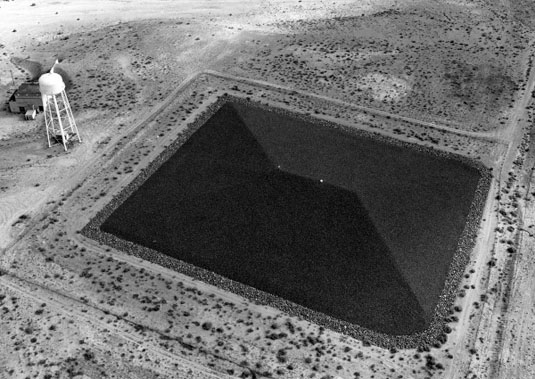

[Image: A “disposal cell,” also visible on Google Maps, courtesy of CLUI].

[Image: A “disposal cell,” also visible on Google Maps, courtesy of CLUI].

It’s always welcome news around here when a new exhibition opens up at the Center for Land Use Interpretation—even though, in this case, it displaces the excellent historical look at U.S. federal surveying with the Initial Points: Anchors of America’s Grid show.

On display now is Perpetual Architecture, which explores “uranium disposal cells in the southwest,” constructed “primarily to contain radioactive contamination from decommissioned uranium mills and processing sites. They are time capsules, of sorts, designed to take their toxic contents, undisturbed, as far into the future as possible.” More info, including visiting hours and location, is available at the CLUI website.

Meanwhile, those of you interested in this sort of thing might enjoy BLDGBLOG’s earlier interview with Abraham van Luik, a geoscientist with the U.S. Department of Energy who described in great detail the process by which sites are chosen for the task of isolating nuclear waste over geological timescales.

Just watched "Gomorra," so this feels extremely relevant. Not that it hasn't always been.

Coincidentally, this feels very relevant to me as well, as I've just listened to something about the pyramids over on 99% Invisible that was very relevant.

Weird!

It has probably been covered here before, but I would highly recommend the awesome documentary "Into Eternity" which shows the storage of nuclear waste in Finland and the implications of having to think about the incredible time scale (100,000 years) required for it to be kept away from humans, or whatever else may come in contact with it.

It's interesting to note that the very substances these structures are built to contain were the original impetus for mining uranium. An important constituent of the tailings is radium-226, which in the days before the Second World War was worth many thousands of dollars a gram. The half-life of 226-Ra is 1600 years, but it is constantly being generated by the decay of 80 000 year thorium-230.

Most fission products, by contrast, have very short half-lives : the fission process burns out instantaneously the energy which would otherwise have driven a 4.5-billion-year decay chain. As a result, after a few hundred years, spent nuclear fuel from current power reactors is less radioactive than the ore it was produced from (although the resulting diminution of the radioactivity of the Earth is negligible, since most of that is in the lower lithosphere). The components of greatest concern, in terms of biological isolation, are transuranics such as plutonium, which ought to be used in power reactors, thus avoiding the need to mine more new uranium.