[Image: From Sean Regan’s final project at Urban Islands 2009].

[Image: From Sean Regan’s final project at Urban Islands 2009].

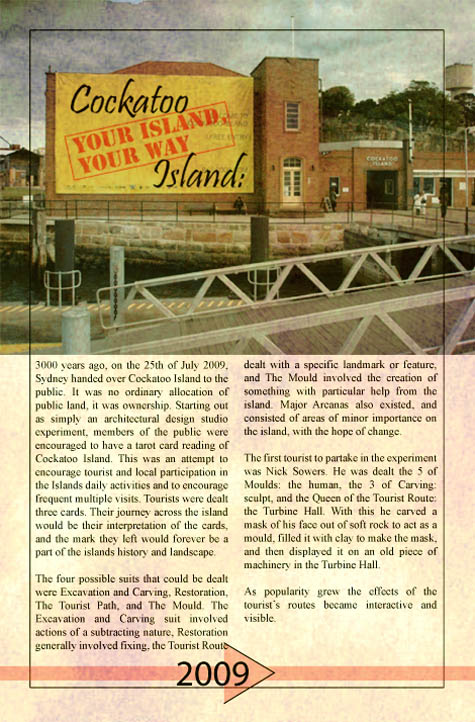

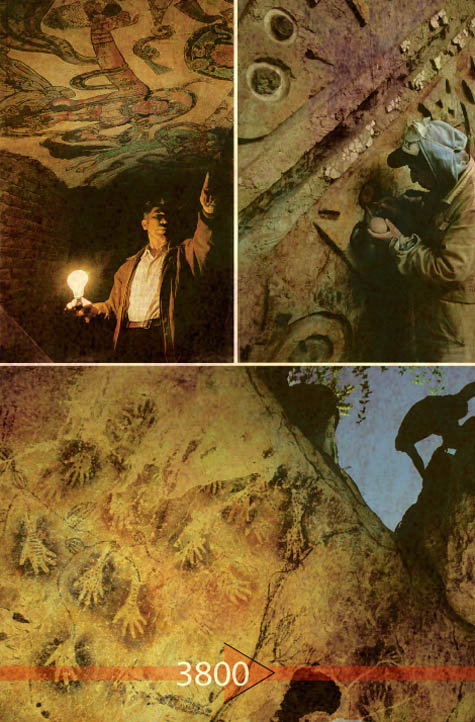

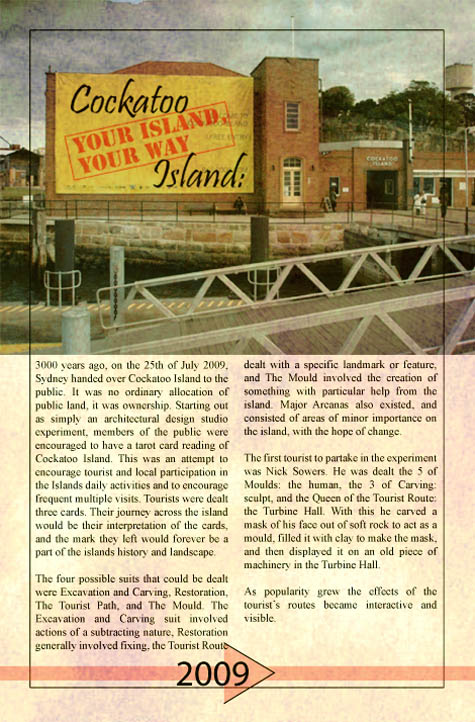

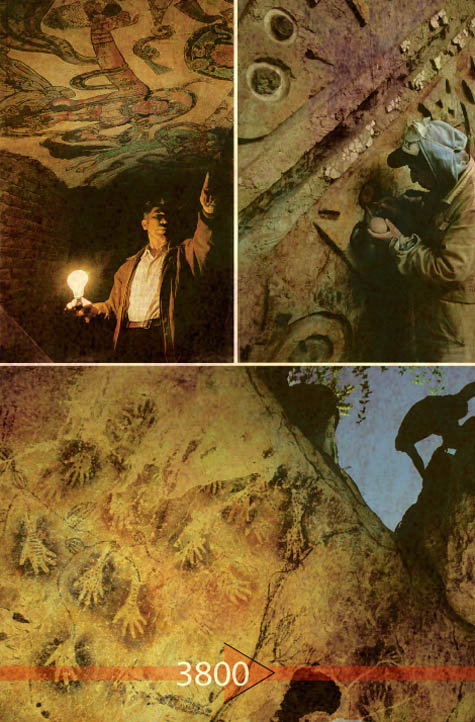

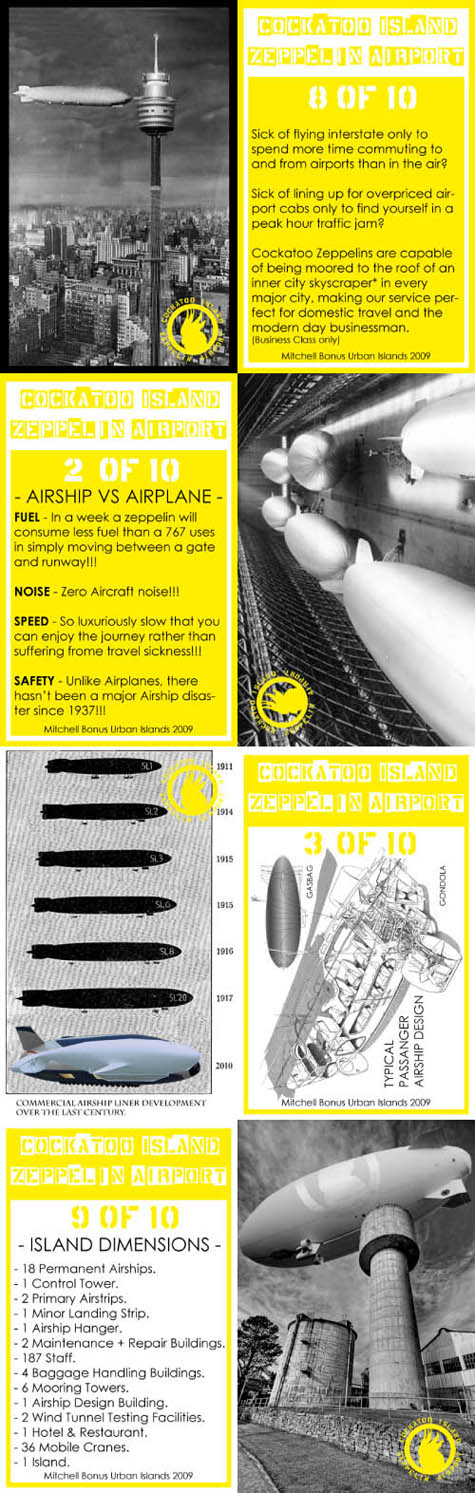

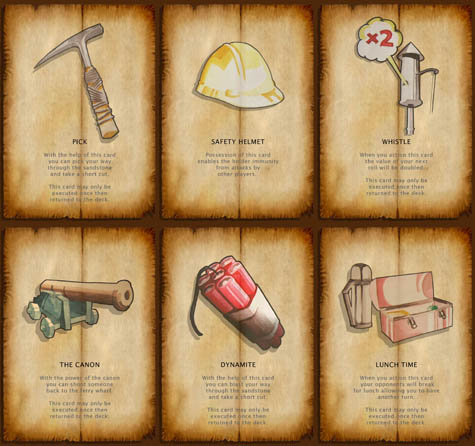

For his final project at Urban Islands – hosted the other week in Sydney and previously discussed here, here, here, here, and elsewhere – Sean Regan produced a heavily-illustrated fake article for a distant-future issue of National Geographic.

[Image: Image and text from Sean Regan’s final project at Urban Islands 2009].

[Image: Image and text from Sean Regan’s final project at Urban Islands 2009].

Piecing together found imagery to create his own narrative exploration of Cockatoo Island, Sean addressed the following question: What would happen to the island if it was no longer historically preserved but deliberately, often violently, altered by the tourists who came to visit it?

[Images: From Sean Regan’s final project at Urban Islands 2009].

[Images: From Sean Regan’s final project at Urban Islands 2009].

That is, what if tourists were given a more or less complete freedom to carve, excavate, blast, construct, drill, tunnel, and alter their way across the island landscape?

[Images: From Sean Regan’s final project at Urban Islands 2009].

[Images: From Sean Regan’s final project at Urban Islands 2009].

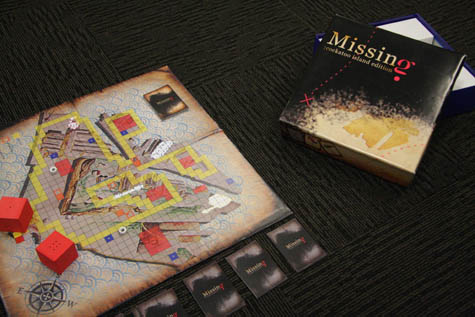

Because of the nature of the studio itself – which was based around the idea of random program generation through the design and distribution of Cockatoo Island-themed “Tarot” cards – this would take the specific form of tourists being handed a series of cards upon arrival at the island.

On these cards would be actions, sites, tools, materials, and so on that the visitors would be free to interpret – acting out their conclusions in physical form through often drastic and completely unregulated interventions into the structure of the island itself.

[Images: From Sean Regan’s final project at Urban Islands 2009].

[Images: From Sean Regan’s final project at Urban Islands 2009].

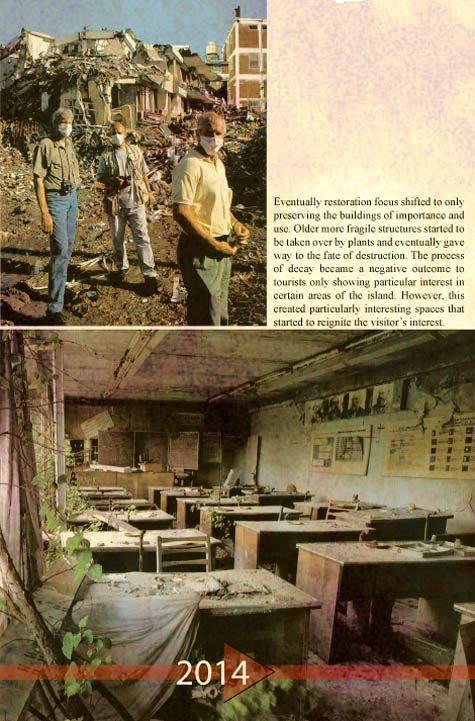

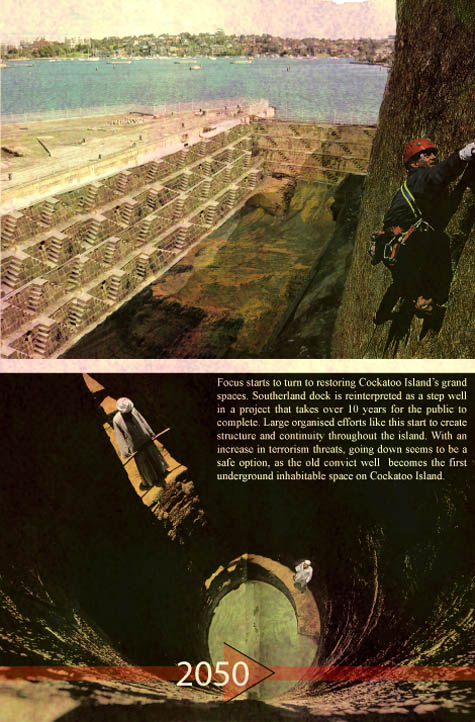

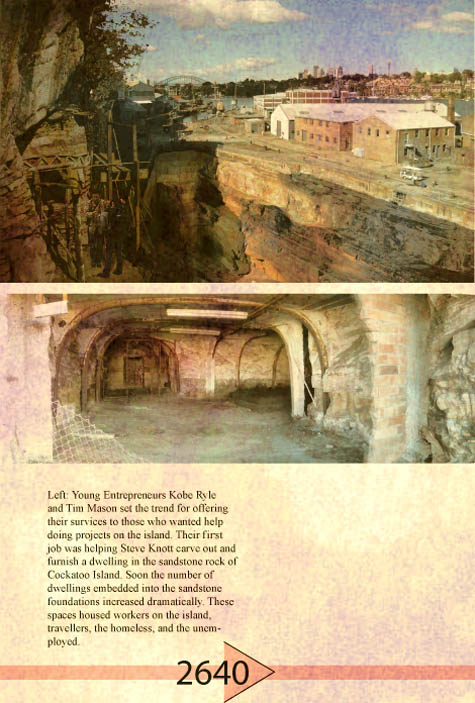

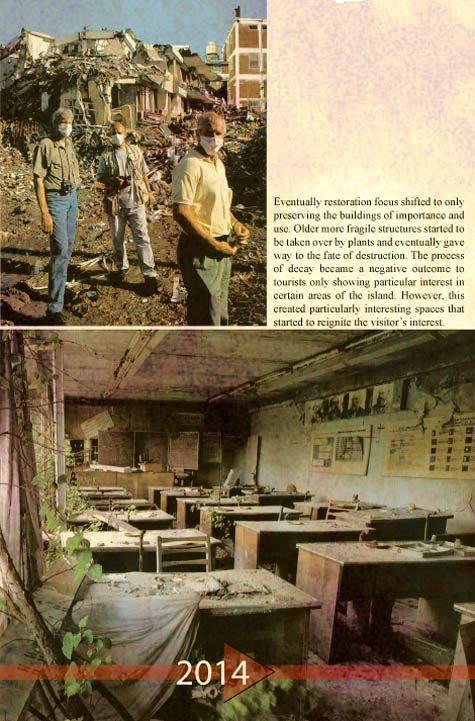

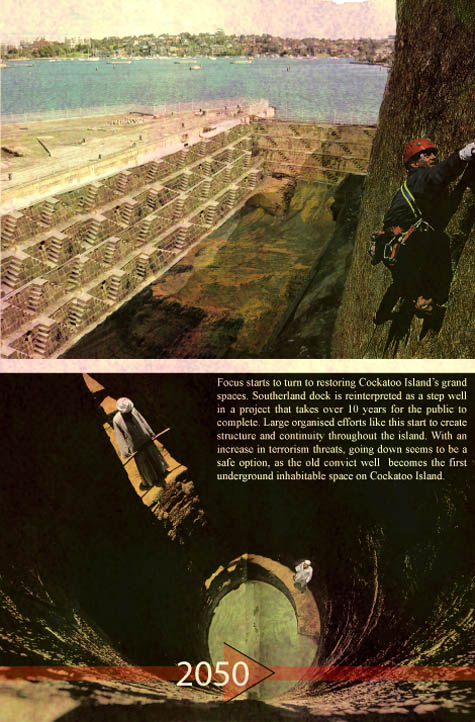

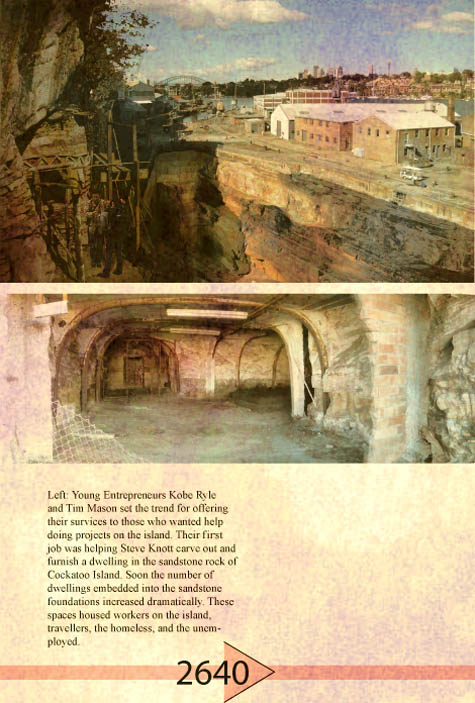

Over thousands of years, then, Cockatoo Island would be transformed through tourist excavations into an increasingly subterranean mazescape of new, improvised passageways – think of it as a kind of geotechnical free jazz, burrowing its way through new forms and structures of geology.

The walls themselves become gradually covered in post-aboriginal myths and cave paintings, and anthropologists from around the world come to Sydney to study the altered massing of Cockatoo.

It was pointed out in the final studio crit, as exhaustively documented by fellow participant Nick Sowers over on Archinect, that this sort of anything-goes approach to managing Cockatoo Island’s future is diametrically opposed to the strange and disappointing historical stasis in which the island is currently trapped.

The island needn’t be frozen in place, in other words, becoming a museum of its last role (an industrial shipbuilding yard); it could, in fact, be endlessly transformed, over decades, centuries, and even thousands of years, to become a palimpsestic reduction of eras, needs, and fleeting intentions.

After all, it was pointed out, that’s exactly what Cockatoo is already: a delirium of excavations. It is sliced through with tunnels. Its cliffsides are artificial. Its shorelines have been expanded. Its native species have been replaced.

But it’s as if Cockatoo’s preservationists have been saying, “We will celebrate this island… by transforming it into the very thing it is has never been: static.”

In this context, perhaps Sean’s project isn’t merely a speculative fantasy of permanent excavation – proposing a future state of geological amnesia in which constant, superficial erasure reacts mindlessly to the past – but a necessary demonstration of how historic preservation often fails to reveal the very essence of the sites it seeks to celebrate.

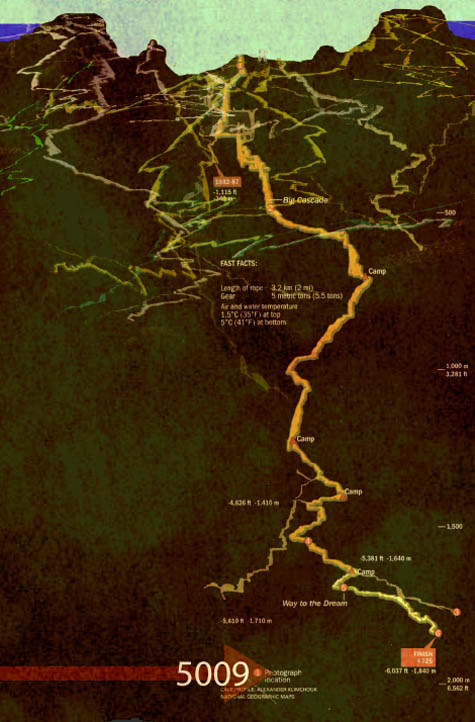

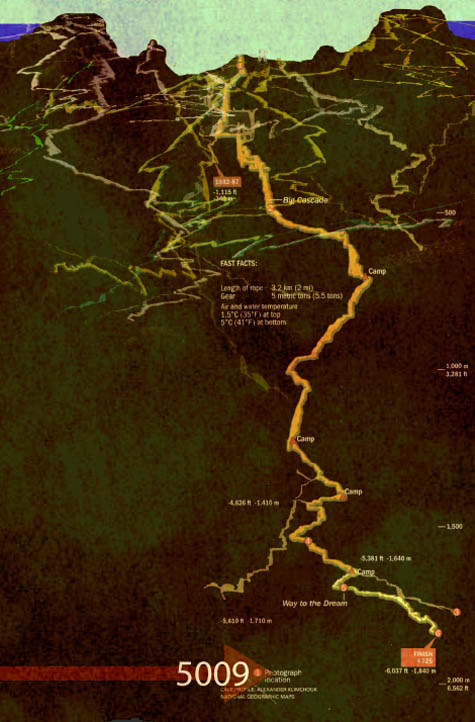

[Image: Cockatoo Island is now a warren of artificial caves extending for kilometers into the earth’s surface below. From Sean Regan’s final project at Urban Islands 2009].

[Image: Cockatoo Island is now a warren of artificial caves extending for kilometers into the earth’s surface below. From Sean Regan’s final project at Urban Islands 2009].

In any case, the sandstone plateau of the island, the project suggests, will eventually be scraped away to levels far below the waves of Sydney Harbor, requiring the construction of massive ring dams to hold back the sea. The entire island is thus placed into a state of dry dock.

By the year A.D. 5009, Cockatoo is nothing more than an opening into the underworld, the island’s terrestrial presence having been replaced with the thousands of tunnels now spiraling away into the earth below.

Of course, the images that appear here have been deliberately aged to look as if they were found in an excavation several thousand years from now, but Sean’s collaging skills, disguised beneath those stains and discolorations, are extraordinary. It was a genuine pleasure to watch this project take shape over the second half of our two-week studio.

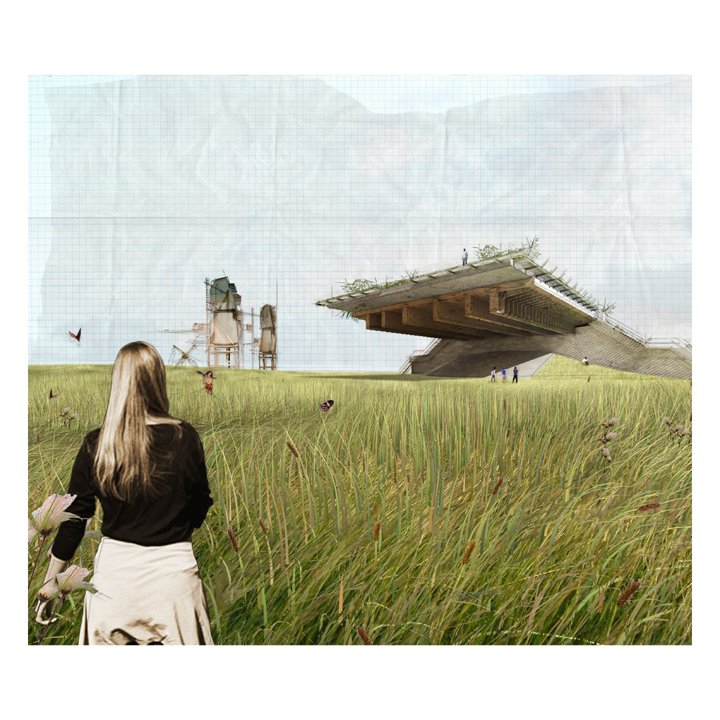

[Image: “The Garden of Machines” by Nathan Freise, from his extraordinarily well-produced Unseen Realities series; perhaps it’s Andrew Wyeth meeting the U.S. interstate highway system in a world art-directed by Guillermo del Toro].

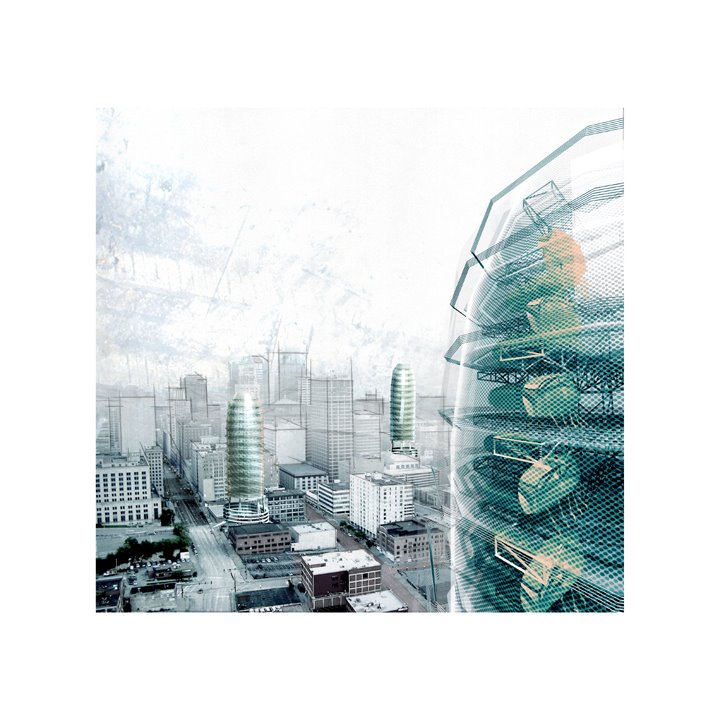

[Image: “The Garden of Machines” by Nathan Freise, from his extraordinarily well-produced Unseen Realities series; perhaps it’s Andrew Wyeth meeting the U.S. interstate highway system in a world art-directed by Guillermo del Toro]. [Image: “The Garden of Machines (Dwell)” by Nathan Freise, from Unseen Realities; this one brings to mind some 22nd-century Charles Darwin watching the machine-birds of tomorrow’s eco-motorways, where billboards become breeding grounds for species we’ve never seen before].

[Image: “The Garden of Machines (Dwell)” by Nathan Freise, from Unseen Realities; this one brings to mind some 22nd-century Charles Darwin watching the machine-birds of tomorrow’s eco-motorways, where billboards become breeding grounds for species we’ve never seen before]. [Image: “Transience (The Nomads)” by Nathan Freise, from Unseen Realities].

[Image: “Transience (The Nomads)” by Nathan Freise, from Unseen Realities].  [Images: “Transience (Decay and Renewal)” by Nathan Freise, from Unseen Realities].

[Images: “Transience (Decay and Renewal)” by Nathan Freise, from Unseen Realities]. [Image: From Sean Regan’s final project at

[Image: From Sean Regan’s final project at  [Image: Image and text from Sean Regan’s final project at

[Image: Image and text from Sean Regan’s final project at

[Images: From Sean Regan’s final project at

[Images: From Sean Regan’s final project at

[Images: From Sean Regan’s final project at

[Images: From Sean Regan’s final project at

[Images: From Sean Regan’s final project at

[Images: From Sean Regan’s final project at  [Image: Cockatoo Island is now a warren of artificial caves extending for kilometers into the earth’s surface below. From Sean Regan’s final project at

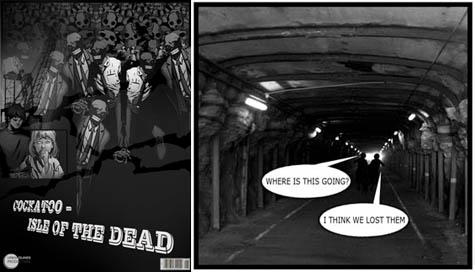

[Image: Cockatoo Island is now a warren of artificial caves extending for kilometers into the earth’s surface below. From Sean Regan’s final project at  [Image: Scanned & collaged comic book images appear alongside a photo from the

[Image: Scanned & collaged comic book images appear alongside a photo from the  [Image: From Cockatoo: Isle of the Dead by Yael Kaufman, produced for

[Image: From Cockatoo: Isle of the Dead by Yael Kaufman, produced for  [Image: More collaged comic book images and photos from Cockatoo Island by Yael Kaufman].

[Image: More collaged comic book images and photos from Cockatoo Island by Yael Kaufman]. [Image: From Cockatoo: Isle of the Dead by Yael Kaufman, produced for

[Image: From Cockatoo: Isle of the Dead by Yael Kaufman, produced for

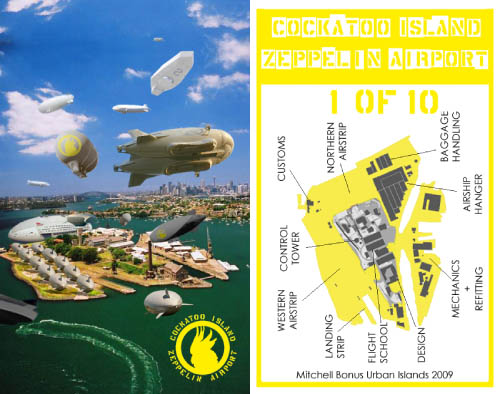

[Image: The front and back of an architectural trading card, designed by Mitchell Bonus for

[Image: The front and back of an architectural trading card, designed by Mitchell Bonus for  [Image: The fronts and backs of four architectural trading cards, designed by Mitchell Bonus].

[Image: The fronts and backs of four architectural trading cards, designed by Mitchell Bonus]. [Image: Four more architectural futures cards, designed by Mitchell Bonus].

[Image: Four more architectural futures cards, designed by Mitchell Bonus]. [Image: The front and back of one card by Mitchell Bonus, from

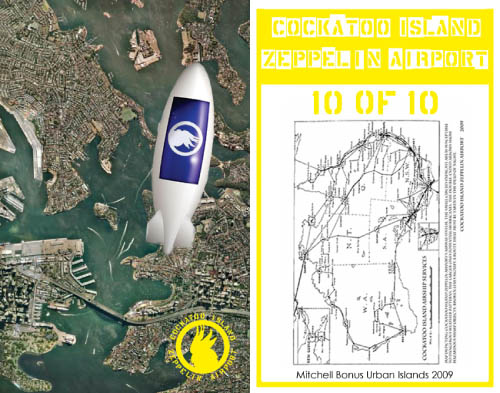

[Image: The front and back of one card by Mitchell Bonus, from  [Image: Playing Tristan Davison’s Missing: Cockatoo Island Edition].

[Image: Playing Tristan Davison’s Missing: Cockatoo Island Edition]. [Image: Missing: Cockatoo Island Edition by Tristan Davison].

[Image: Missing: Cockatoo Island Edition by Tristan Davison]. [Images: Building Cards from Tristan Davison’s Missing: Cockatoo Island Edition, produced in less than one week].

[Images: Building Cards from Tristan Davison’s Missing: Cockatoo Island Edition, produced in less than one week]. [Images: Action Cards from Missing: Cockatoo Island Edition].

[Images: Action Cards from Missing: Cockatoo Island Edition]. [Images: The board of Tristan Davison’s Missing: Cockatoo Island Edition].

[Images: The board of Tristan Davison’s Missing: Cockatoo Island Edition]. [Image: The

[Image: The  [Image: “

[Image: “ [Image: The Pantheon, photographed by

[Image: The Pantheon, photographed by  [Image: A human blink, via

[Image: A human blink, via  [Image: The dimensions of an island: a sign posted on

[Image: The dimensions of an island: a sign posted on  [Image: The gridded rails of a lost interior,

[Image: The gridded rails of a lost interior,  [Image:

[Image:  [Image: Sydney’s

[Image: Sydney’s  [Image: This season’s lecture schedule at Sydney’s Tusculum;

[Image: This season’s lecture schedule at Sydney’s Tusculum;