You might have seen the news last month that two students from George Mason University developed a way to put out fires using sound.

“It happens so quickly you almost don’t believe it,” the Washington Post reported at the time. “Seth Robertson and Viet Tran ignite a fire, snap on their low-rumbling bass frequency generator and extinguish the flames in seconds.”

Indeed, it seems to work so well that “they think the concept could replace the toxic and messy chemicals involved in fire extinguishers.”

There are about a million interesting things here, but I was totally captivated by two points, in particular.

At one point in the video, co-inventor Viet Tran suggests that the device could be used in “swarm robotics” where it would be “attached to a drone” and then used to put out fires, whether wildfires or large buildings such as the recent skyscraper fire in Dubai. But consider how this is accomplished; from the Washington Post:

The basic concept, Tran said, is that sound waves are also “pressure waves, and they displace some of the oxygen” as they travel through the air. Oxygen, we all recall from high school chemistry, fuels fire. At a certain frequency, the sound waves “separate the oxygen [in the fire] from the fuel. The pressure wave is going back and forth, and that agitates where the air is. That specific space is enough to keep the fire from reigniting.”

While I’m aware that it’s a little strange this would be the first thing to cross my mind, surely this same effect could be weaponized, used to thin the air of oxygen and cause targeted asphyxiation wherever these robot swarms are sent next. After all, even something as simple as an over-loud bass line in your car can physically collapse your lungs: “One man was driving when he experienced a pneumothorax, characterised by breathlessness and chest pain,” the BBC reported back in 2004. “Doctors linked it to a 1,000 watt ‘bass box’ fitted to his car to boost the power of his stereo.”

In other words, motivated by a large enough defense budget—or simply by unadulterated misanthropy—you could thus suffocate whole cities with an oxygen-thinning swarm of robot sound systems in the sky. Those “Ride of the Valkyries”-blaring speakers mounted on Robert Duvall’s helicopter in Apocalypse Now might be playing something far more sinister over the battlefields of tomorrow.

However, the other, more ethically acceptable point of interest here is the possible landscape effect such an invention might have—that is, the possibility that this could be scaled-up to fight forest fires. There are a lot of problems with this, of course, including the fact that, even if you deplete a fire of oxygen, if the temperature remains high, it will simply flicker back to life and keep burning.

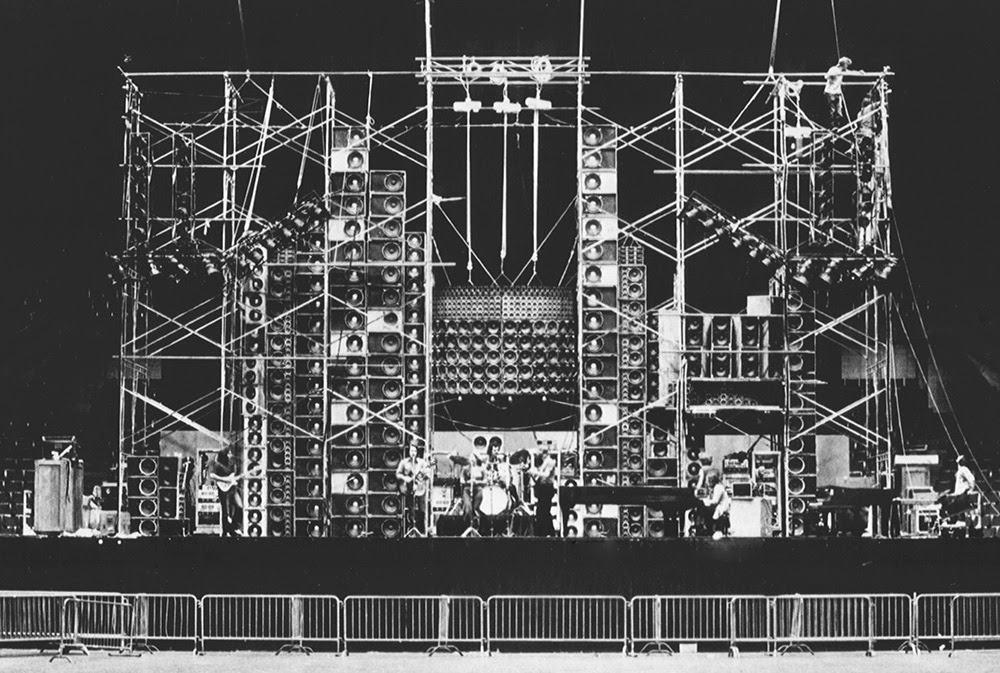

[Image: The Grateful Dead “wall of sound,” via audioheritage.org].

[Image: The Grateful Dead “wall of sound,” via audioheritage.org].

Nonetheless, there is something awesomely compelling in the idea that a wildfire burning in the woods somewhere in the mountains of Arizona might be put out by a wall of speakers playing ultra-low bass lines, rolling specially designed patterns of sound across the landscape, so quiet you almost can’t hear it.

A hum rumbles across the roots and branches of burning trees; there is a moment of violent trembling, as if an unseen burst of wind has blown through; and then the flames go out, leaving nothing but tendrils of smoke and this strange acoustic presence buzzing further into the fires up ahead.

Instead of emergency amphibious aircraft dropping lake water on remote conflagrations, we’d have mobile concerts of abstract sound—the world’s largest ambient raves—broadcast through National Parks and on the edges of desert cities.

Desperate, Los Angeles County hires a Department of Ambient Music to save the city from a wave of drought-augmented superfires; equipped with keyboards and effects pedals, wearing trucker hats and plaid, these heroes of the drone wander forth to face the inferno, extinguishing flames with lush carpets of anoxic sound.

(Spotted via New York Magazine).

[Image: Photo by Kim Johnson Flodin/Associated Press, via the

[Image: Photo by Kim Johnson Flodin/Associated Press, via the  [Images: Via the

[Images: Via the