[Image: Via Pruned].

[Image: Via Pruned].

In 2002, Alex Pang of the Institute for the Future published a book called Empire and the Sun: Victorian Solar Eclipse Expeditions.

In the Victorian era, Pang explains, “British astronomers carried telescopes and spectroscopes to remote areas of India, the Great Plains of North America, and islands in the Caribbean and Pacific to watch the sun eclipsed by the moon.” These journeys are referred to as “eclipse fieldwork.”

[Image: Stellar depression, or a total eclipse of the sun; from an astrophotography site].

[Image: Stellar depression, or a total eclipse of the sun; from an astrophotography site].

Victorian eclipse expeditions established “eclipse camps,” or instant cities geographically calculated to lie exactly on the forthcoming path of totality. This was, we might say, urban planning as a function of astronomy; or, solar cycles dictating city form.

Observations here could be made of the temporarily extinguished sun, a black star shining over regions so remote they were often entirely unpopulated. On the other hand, Pang writes, locations close to railways were always preferred, as “a small town, easily accessible by railroad, with clear observing conditions and no clouds or dust,” could forestall the inconvenience of camping in the middle of nowhere.

“The first step,” of course, “was to find out the path of totality. By the nineteenth century, the mathematics required to divine the location of the ‘shadow path’ was well developed, and predictions to within a few hundred yards were possible, an excellent level of accuracy since the shadow path itself was more than a hundred miles wide.”

It was here, within this slim zone of moving darkness, spheres of heaven casting shadows on the earth, that an eclipse camp could be established.

[Image: A solar eclipse as seen from space; photographed by Mir].

[Image: A solar eclipse as seen from space; photographed by Mir].

Battling cobras, tigers, cholera, and sunstroke—”less fortunate parties” even faced “epidemics” and “small wars,” perhaps suggesting Indiana Jones and the City of Eclipses—these expeditionary eclipse observers soon established a “standard form” for the camps.

Call it eclipse urbanism: cities built specifically to see, and photograph, the absence of solar light, producing highly accurate films of darkness.:

Every camp had shelter for instruments and baggage, and a darkroom for developing photographic plates. Observers setting up in monasteries [like monks contemplating a black sun, or the eclipse as solar adversary], villas, or estate gardens simply occupied existing buildings, while in unsettled areas, tents or huts were erected, and brick foundations and pedestals built. Eclipse stations were also easily identified by the temporary observatories that parties built. These buildings were usually rectangular, and built of wood on a brick or stone foundation; they housed the larger and more valuable telescopes, spectroscopic cameras, and darkroom, and appeared everywhere between Iowa City and Africa.

The architecture itself was hyper-specialized, designed to assist in recording the Apollonian withdrawal of the total eclipse: “The sensitivity and precision of astrophysical instruments created a demand for spaces that protected them from temperature variations, damp, vibration, and other distractions,” Pang writes. “Consequently, heating systems were designed to stabilize ambient temperatures and minimize temperature gradients from one room to another, or between rooms and stairwells or closets. As telescopes became larger, vibrations from street traffic or motors became intolerable. Engineers responded by designing massive, vibration-free piers, often made of granite or stone, resting on foundations independent of the floors and other parts of the observatory.”

Even “guards were posted” at the peripheries of these specially marked eclipse camps “to keep the curious from playing with instruments, disturbing the astronomers, or even carrying away mementos.” Further, decorative individuation was practiced at each camp: “Bunting or flags were sometimes placed over a camp’s entrance to emphasize its separate identity.”

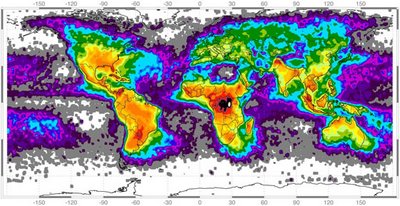

[Image: A map of solar eclipses projected, amazingly, for 2981AD-3000AD; many, many more maps at NASA’s World Atlas of Solar Eclipse Paths].

[Image: A map of solar eclipses projected, amazingly, for 2981AD-3000AD; many, many more maps at NASA’s World Atlas of Solar Eclipse Paths].

As Mircea Eliade writes in The Sacred & The Profane—a survey of spatial practices in “religious myth, symbolism, and ritual”—”some parts of space are qualitatively different from others,” and therefore need to be differentiated. Eliade calls these “sanctuaries that are ‘doors of the gods’ and hence places of passage between heaven and earth.” Eliade—whose textual approach to world religions is outdated and translation-dependent but nonetheless totally fascinating—describes how re-organizing space for purposes that exceed the mundane, even becoming supernatural, should be considered a “cosmicization of unknown territories.” This means the “establishment in a particular place” of a new form of human inhabitation, with a new purpose, holy or even astronomical in nature, thus re-establishing something called the “cosmic pillar.” Eventually that place will be considered “the center of the world.”

Etc. etc.

[Image: A solar eclipse, from this MIT photo collection].

[Image: A solar eclipse, from this MIT photo collection].

In any case, at least two quick things interest me throughout all of this: 1) Are there any examples of eclipse camps that, once the eclipse was over and gone, did not disband, becoming, over time, fully functioning towns or cities? What marks, if any, did that astronomical origin leave in the urban fabric? 2) Given loads of money and a huge amount of land, could you build a railroad that extends for hundreds of miles down the center of a future eclipse path – even an eclipse that isn’t due for decades, or perhaps hundreds of years? You ride from LA to Chicago, or Istanbul to Munich, Beijing to Bangkok, unaware that the skies will turn black along that very route, the train windows will darken, your passage across the earth will enact a moment of astronomy? It’s a pilgrimage route for manic depressives, industrially sprawled across the planet.

[Image: From the BBC. What unearthly flowers would grow by the light of a suicidal sun?].

[Image: From the BBC. What unearthly flowers would grow by the light of a suicidal sun?].

[Image: A solar eclipse as seen from space; photographed by

[Image: A solar eclipse as seen from space; photographed by