[Images: Photos via the BBC and the Washington Post].

[Images: Photos via the BBC and the Washington Post].

A story on the BBC that I neglected to blog last week explains how the capital of Chad will soon be encircled by a gigantic trench: “A three-metre [10-foot] deep trench is being dug around Chad’s capital, N’Djamena, to force vehicles through one of a few fortified gateways into the dusty city,” we read.

Additionally, like some strange, new, paranoid version of Easter Island, “tree surgeons [have] cut down centuries-old trees that lined the city’s main avenue for fear they could provide cover for attackers.”

Prepared for war and insurgency, then, the city will strip itself bare.

“It’s part of our strategy,” the Interior Minister claims. These are just “initiatives to prevent attacks from rebels based in the east of the country.”

It’s also interesting to note, though, that, in the absence of enemy air power, basic urban design moves – like trenches and gates – can still be used as an effective tactic of defense during war.

[Image: The “trenches of approach,” via Wikipedia; view larger].

[Image: The “trenches of approach,” via Wikipedia; view larger].

In fact, I’m reminded of Alberto Pérez-Gómez’s book, Architecture and the Crisis of Modern Science, in which he writes about the geometric history of urban fortifications – such as those seen on Deputy Dog last month.

As Pérez-Gómez writes, referring to military treatises produced in western Europe in the 16th and 17th centuries: “All military problems were described in terms of lines and angles…”

War, to put it glibly, was a function of measurement and trigonometry.

Bernard Palissy, in particular, a 17th century theoretician and builder of fortified space, discovered that some of the best military geometries were to be found in the bodies of maritime organisms:

Palissy believed that existing fortified towns failed because their protecting walls were not really part of the towns’ architecture. He tried to find better ideas in the treatises of the old masters, but was sadly disappointed. In desperation, he turned to nature and after traversing woods, mountains, and valleys, he arrived at the sea. It was there that he observed “the miraculous protection of mollusks like oysters and snails.”

As Pérez-Gómez summarizes this: “The sea snail was clearly the best prototype for a fortified city.”

What’s particularly interesting about this, however, is that Palissy – and other military architects of the time – saw fortified cities as all but divinely ordained; quoting an architect named Jacques Perret de Chambéry, Pérez-Gómez notes that military architecture “could thus represent an order in which ‘all nations may praise the Lord’ and ‘live according to His Holy Laws.'”

Military architecture was, to this way of thinking, religious architecture.

[Image: Star fort diagrams, via Wikipedia].

[Image: Star fort diagrams, via Wikipedia].

Things even got a bit Da Vinci Code here. For instance, we read that certain military architects “recommended the use of square, pentagonal, or hexagonal fortifications since these figures were symbols of the relation between the human body and the cosmos.” Further, dividing space within these fortified cities into four distinct parts meant that the space could correspond “to the four regions of the sky, thus emulating the cosmic order.”

In fact, Pérez-Gómez notes, a man named Mathias Dögen even included, in a treatise on war and space, “long sections in which he provided detailed instructions on how to conquer cities, taken from the ‘Laws’ established in the Holy Scriptures.”

This idea – that military architecture was a way to inscribe “cosmic order” onto the surface of the earth – is almost ridiculously interesting. How does that play out today – in Camp Bondsteel, for instance?

But even the briefest suggestion that something as tactical, pragmatic, and strategically rooted in measurement as 17th century European warfare might actually have harbored this mystical underside surely deserves more exploration elsewhere.

[Image: Star fort diagrams, via Wikipedia].

[Image: Star fort diagrams, via Wikipedia].

In any case, reading this in the context of today’s War on Terror – with its slow encroachment of blast walls and other anti-terror architecture into the very heart of our now fortified cities – I’m led to ask if we might be witnessing the makeshift inscription of a new sort of “cosmic order” into urban space, worldwide.

Or, to put it another way: How do well-fortified Western cities in an age of Global Terror give shape to, or represent, much larger, more subtle, and perhaps immaterial details of a religious world view?

Might we yet see a religious theorization of 21st century urban space, in which anti-terror architecture plays a central role?

Is there an underexplored theological dimension to crash barriers, Bremer walls, and armed checkpoints?

That may wildly overstate the case, of course – but I’m reminded of an article in Salon, published way back in 2006, where we read:

To appreciate how America has changed since 9/11, walk slowly through any major city. What you’ll see dotting the landscape is the physical embodiment of fear. Security installations put up after the attacks continue to block public access and wrangle pedestrian traffic. Outside Manhattan’s Port Authority Bus Terminal, garish purple planters menace rush-hour pedestrian traffic. The gigantic planters have abandoned all horticultural ambition, many of them blooming with nothing more than trash and untilled dirt.

Further:

It’s not just the barriers, it’s also the buildings. Since 9/11, risk consultants working for police departments, federal agencies and insurance companies have wrested control over many new construction plans. “There’s a sense that security experts are acting as the associate architects on every project built today,” says Paul Goldberger, the architecture critic of the New Yorker. Consultants tend to encourage architectural bulk at the expense of grace.

So the question is: What happens when we put the security-obsessed 21st century city – whether that’s N’Djamena, Chad, with its 10-foot deep trench or New York City with its flowerless planters – into the context of Alberto Pérez-Gómez’s book on the religious significance of military fortifications? How does that change the discussion?

[Image: A photo by Randy of a fortified road on the way to Rachel’s Tomb, Bethlehem – an old city of stone walls overshadowed by a new city of concrete blast walls].

[Image: A photo by Randy of a fortified road on the way to Rachel’s Tomb, Bethlehem – an old city of stone walls overshadowed by a new city of concrete blast walls].

So if religiously inspired military architects of the 17th century were the “risk consultants” and urban “security experts” of their day, then how might their treatises read if updated for the War on Terror?

[Image: Photo courtesy of the U.S. Navy, via the New York Times].

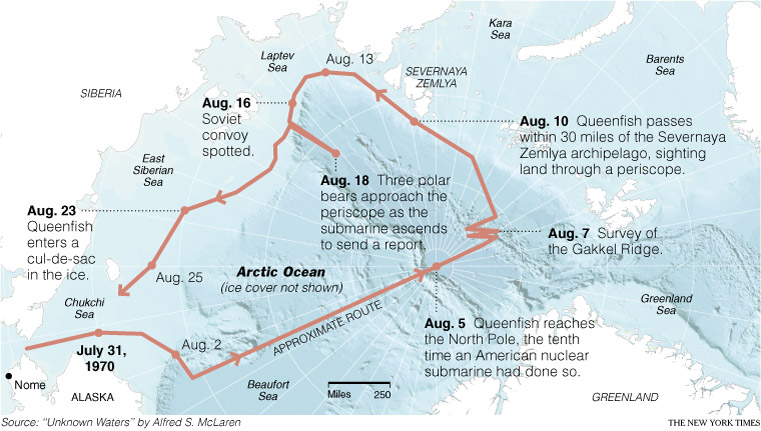

[Image: Photo courtesy of the U.S. Navy, via the New York Times]. [Image: Map courtesy of the New York Times, based on information from Unknown Waters by Alfred S. McLaren].

[Image: Map courtesy of the New York Times, based on information from Unknown Waters by Alfred S. McLaren]. It’s about what the world might look like if Hollywood celebrities, hip-hop moguls, international financiers, and so on got addicted to digging tunnels…

It’s about what the world might look like if Hollywood celebrities, hip-hop moguls, international financiers, and so on got addicted to digging tunnels… [Images: Photos via the

[Images: Photos via the  [Image: The “trenches of approach,” via

[Image: The “trenches of approach,” via  [Image: Star fort diagrams, via

[Image: Star fort diagrams, via  [Image: Star fort diagrams, via

[Image: Star fort diagrams, via  [Image: A photo by

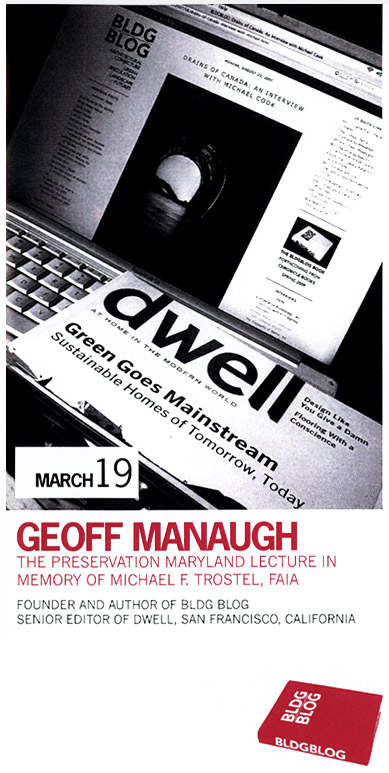

[Image: A photo by  With the BLDGBLOG Book still on my plate here, it might be another slow week on the blog – maybe not – but I do want to announce something else before it’s too late: and that’s that I will be giving an hour-long lecture next week in Baltimore, hosted by the

With the BLDGBLOG Book still on my plate here, it might be another slow week on the blog – maybe not – but I do want to announce something else before it’s too late: and that’s that I will be giving an hour-long lecture next week in Baltimore, hosted by the  Specifically, it’s this year’s Michael F. Trostel Lecture, sponsored by Preservation Maryland.

Specifically, it’s this year’s Michael F. Trostel Lecture, sponsored by Preservation Maryland.

Finally, the AIA-Baltimore webpage says, incorrectly, that I am the founder and editor of

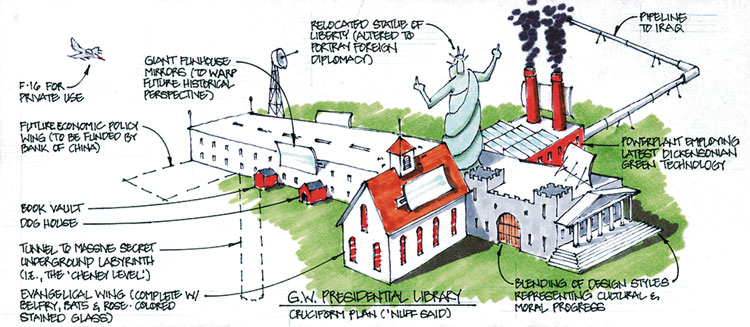

Finally, the AIA-Baltimore webpage says, incorrectly, that I am the founder and editor of  [Image: From the Back-of-the-Envelope Design Contest, sponsored by the

[Image: From the Back-of-the-Envelope Design Contest, sponsored by the

[Images: From the Back-of-the-Envelope Design Contest, sponsored by the

[Images: From the Back-of-the-Envelope Design Contest, sponsored by the  [Image: A

[Image: A  [Image: A

[Image: A  [Image:

[Image:  [Image:

[Image:  [Image: Screen shots from artist

[Image: Screen shots from artist  [Image: Photo by Matt York for the Associated Press (

[Image: Photo by Matt York for the Associated Press ( [Images: The water guns are opened. Photos by Matt York for the Associated Press (

[Images: The water guns are opened. Photos by Matt York for the Associated Press ( [Image: Photo via

[Image: Photo via  [Image: Photo courtesy of American Images, Marshfield, WI, via

[Image: Photo courtesy of American Images, Marshfield, WI, via  [Image: Photo by Dean C. K. Cox for The International Herald Tribune].

[Image: Photo by Dean C. K. Cox for The International Herald Tribune]. [Image: A scene from “

[Image: A scene from “ [Image: A scene from “

[Image: A scene from “ [Image: A scene from “

[Image: A scene from “

[Images: Scenes from “

[Images: Scenes from “

[Images: Scenes from “

[Images: Scenes from “

[Images: Scenes from “

[Images: Scenes from “ [Image: “Abandoned equipment stands in the snow near the top of an underground tunnel that was once used to drain mine water.” Photo by Kevin Moloney for

[Image: “Abandoned equipment stands in the snow near the top of an underground tunnel that was once used to drain mine water.” Photo by Kevin Moloney for