[Image: “The Polecat UAV is pictured flying at 15,000 feet by a chaseplane. Polecat’s airframe was ‘laser printed’ rather than machined.” New Scientist Tech].

The same week we found out that jets of the future will be made with plastic, we also read that the U.S. military has been working toward printable airplanes – unmanned drones made by “rapid prototyping.” As New Scientist Tech reports: “In rapid prototyping, a three-dimensional design for a part – a wing strut, say – is fed from a computer-aided design (CAD) system to a microwave-oven-sized chamber dubbed a 3D printer. Inside the chamber, a computer steers two finely focussed, powerful laser beams at a polymer or metal powder, sintering it and fusing it layer by layer to form complex, solid 3D shapes.”

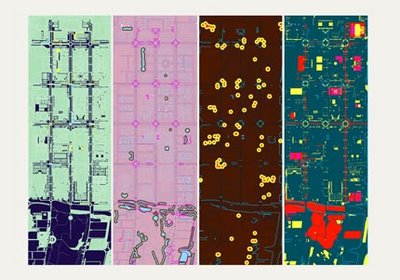

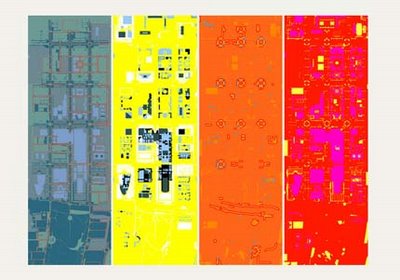

Of course, 3D printing is nothing new; several months ago, for instance, just about everyone in the universe learned that 3D buildings and cityscapes can be printed using images from Google Earth.

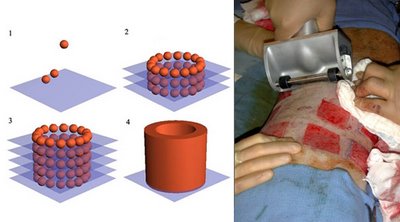

Even more strangely, you can also print fully-functioning body parts using “droplets of ‘bioink’,” which are “clumps of cells a few hundred micrometres in diameter.” In other words, if you “alternate layers of supporting gel, dubbed ‘biopaper’, with the bioink droplets,” and if you “build tubes that could serve as blood vessels, for instance,” then, through bio-printing, these will become the “successive rings containing muscle and endothelial cells, which line our arteries and veins.”

This Frankenstein-meets-Hewlett-Packard technology can be used to “print any desired structure.” Indeed, there are now “printing heads that extrude clumps of cells mechanically so that they emerge one by one from a micropipette. This results in a higher density of cells in the final printed structure, meaning that an authentic tissue structure can be created faster.” (What about a photocopier?) Finally, skeptics will benefit from learning that “cells seem to survive the printing process well. When layers of chicken heart cells were printed they quickly begin behaving as they would in a real organ. ‘After 19 hours or so, the whole structure starts to beat in a synchronous manner.'” (A bit more on this here).

The Oliver Twist of tomorrow, then, will be a poor boy, printed in obscurity…

So the question naturally arises: what if you were to combine all these? You’d get a vast, self-printing city-organism, whose skies are criss-crossed with machine-birds of prey; when buildings reach the age of senility, forgetting how many floors they contain, they are melted down into rivers of ink and pooled in living reservoirs to be printed once again; molds and fungi and architectural infections bloom, growing atop one another till new parasite structures form, small Gothic rooms in which the homeless live.

All of which reminds me, somewhat disjunctively, of the following rather unoriginal statement: the default condition of all literary genres will soon be science-fiction. You simply will not be able to write about the world without incorporating these weird new technologies.

Science-fiction and social realism will become one and the same thing.

Look at the recent genre-defying work of Kazuo Ishiguro, Michel Houellebecq, David Mitchell, Rupert Thomson, Alex Garland; soon even Ian McEwan will be writing sci-fi. Note, as well, that whilst mainstream American literary novelists appear increasingly incapable of doing anything other than reimagining their own national past – Philip Roth, say, or the forthcoming Thomas Pynchon – as if endlessly recycling historical micro-narratives will result in something new – Anglo-European fiction appears to have accepted, with great success and enthusiasm, the futurist inclinations already so obvious in everyday life.

To be rather broad here – for instance, does Michael Cunningham invalidate my argument? do I even have an argument? – it seems that while British fiction in particular has already accounted for the slippage of contemporary life into sci-fi, even welcoming this phenomenon with a newfound literary ambition, mainstream American fiction is content simply to enroll itself in unnecessary MFA programs, writing 800-page novels about family farms, the period between WWI and II, shopping, or the supposedly “atmospheric” end of the 19th century.

Run-of-the-mill student architectural proposals are already more stimulating than most of today’s American novels. Architectural proposals have ideas.

Meanwhile, the rest of the world has already discovered the future, and it’s no real wonder that the U.S. publishing industry is in the midst of a kind of slow financial crisis. In fact, you only have to look at the ongoing revival of interest in Philip K. Dick – sci-fi novelist and volunteer FBI informant – to see that Americans don’t exactly lack a literary taste for the future; it’s just that all the wrong novels keep getting published here.

In any case, there are a million exceptions to this argument; feel free to rip it apart. For example, where does The Da Vinci Code fit in all this? Etc. etc.