[Image: Alexander Graham Bell, inventor of the telephone, steps forth into the ruins of the “extinct city” of Pompeii; courtesy U.S. Library of Congress].

[Image: Alexander Graham Bell, inventor of the telephone, steps forth into the ruins of the “extinct city” of Pompeii; courtesy U.S. Library of Congress].

The ruins of Pompeii are being wired-up by a company otherwise known for its work as a manufacturer of military drones and “electronic warfare equipment,” Phys.org reports. Finmeccanica, the “Italian aerospace and defense giant,” has been contracted to install a high-tech sensor network amongst the barely stabilized walls and streets of this city once buried by a volcanic eruption nearly 2,000 years ago, in the hopes of monitoring unstable ground conditions on the sites.

Slippage and instability threaten to bring some of the buildings down, not just putting the site’s UNESCO-designated mansions at risk but potentially injuring (or worse) its annual hordes of international visitors.

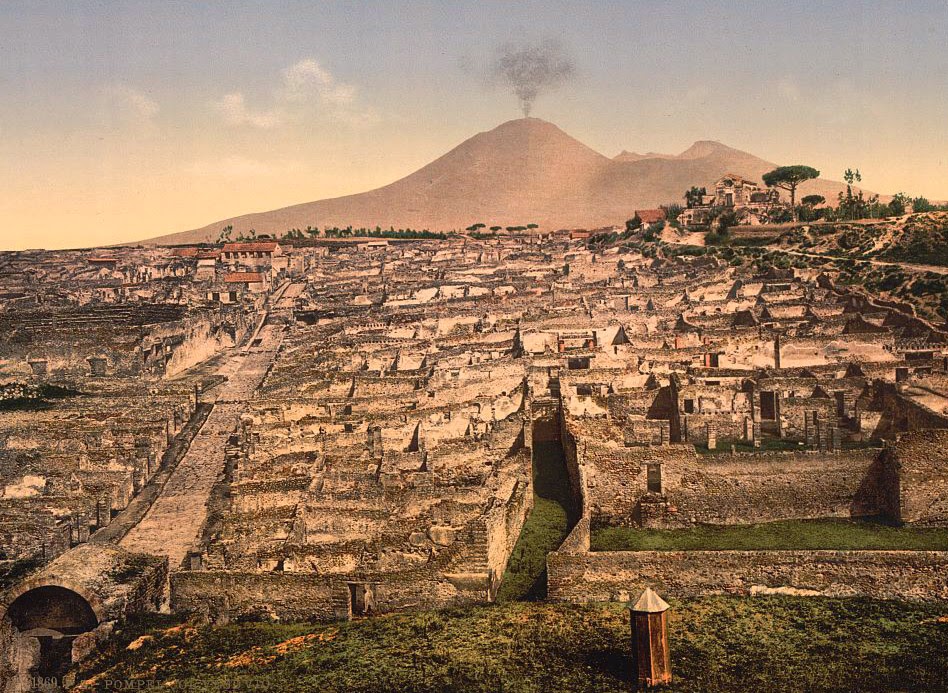

[Image: General view of Pompeii and Mt. Vesuvius; courtesy U.S. Library of Congress].

[Image: General view of Pompeii and Mt. Vesuvius; courtesy U.S. Library of Congress].

In Phys.org’s words, the sensors are being installed “to assess ‘risks of hydrogeological instability’ at the sprawling site, boost security and test the solidity of structures, as well as set up an early warning system to flag up possible collapses.”

The results are a bit like electronic eavesdropping—a kind of NSA of the ruins—only, instead of wire-tapping a single phone line, the entire city of Pompeii will be listened to from within, hooked up from one side to the other with equipment so sensitive it is normally used in waging “electronic warfare.”

[Image: The Street of Tombs, Pompeii; courtesy U.S. Library of Congress].

[Image: The Street of Tombs, Pompeii; courtesy U.S. Library of Congress].

The data will eventually be made available online for all to analyze, but it is interesting to read of a more immediate use of the sensors’ findings: Pompeii’s “security guards will be supplied with special radio equipment as well as smartphone apps to improve communication that can pinpoint their position and the type of intervention required.”

In other words, guards will receive electronic updates from the city itself while out on their daily rounds, including automated pings and alerts of impending structural failure or deformations of the ground, like some weird, semi-militarized version of ambient music, as if listening to the real-time groans of a settling city by radio.

Wire-tapping the ruins of a dead city, this mesh of electronic equipment—normally used in military surveillance operations—will thus help to preserve the archaeological site for future generations.

[Image: Fortuna Street, Pompeii; courtesy U.S. Library of Congress].

[Image: Fortuna Street, Pompeii; courtesy U.S. Library of Congress].

Like something out of Douglas Kahn’s recent book about the history of terrestrial electromagnetism and audio art, the old crumbling columns and shattered walls of Pompeii will soon find a new voice through repurposed military equipment, a weaponized seance performed on the empty streets of a place that’s more tomb than city.

[Image: The Forum, Pompeii; courtesy U.S. Library of Congress].

[Image: The Forum, Pompeii; courtesy U.S. Library of Congress].

The possibilities for interactive apps and other touristic experiences are also mind-boggling here: imagine, at the very least, being able to walk into the center of Pompeii totally alone, with nothing but your phone and some earbuds, tuning into real-time broadcasts of the shuddering masonry all around you, a wireless archaeological orchestra of bleached monuments in the sun, listening from within to the sounds of the ancient city.

Distant HAM radio enthusiasts, tuning in from attics in Indiana, spin the dial every Saturday night hoping to find Pompeii, a destroyed city on the other side of the world with its own location in the ether, whistling and purring as its architecture falls apart, room by room, a catacomb of sound and destruction.

(An earlier, different version of this post first appeared on Gizmodo).

[Image:

[Image:  [Image:

[Image:  [Image:

[Image:  [Image:

[Image:

[Images:

[Images:

[Images:

[Images: