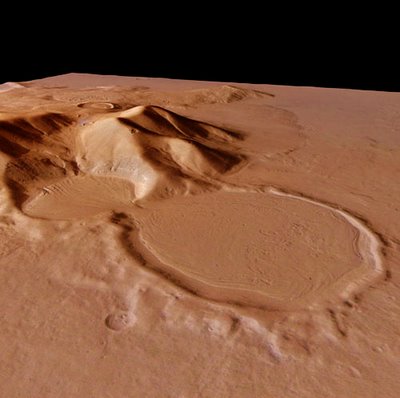

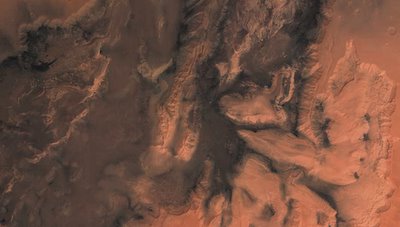

[Image: Tativille; a scene from Playtime. As Jacques Tati later explained, “there were no stars in the film, or rather, the set was the star, at least at the beginning of the film. So I opted for the buildings, facades that were modern but of high quality because it’s not my business to criticise modern architecture” – it was only his job to film it].

[Image: Tativille; a scene from Playtime. As Jacques Tati later explained, “there were no stars in the film, or rather, the set was the star, at least at the beginning of the film. So I opted for the buildings, facades that were modern but of high quality because it’s not my business to criticise modern architecture” – it was only his job to film it].

The idea that an abandoned film set could be archaeologically mistaken for a real city, ten, twenty, even a thousand years in the future, has popped up on BLDGLBOG before.

However, it turns out that there’s an equally interesting story to be found in Tativille, the instant city and film set built for Jacques Tati‘s now legendary Playtime. “Tativille came into existence,” we read in this PDF, “on the ‘Ile de France’ on a huge stretch of waste ground [in Paris]”:

Conceived by Jacques Tati and designed by Eugene Roman, it was strictly a cinema town, born of the needs of the film: big blocks of dwellings, buildings of steel and glass, offices, tarmacked roads, carpark, airport and escalators. About 100 workers laboured ceaselessly for 5 months to construct this revolutionary studio with transparent partitions, which extended over 15,000 square metres. Each building was centrally heated by oil. Two electricity generators guaranteed the maintenance of artificial light on a permanent basis.

During pre-production, “Tati visited many factories and airports throughout Europe before his cinematographer Jean Badal came to the conclusion that he needed to build his own skyscraper. Which is exactly what he did.”

In fact, he built Tativille: an entire city inhabited by no one but actors – who left after each day of filming.

One estimate puts the total mass of built space and material at “11,700 square feet of glass, 38,700 square feet of plastic, 31,500 square feet of timber, and 486,000 square feet of concrete. Tativille had its own power plant and approach road, and building number one had its own working escalator.”

Those hoping to visit the set’s cinematically Romantic remains are out of luck: “I would like to have seen it retained – for the sake of young filmmakers,” Tati claimed, “but it was razed to the ground. Not a brick remains.”

[Image: Tativille; from Playtime].

[Image: Tativille; from Playtime].

Notes for future screenwriters (who credit BLDGBLOG): in the summer of 2009 a delightful Ph.D. candidate from Columbia University, studying architectural history and writing her thesis on the lost sets of mid-20th century French cinema, will fly to Paris for three months. There, she rents a flat near the Seine, sketches buildings in blue ink on cafe napkins, reads Manfredo Tafuri, then sets up her most important interviews – but all is not well. She has strange dreams at night; she thinks she’s being followed; she has a mysterious run-in at the Musée D’Orsay; and she begins to suspect, upon deeper research, that Tativille wasn’t destroyed after all… Till, one day, in a beautifully shot scene at the French National Library – all weird angles and reflective glass walls – our heroine discovers that a small note has been slipped into her jacket pocket.

The note is actually a map, however, with directions addressed solely to her.

For, outside the city, in an arson-plagued banlieue, an old cluster of import warehouses silently waits.

She takes the train – and a small pocket-knife.

Then, standing alone inside one of those warehouses, torch in hand, she finds –

(Thanks, Nicky, for the tip! Of earlier interest: City of the Pharaoh).