One of many fascinating details to be found in the Underground Space Center Library archives at the Canadian Centre for Architecture is something from a paper, written by a University of Minnesota law student, called “Zoning Ordinances as Obstacles to Earth Sheltered Housing: A Minnesota Perspective.”

[Image: Random basement floorplan].

[Image: Random basement floorplan].

There, amongst other key legal points, the student weighs in on what he calls the “definitional problems” that arise when traditional zoning law is applied to underground space—indeed, “whether zoning regulations apply at all to underground structures.”

Though the paper clearly focuses on the state of Minnesota, it goes as far afield as Texas; in the case of Hancox v. Peek, for instance, “a Texas Court of Appeals held that a fallout shelter which was wholly underground, except for a concrete slab which extended a mere two or three inches above the ground, was not a building—merely an appurtenance, and therefore not within the contemplation of a zoning ordinance requiring a minimum distance between buildings and adjacent property.” One can easily imagine byzantine courtroom arguments and legal appeals of the future, citing legal precedents from wartime bunker construction, domestic fallout shelters in Texas, and perhaps even subsurface mine-safety regulations in some strange Kafkaesque scenario involving, say, the late Mole Man of Hackney and his contested underground estate.

But, as it happens, my reference to mining safety is deliberate.

[Image: Random basement floorplan].

[Image: Random basement floorplan].

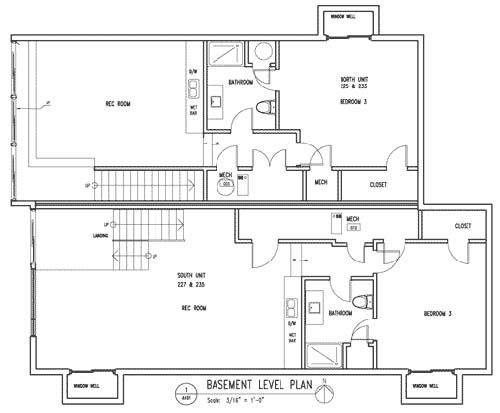

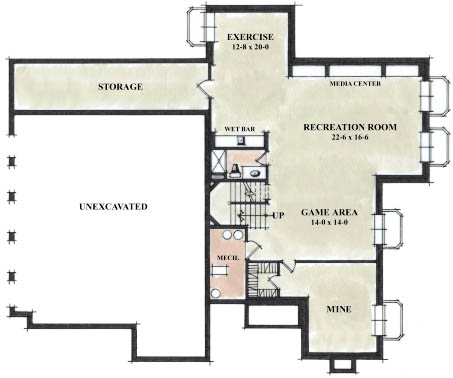

At the time of the paper’s writing—the late 1970s—underground facilities, from parking garages to hospitals and private homes, were considered so novel from the perspective of traditional Minnesota zoning law that there was no accepted legal means for how to define or describe them. These are the “definitional problems” mentioned above. “Examples,” we read, “are the broad definitions of basement and cellar… defining excavations of greater than 400 cubic yards as ‘mining’—thus requiring a special permit, and defining ‘detached dwelling’ as one ‘entirely surrounded by open space’.”

That’s worth repeating: excavations of greater than 400 cubic yards were legally zoned as mines—whether it was a parking garage or your newly renovated basement rec room.

In other words, if you lived in Minnesota in the 1960s and 70s, and you had a particularly enormous basement, inside of which you and your siblings might have watched television, you could, legally speaking, have been playing inside a mine. Whether or not this gave you permission to harvest minerals is unclear.

[Image: A continuous mining machine at work; image courtesy of Salt Union Ltd].

[Image: A continuous mining machine at work; image courtesy of Salt Union Ltd].

No lawsuit, to my knowledge, has ever been retroactively filed against Minnesotan parents, accusing them of mine-safety violations—but there is always a first time.

Nor has the reverse of this scenario—in which a Minnesotan industrial minerals magnate from St. Cloud successfully rezones his mine or quarry as a domestic basement—been, to my knowledge, attempted.

I congrats you doing work at the CCA, its nice to have intellectuals coming to Canada to do their research.

As for your last post, its a zoning condition that occurs all across Canada too. In school we also pondered the implications of building wholly underground as to bypass most zoning restrictions. I also remember a urban residential project in recent time in the UK (name fails me right now) that was completely built subterranean as to bypass the limiting setbacks of the site.

The part that interests me the most about these subterranean homes is that zoning planners don't seem to care or seem to be in a hurry to amend them.

The University of Minnesota loved to build things underground in the late 1970s and early 1980s. The Civil Engineering Building (completed 1982) is a largely underground structure; its two lower floors are 100 feet below surface level. Originally there was a mirror mechanism that directed sunlight to the lower floors — today it has fallen to disrepair and no longer functions.

See also Place v. Board of Adjustment, 42 N.J. 324 (1964), where the court held that a fallout shelter was a "structure" subject to setback regulations.

In Coober Pedy, an opal mining town in Central Australia, many residents have converted old mines into underground housing (in fact, the name of the town can be very loosely translated as 'white men in holes in the ground' in the local Aboriginal dialect.

We were told that mining within town limits is now forbidden – the holes left from mining are dangerous. But that home extension is not forbidden – and many two person homes now have dozens of rooms, and left the owners hundreds of thousands of dollars richer in the process.

Forgive me that this comment has very little to do with the article above, but it reminded me of a burglary in Leeds (Yorkshire, UK) that I'm sure you (and readers!) may appreciate for its architectural daring. Hyde Park is a poor area of terraced houses in Leeds inhabited mainly by students and as such are often targeted by burglars for laptops/televisions/games consoles etc.

But rather than another typical burglary, this one involved a much more elaborate plot. A team of burglars had rented out a house in (we presume) a fairly central location within the block, notably with a basement. When the annual Leeds Met vs Leeds University rugby match was taking place (an event that no student in Leeds would want to miss considering the rivalry of the two universities) this left all the houses in the area temporarily empty for about two hours. And in this time the team of burglars had used tunnelling equipment to work their way into each basement in the block, allowing them up into the bedrooms upstairs to gather the usual laptops etc, before disappearing off back through their original hole in their basement wall and into a van without any external signs of burglary.

Needless to say the students renting the basement rooms were all fairly surprised when they arrived home and could see a hole stretching all the way along the terrace block through their neighbouring basement walls. The police were quoted at the time saying something along the lines of 'dangerous engineering professionals'. Needless to say, the team of criminal tunnellers were never caught, and the story remains folklore to the students and police of the city.