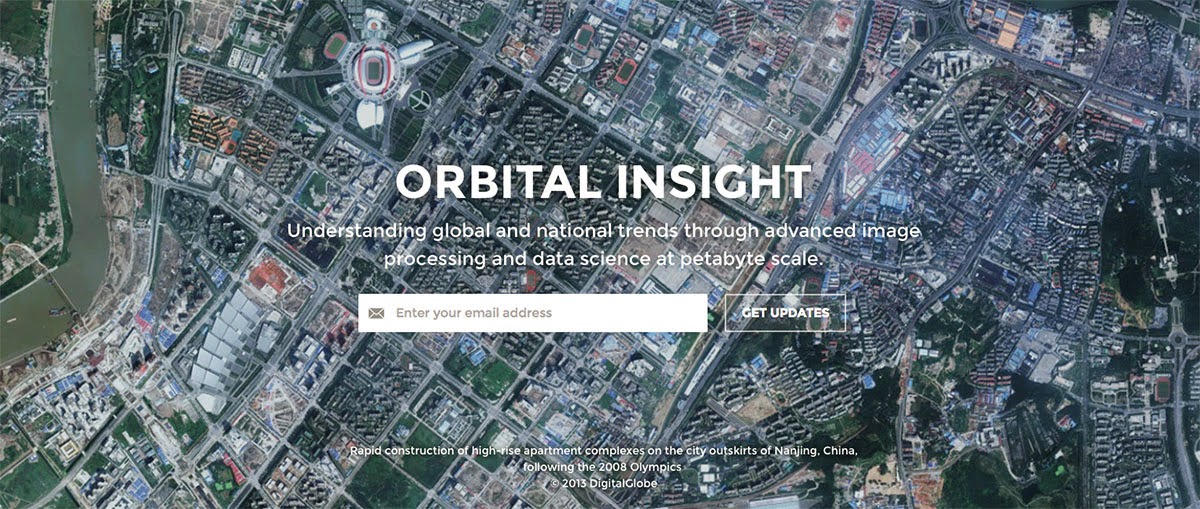

[Image: A screen grab from the homepage of Orbital Insight].

[Image: A screen grab from the homepage of Orbital Insight].

Proving that some market somewhere will find a value for anything, a company called Orbital Insight is now tracking “the shadows cast by half-finished Chinese buildings” as a possible indicator for where the country’s economy might be headed.

As the Wall Street Journal explains, Orbital Insight is part of a new “coterie of entrepreneurs selling analysis of obscure data sets to traders in search of even the smallest edges.” In many cases, these “obscure data sets” are explicitly spatial:

Take the changing shadows of Chinese buildings, which Mr. Crawford [of Orbital Insight] says can provide a glimpse into whether that country’s construction boom is speeding up or slowing down. Mr. Crawford’s company, Orbital Insight Inc., is analyzing satellite images of construction sites in 30 Chinese cities, with the goal of giving traders independent data so they don’t need to rely on government statistics.

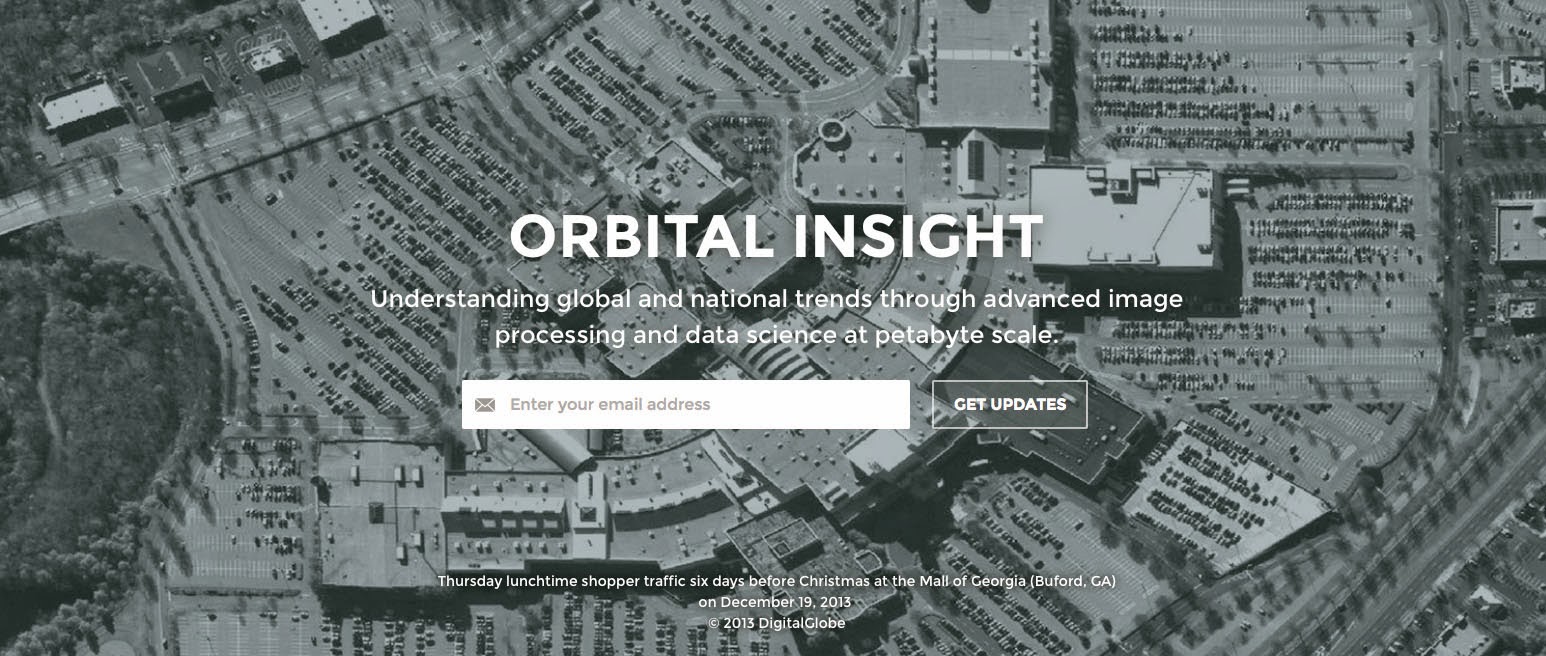

If watching the shadows of Chinese cities from space isn’t quite your cup of tea, then consider that the company “is also selling analysis of satellite imagery of cornfields to predict how crops will shape up and studies of parking lots that could provide an early indicator of retail sales and quarterly earnings of companies such as Wal-Mart Stores Inc. and Home Depot Inc.”

[Image: A screen grab from the homepage of Orbital Insight].

[Image: A screen grab from the homepage of Orbital Insight].

The resulting data might not even prove useful; but, in a great example of what we might call just-in-case informatics, it’s scooped up and packaged anyway.

The notion that there are fortunes to be made given advance notice of even the tiniest spatial details of the world is both astonishing and sadly predictable—that something as intangible as the slowly elongating shadows of construction sites in China could be turned into a proprietary data point, an informational product sold to insatiable investors.

Everything has a price—including the knowledge of how many cars are currently parked outside Home Depot.

Read more at the Wall Street Journal.

This reminds me of the fractured, distributed intelligence community described in Stephenson's Snow Crash: every scrap gets recorded and uploaded in case an analyst might find some value:

"Hiro gets information. It may be gossip, videotape, audiotape, a fragment of a computer disk, a xerox of a document. It can even be a joke based on the latest highly publicized disaster. … Millions of other CIC stringers are uploading millions of other fragments at the same time. CIC’s clients, mostly large corporations and Sovereigns, rifle through the Library looking for useful information, and if they find a use for something that Hiro put into it, Hiro gets paid. … [But] he has been learning the hard way that 99 percent of the information in the Library never gets used at all."

In the early 90s I remember talking to some commodities traders about cocoa futures. Basically, there was no money to be made if you were up against Mars or Hershey. They could afford to buy satellite images and hire aircraft, so they knew how the crop was progressing, and they were the biggest users of the end product. They could out hedge you, and wouldn't leave a dime on the table.

The airlines, on the other hand, had a win-win game with oil futures. Basically, when the futures came due, they'd have two choices, turn it into jet fuel or turn it into heating oil, so they were more into long range forecasting.