-Saxonizing the island from its royal isolation. And I have no idea what that sentence means, either.

Calculated to stop the hearts of English people the world over, those maps show us a land-bridge, continentalizing Kent, putting Franco in the Anglo and de-Saxonizing the island from its royal isolation. And I have no idea what that sentence means, either.  [Image: A slightly more accurate map of both the chalk ridge and the glacial lake it held back; via the

[Image: A slightly more accurate map of both the chalk ridge and the glacial lake it held back; via the  [Image: The Tewkesbury flood of 2007, as seen from the air; photo by Daniel Berehulak for Getty Images].

[Image: The Tewkesbury flood of 2007, as seen from the air; photo by Daniel Berehulak for Getty Images]. [Image: Artist/photographer unknown. From an old post on

[Image: Artist/photographer unknown. From an old post on