[Image: The Key Lake uranium mine].

I’m in the process of finishing Tom Zoellner’s new book Uranium, and I’m finding it extremely hard to put down. A beautifully written history of the radioactive mineral used in nuclear weapons, it includes some amazing anecdotes and descriptions.

What’s particularly interesting about the book, however, as least for me, is that it very firmly locates nuclear weapons as geological devices. That is, atomic bombs are both of and from rocks—they are mineralogy pursued to its most explosive ends, metals transformed into “mammoth amounts of energy,” able to level cities and mountains both.

Indeed, uranium, Zoellner writes, is “the mineral of apocalypse.” There is “a fearsome animal caged in this exotic metal,” he writes, “hot as the sun, but one whose instabilities could be accurately charted and precisely aimed.”

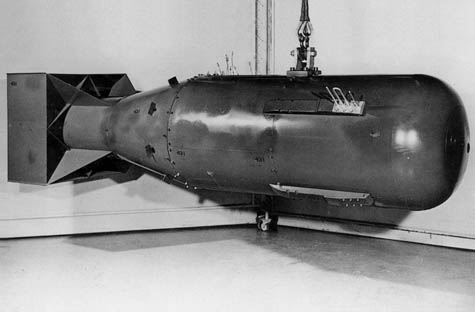

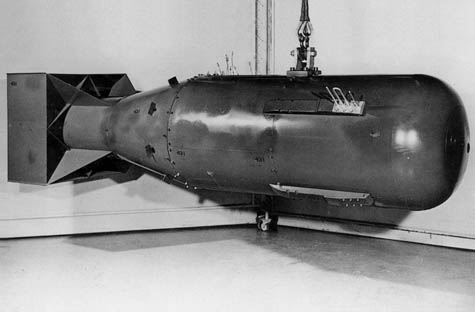

[Image: The uranium-powered Fat Man bomb].

There is a moment in John Milton’s Paradise Lost, which I mention in The BLDGBLOG Book, where Milton—writing in the 1600s—describes mineral weaponry pulled from the surface of the earth by Satan’s minions as they launch an insurrectionary terrorist assault on God. It is geological siege-warfare, we might say.

Milton describes, in Book Six, “materials dark and crude” located “deep under ground”; they “shoot forth / So beauteous, opening to the ambient light” when illuminated by “Heaven’s ray.” These crude materials, Milton writes, are then rammed down into cannons to form long-range weaponry:

These in their dark nativity the deep

Shall yield us, pregnant with infernal flame;

Which, into hollow engines, long and round,

Thick rammed, at the other bore with touch of fire

Dilated and infuriate, shall send forth

From far, with thundering noise, among our foes

Such implements of mischief, as shall dash

To pieces, and o’erwhelm whatever stands

Adverse, that they shall fear we have disarmed

The Thunderer of his only dreaded bolt.

While I’m aware that this is simply a poetic extrapolation from existing technologies of the time—i.e. the “dilated and infuriate” energy of gunpowder—Paradise Lost has the often uncanny feeling of being a description of militararized uranium three centuries in advance of the Manhattan Project.

At one point, Zoellner himself refers to uranium as “a mineral demon,” bringing to mind Milton’s Pandemonium—that is, the place of all demons.

[Image: The weaponization of geology in the form of the Little Boy atomic bomb].

In any case, Zoellner’s book is full of incredible descriptions. For instance, “Testing [uranium-fueled nuclear weapons] at the Nevada Proving Ground has revealed that a nuclear bomb buried in a deep shaft underneath a mountain would vaporize the surrounding rock and make a huge cathedral-like space inside the earth, ablaze with radioactivity.”

Or take Zoellner’s short history of something called Project GNOME, which experimentally deployed a small atomic bomb underground in New Mexico in order to see if its detonation could flash-vaporize groundwater, providing steam for a subterranean power plant.

[Image: Inside the underground chamber created by the Project GNOME explosion].

The “muffled bang” of this experiment produced an extraordinary false geology:

When workers tunneled in more than half a year later to inspect the damage, they found a hollow chamber about the size of the U.S. Capitol dome. The rock walls were colored brilliant shades of blue, green, and purple and bore an angry surface temperature of 140 degrees Fahrenheit. Drilling at the site is prohibited today; the radiation still poses a danger.

Architectural metaphors come easily to Zoellner, and he makes good, illustrative use of specific buildings; who knew the Monadnock Building in Chicago could serve as a metaphor for the structure of uranium?

The Monadnock was stone and mortar, and sixteen stories was the breaking point with those materials. Any higher and the whole thing would fall into a pile of rubble, or require walls so big and windows so small that the rooms would have resembled dungeon cells… The building is so obese with masonry that it sank nearly two feet into Chicago’s lakefront soil after it opened. It is still the tallest building in the world without a steel frame, and it represents a monument of sorts: the very brink of physical possibility…

There is a similar invisible limitation inside atoms, and uranium is the groaning stone skyscraper among them, pushing the limits of what the universe can tolerate and tossing away its bricks in order to forestall a total collapse. This is radioactivity.

There is one more longish quotation I want to draw attention to. The middle-third of the book is about the uranium rush that erupted in the American southwest in the 1950s; uranium, far from being rare in nature, was found at a wide range of sites, including near the town of Moab, Utah.

[Image: Yellowcake uranium].

In the Book of Zephaniah, Zoellner points out, no less a figure than God refers to a settlement called Moab, saying it is “a place of weeds and salt pits, a wasteland forever.” That a town in Utah might name itself this is either self-deprecation at its most extraordinary or an unfortunate error (indeed, Zoellner mentioned that the town tried, unsuccessfully, to rename itself for several decades).

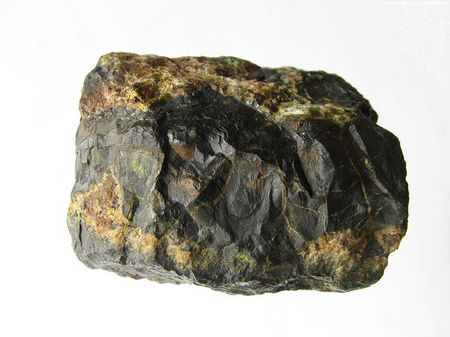

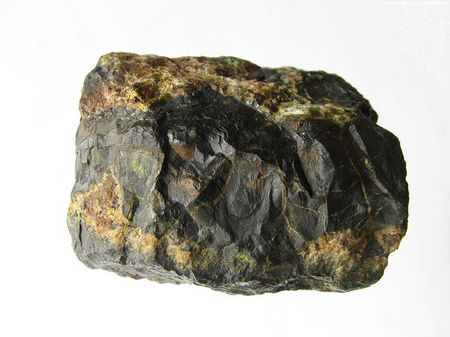

[Image: Pitchblende, via Wikipedia].

What’s fascinating, though, is that uranium was not hard to come by out there; indeed, one could often find these chromosome-mutating, highly radioactive rocks literally just sitting on the surface of the desert, sometimes shining yellow in the arid sunlight. I was thus blown away by a passing comment Zoellner makes when he describes the scabbed desert cliffs, canyons, and hills within which American uranium was found:

In the shaded alcoves of some of the cliffs, a race of Indians called the Anasazi had left paintings of gazelles and misshapen humans: the people themselves had vanished in the thirteenth century.

Pictures of misshapen humans. This is clearly something for anthropologists and art historians to discuss, but how absolutely extraordinary to consider the possibility that depictions of humanoid forms in Anasazi rock art were not, in fact, fantastic depictions of mythological figures or a creative exploration of the human anatomy—a desert Demoiselles d’Avignon six hundred years before Picasso—but realistic depictions of people mutated by the rocks around them.

I could go on at great length; Uranium is a fascinating book, and, as I mentioned, it takes several steps in the direction of what I might call a geological history of the atomic bomb (something I would love to read or write).

[Image: Abandoned pit of the Mary Kathleen uranium mine, Queensland, Australia; via Wikipedia].

But I was also specifically reminded of the book when I read last night that 10% of the U.S. power grid is fueled by dismantled nuclear warheads—including many purchased from the former Soviet Union.

“Salvaged bomb material now generates about 10 percent of electricity in the United States,” the New York Times reports; “by comparison, hydropower generates about 6 percent and solar, biomass, wind and geothermal together account for 3 percent. Utilities have been loath to publicize the Russian bomb supply line for fear of spooking consumers: the fuel from missiles that may have once been aimed at your home may now be lighting it.” As one consultant interviewed in the article quips: “‘You can look at it like a couple of very large uranium mines,’ he said of the fissile material that would result from the program.”

Known officially as the Megatons to Megawatts program, it comes with the poetic implication that any forensic dissection of the U.S. national power grid would eventually come up against mineral remnants of Cold War Soviet weaponry. Ticking away somewhere inside the infrastructure of the United States is the radioactive dust of an undeclared nuclear war.

It also makes one wonder what John Milton might do with the U.S. electrical grid—what mythic scenes of electrical warfare, fueled by repurposed missiles and clouds of fallout, he would describe being unleashed upon the scarred bedrock of continents.

But, even at its most mundane, this is stunning: it’s as if, on the one hand, we have Hoover Dam, spinning its turbines and sending power to the people of the American southwest, and, on the other, we have an unlocked stockpile of old weapons, like some strange archaeological site, fizzing down somewhere in a power plant, generating light for our cities.

[Image: Azadi Tower in Tehran’s Azadi Square].

[Image: Azadi Tower in Tehran’s Azadi Square]. [Image: “Aqualta: 5th Avenue & 35th Street, NYC,” by

[Image: “Aqualta: 5th Avenue & 35th Street, NYC,” by  [Image: “Aqualta: Garment District, NYC,” by

[Image: “Aqualta: Garment District, NYC,” by

[Images: “

[Images: “ [Image: “Aqualta: Shibuya Station, Tokyo,” by

[Image: “Aqualta: Shibuya Station, Tokyo,” by  [Image: “Aqualta: 5th Avenue & 53rd Street, NYC,” by

[Image: “Aqualta: 5th Avenue & 53rd Street, NYC,” by  [Image: A map of pilot-reported turbulence above the U.S. east coast].

[Image: A map of pilot-reported turbulence above the U.S. east coast]. [Images: From

[Images: From

[Image: London’s

[Image: London’s  [Image: Planetarium projection equipment].

[Image: Planetarium projection equipment]. [Image: From a review of David Wright’s

[Image: From a review of David Wright’s  [Image: A flood strikes Manhattan; image via

[Image: A flood strikes Manhattan; image via  [Image: The multiple-shadow casting cube by

[Image: The multiple-shadow casting cube by  [Image: A diagram of landslide dynamics—how surfaces seek out and reassert equilibrium—courtesy of the

[Image: A diagram of landslide dynamics—how surfaces seek out and reassert equilibrium—courtesy of the  [Image: A

[Image: A  [Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: From the film

[Image: From the film