Emilio Grifalconi, a character in Georges Perec’s 1978 novel Life: A User’s Manual, at one point discovers “the remains of a table. Its oval top, wonderfully inlaid with mother-of-pearl, was exceptionally well preserved; but its base, a massive, spindle-shaped column of grained wood, turned out to be completely worm-eaten. The worms had done their work in covert, subterranean fashion, creating innumerable ducts and microscopic channels now filled with pulverized wood. No sign of this insidious labor showed on the surface.”

Grifalconi soon realizes that “the only way of preserving the original base – hollowed out as it was, it could no longer suport the weight of the top – was to reinforce it from within; so once he had completely emptied the canals of the their wood dust by suction, he set about injecting them with an almost liquid mixture of lead, alum and asbestos fiber. The operation was successful; but it quickly became apparent that, even thus strengthened, the base was too weak” – and the table would have to be discarded.

In preparing to get rid of the table, however, Grifalconi stumbles upon the idea of “dissolving what was left of the original wood” that still formed the table’s base. This would “disclose the fabulous arborescence within, this exact record of the worms’ life inside the wooden mass: a static, mineral accumulation of all the movements that had constituted their blind existence, their undeviating single-mindedness, their obstinate itineraries; the faithful materialization of all they had eaten and digested as they forced from their dense surroundings the invisible elements needed for their survival, the explicit, visible, immeasurably disturbing image of the endless progressions that had reduced the hardest of woods to an impalpable network of crumbling galleries.”

And if we could sculpt and harden our own paths through cities – across continents – what wormholes of structure and space might we find?

(Earlier on BLDGBLOG: Wormholes).

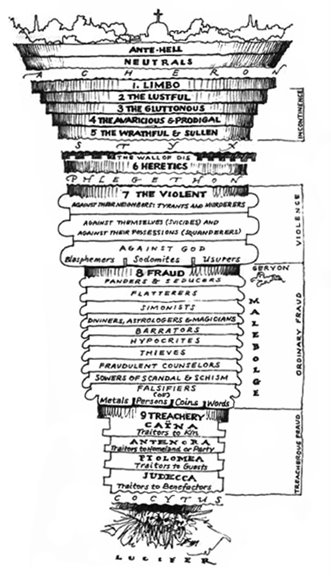

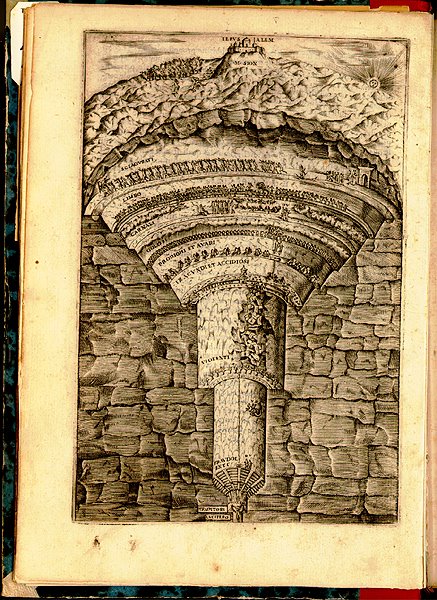

[Image: Dante’s Inferno, as imagined by

[Image: Dante’s Inferno, as imagined by

—complete with interesting subsurface faults and fractured bedrock, in section. One could easily imagine an obscure branch of the Renaissance academy in Rome publishing tract after tract on the exact geotechnical nature of the Inferno. Is it made of granite? Is it kiln-like? Is it slate? Is it ringed by rivers of

—complete with interesting subsurface faults and fractured bedrock, in section. One could easily imagine an obscure branch of the Renaissance academy in Rome publishing tract after tract on the exact geotechnical nature of the Inferno. Is it made of granite? Is it kiln-like? Is it slate? Is it ringed by rivers of  And, finally, making no attempt at all to sustain the visual thread, there’s William Blake–

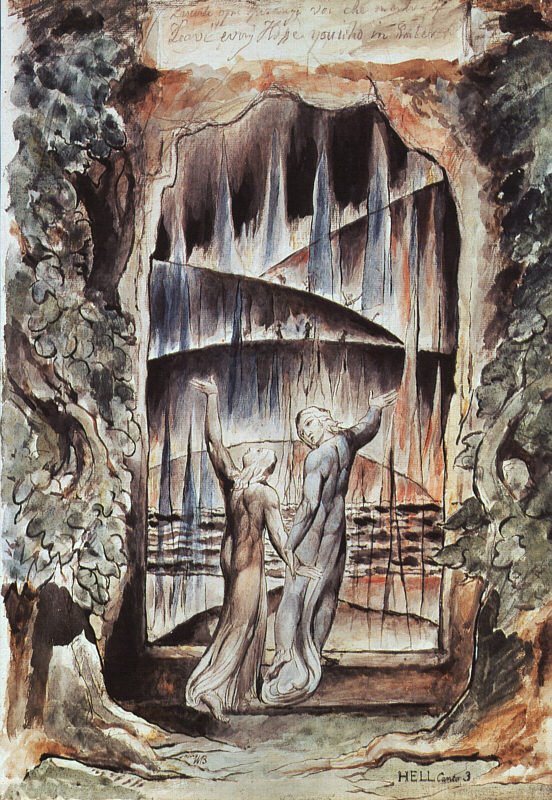

And, finally, making no attempt at all to sustain the visual thread, there’s William Blake– —a perennial favorite of mine, which shows us Dante and Virgil both, walking hand-in-hand through a shimmering geomagnetic curtain, a

—a perennial favorite of mine, which shows us Dante and Virgil both, walking hand-in-hand through a shimmering geomagnetic curtain, a