Speaking of cracks in space-time, an urban legend I love is the one about a tomb in Brompton Cemetery, London, allegedly designed by Egyptologist Joseph Bonomi and rumored to be a time machine.

[Image: Via The Clerkenwell Kid].

[Image: Via The Clerkenwell Kid].

A sadly now-defunct blog called The Clerkenwell Kid is a great resource for this. There, we read that Bonomi “traded as an archaeological artist but is thought to have been a tomb raider”:

He is also generally considered to have been the designer of the Egyptian styled “Courtoy” tomb in Brompton cemetery which was ostensibly intended to be the final resting place of “three spinsters”. An interesting legend has grown up around this mausoleum because it is the only one in the cemetery for which there is no record of construction. This, together with Bonomi’s obsession with the afterlife (reflected in the hieroglyphs on the tomb), have been held by some to be evidence that it is not a tomb at all but a time machine and that the three spinsters, if they existed at all, were in fact his time travelling sponsors.

The correct question to ask here is not: is this true? Is this tomb really a time machine? The correct question to ask here is: how freaking cool is this?

The Clerkenwell Kid then goes one better, however, claiming that this urban legend is wrong—because it isn’t ambitious enough.

In fact, we’re told, the tomb was actually one of five such chambers, designed and constructed by Bonomi in an occult conspiracy with his colleague, Samuel Alfred Warner.

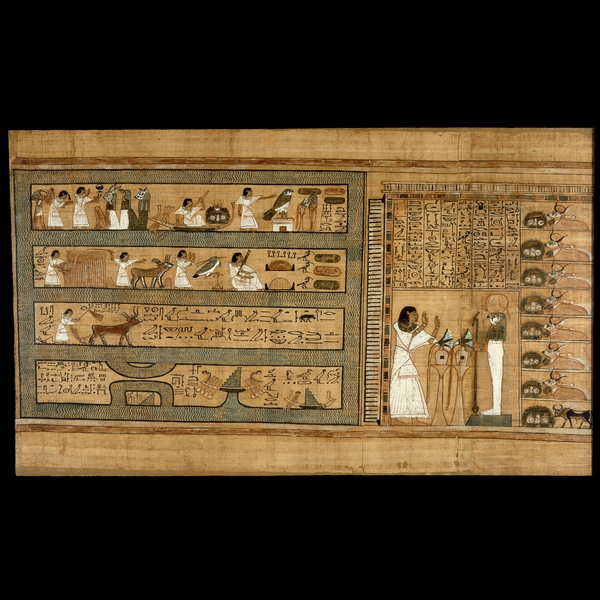

[Image: An otherwise unrelated photo of the Egyptian Book of the Dead, courtesy of the British Museum].

[Image: An otherwise unrelated photo of the Egyptian Book of the Dead, courtesy of the British Museum].

“Amongst several other inventions,” the Kid tells us, “Warner claimed to have developed a mysterious missile capable of destroying ships from a distance”:

The Royal Navy were convinced enough by his demonstrations to pay him to develop this new weaponry but proved unable to reproduce his results independently. This was because what Warner had allegedly discovered (with the help of ancient knowledge gained by Bonomi in Egypt) was an occult way of “teleporting” a bomb a short distance—I suppose you could call it a “psychic torpedo.”

Again, the interest for me here is not whether or not people actually were teleporting themselves—let alone submarine torpedoes!—back and forth through time using Egyptological monuments hidden in London cemeteries.

The interest for me, instead, is at least two-fold: one, how awesome a story this is, and how much I want to tell everyone about it, and, two, how urban infrastructure always seems to inspire, catalyze, or emblematically come to represent these sorts of unexpected narrative investments.

We could say it’s the paranoia of infrastructure: the belief that there is always a bigger story we don’t know, or that someone deliberately isn’t telling us, about how our cities came to be the way they are today. We see this in everything from the water-theft politics of Chinatown to the high-speed rail conspiracies of True Detective Season 2, to this teleportation chamber disguised in plain sight in Brompton Cemetery.

The fact that this story has an atmosphere of the occult only makes literal the notion that the real histories of our cities, the true tales of backstage deals, hidden interests, and untold corruption that made them what they are, have been purposefully obscured from us—they have been occulted—by mysterious figures who prefer we don’t know.

It’s as if narrative paranoia is the default note of infrastructural investigation.

[Image: An otherwise unrelated photo of a “Stela fragment of Horiaa,” courtesy of the British Museum].

[Image: An otherwise unrelated photo of a “Stela fragment of Horiaa,” courtesy of the British Museum].

In any case, The Clerkenwell Kid keeps upping the ante. Remember those five teleportation chambers? Well, there were actually seven!

In dark collaboration, this legend goes, Bonomi and Warner set about constructing “a transportation grid around London” that would “reduce the time taken to travel the large distances of the vast, congested metropolis. To this end they built seven Egyptian teleportation chambers in the most suitable places they could find—in each of the seven new cemeteries that had been built in the capital from 1839.”

The Kid has a great phrase for this, referring to it as “the London funerary teleportation grid.” Surrounding the city like a seven-pointed star, these tombs formed a kind of mortuarial diagram—an urban-scale morbid force-field—that could zap people back and forth through Greenwich space-time.

It’s worth pointing out, however, that the rumors continue, leaking beyond the borders of Old Blighty, to suggest that there is yet another such transportation monument—but it’s over the English Channel, in Paris.

Even within the complicated mythology of these urban legends, this Parisian tomb is an outlier, but it brings with it an interesting plot development. That is, under the cover of developing something like a primitive military radar system that could protect the English Channel from foreign invasion, occult architects and Egyptologists were actually bilking the defense establishment to amass funds and construct this teleportation grid, scattered throughout the war-shadowed cemeteries of western Europe.

[Image: An otherwise unrelated photo of the “Coffin of Tpaeus,” courtesy of the British Museum].

[Image: An otherwise unrelated photo of the “Coffin of Tpaeus,” courtesy of the British Museum].

Now all we need to do is uncover an undocumented Egyptian tomb somewhere in a rainy Swiss mountain churchyard or in the fog-shrouded hills outside Turin, perhaps designed by a bastard child of Bonomi, and we can help keep this urban legend alive…

Until then, for more information check out these three posts over at The Clerkenwell Kid.