A few opportunities for those of you looking for new outlets:

1) Kerb, the journal of landscape architecture from RMIT University in Melbourne, is publishing its 20th issue, on “speculative narrative” and other “fictional dispositions” in the field of landscape design. Submissions are due May 4.

[Image: Kerb 20].

[Image: Kerb 20].

Read more on their website.

2) Spend three weeks in a renovated cotton mill in the woods of upstate New York, drawing, projecting, building, and discussing architecture. Arts Letters & Numbers, run by the Cooper Union’s David Gersten, “is conceived of as: an architecture, a theater, a film, a drawing, a conversation, an action, a reenactment and a school, all inside each other.” The workshop will begin “by drawing in the landscape with the elements; fire, air, water, and earth. These explorations will be a starting point for an evolving conversation between inside and outside, between fire and film, water, theater, air, drawing, earth and architecture. The entire site will be used to explore these interactions and develop amplifying exchanges and unpredictable questions.”

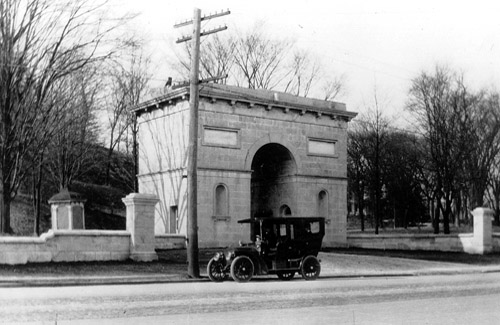

[Image: The cotton mill].

[Image: The cotton mill].

There will be daily seminars, visiting lecturers, near-continuous workshops, and don’t forget “great food.”

The photos below document a related workshop, also run by David Gersten, held in Aarhus, Denmark; while the space in upstate New York presents a different set of possibilities for work and display, a similarly immersive approach will be followed.

[Image: Photos from Aarhus Arc, led by David Gersten].

[Image: Photos from Aarhus Arc, led by David Gersten].

Applications are due May 1, and the workshop itself runs July 7–28. More information is available on the workshop website.

3) The newest issue of The State dives into the spatial imagination of “speculative geographies.”

We welcome submissions around the theme of “Speculative Geographies,” and encourage experimentation with form, transmedia, and (web)site-specific installations; critical texts, interrogative narratives, slow journalism, sensuous net-artwork, moving or still images, psychogeographic mappings, place hacking, manifestos and conversations, among others. Because of the nature of The State, please do not feel restricted by the above; please feel free to alternatively submit a wall of text.

Submissions are due April 30.

[Image: Urban Animal].

[Image: Urban Animal].

4) The Animal Architecture Awards are back with a look at the “urban animal.”

Urban areas are quickly becoming the densest concentrations of human life on the planet and with that comes the well documented positive and negative impacts to local biodiversity and ecologies. But humans are not the only urban animals—squirrels, pigeons, mice, rats, crows, raccoons, beetles etc.—all species identified as synanthropes—that “live near, and benefit from, an association with humans and the somewhat artificial habitats that humans create around them.” These are highly-urbanized non-human animals and our potential design partners.

Accordingly, “Animal Architecture wants your ideas about how synanthropic design can reshape, expand and redefine the context of urban thought and space.”

Register by May 13—and check out a few submissions to last year’s Animal Architecture Awards here on BLDGBLOG.

5) Finally, for those of you Down Under, Open Agenda is seeking “text and graphic based proposals that seek to develop research through architectural design” specifically from “graduates from a professional Australian or New Zealand degree [program] in architecture in the last ten years.” Register by May 27th.

[Image: Open Agenda].

[Image: Open Agenda].

Good luck!

[Image: Poster design by Atley Kasky of Outpost].

[Image: Poster design by Atley Kasky of Outpost].

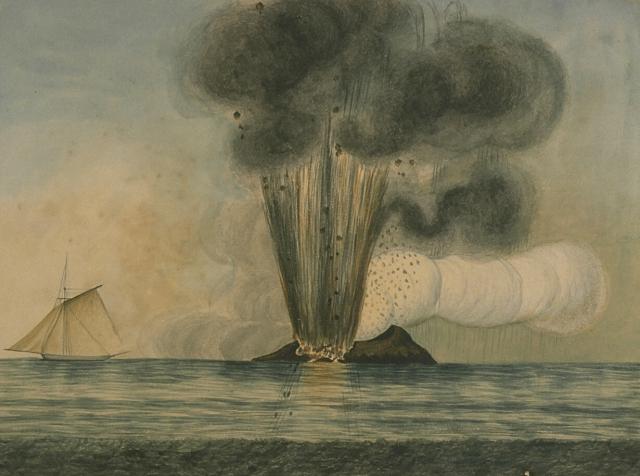

[Image: Temporary islands emerge from the sea,

[Image: Temporary islands emerge from the sea,

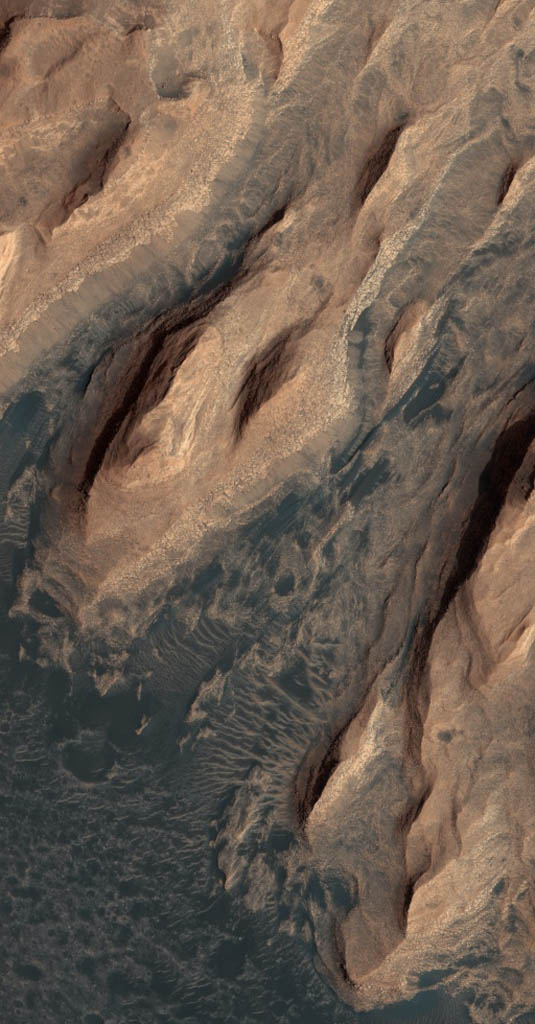

[Image: An otherwise randomly grabbed

[Image: An otherwise randomly grabbed

[Image:

[Image:  [Images:

[Images:  [Images:

[Images:  [Images:

[Images:

[Image: Piece of Nature Preserved (1973) by Haus-Rucker-Co; photo by Hagen Stier, courtesy of the

[Image: Piece of Nature Preserved (1973) by Haus-Rucker-Co; photo by Hagen Stier, courtesy of the

[Image: Via

[Image: Via  [Image: Via

[Image: Via

[Image: The ghost town of Animas Forks, Colorado, via

[Image: The ghost town of Animas Forks, Colorado, via

[Image: Gentlemen quarriers of a golden age,

[Image: Gentlemen quarriers of a golden age,  [Image: A quarry site that now “lies in the bed of the present Harlem River,”

[Image: A quarry site that now “lies in the bed of the present Harlem River,”  [Image: Nautical chart of the Harlem River, courtesy of

[Image: Nautical chart of the Harlem River, courtesy of

[Image: Manhattan Piranesi,

[Image: Manhattan Piranesi,

[Image: Building the

[Image: Building the  [Image: Building the

[Image: Building the  [Image: Checking plinths at the

[Image: Checking plinths at the

[Image: A blanket of rebar is installed inside the pit at the

[Image: A blanket of rebar is installed inside the pit at the

[Images: Building the

[Images: Building the

[Image:

[Image:  [Image: The cotton mill].

[Image: The cotton mill].

[Image: Photos from

[Image: Photos from  [Image:

[Image:  [Image:

[Image:

[Image: The plug, courtesy of Homeland Security’s

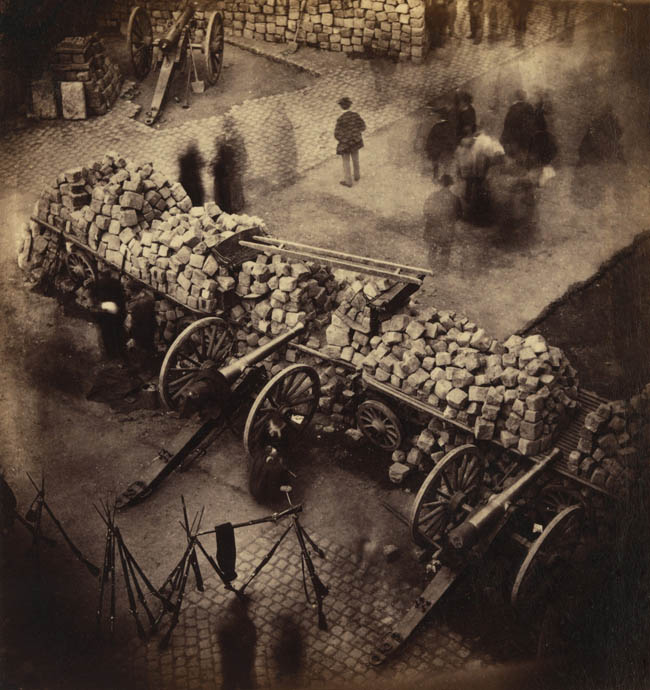

[Image: The plug, courtesy of Homeland Security’s  [Image: Paris barricade made from cobblestones (1871), photographed by Pierre-Ambrose Richebourg, via

[Image: Paris barricade made from cobblestones (1871), photographed by Pierre-Ambrose Richebourg, via