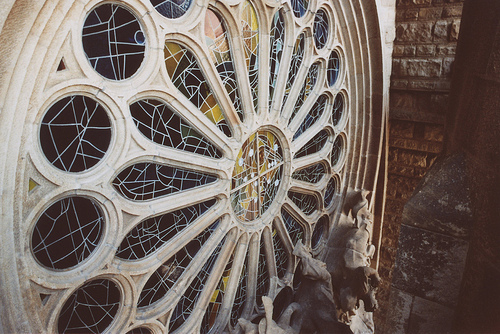

[Images: Six photographs by Danny Wills, from the often awe-inspiring sets of 475 and 194 images that he has uploaded within the past 48 hours, all taken during his recent travels through Spain; there is some great work up there].

[Images: Six photographs by Danny Wills, from the often awe-inspiring sets of 475 and 194 images that he has uploaded within the past 48 hours, all taken during his recent travels through Spain; there is some great work up there].

Month: August 2009

Architecture is always a way of envisioning our world transformed into something else

Omnivoracious, the Amazon.com editors’ blog, has just posted a relatively long interview with BLDGBLOG about The BLDGBLOG Book – and I think it turned out really well, in fact. If you’re new to BLDGBLOG, or if you simply want to know more about the motivation behind this site or The BLDGBLOG Book, then it might be worth checking it out.

From Franz Kafka to prison break films, haunted house novels to the effects of weathering on high-tech materials, Norse myths to Los Angeles traffic jams, artificial glaciers to the overlooked spatial opinions of private parking attendants, the interview really seems to run the list of things I’ve been trying to focus on here.

A brief excerpt:

For instance, what do janitors or security guards or novelists or even housewives – let alone prison guards or elevator-repair personnel – think about the buildings around them? What do suburban teenagers think about contemporary home design, when their own bedrooms are right next door to their parents – or what do teenagers think about urban planning, when they have to drive an hour each way to get to school? These sorts of apparently trivial experiences of the built environment are often far more important to hear about than simply learning – yet again – how a certain architect fits him- or herself into a self-chosen design lineage.

So perhaps we should stop talking to Frank Gehry and start interviewing valet parkers in Los Angeles – or crime novelists, or SWAT team captains. They all have an opinion about the built environment, and about the way that cities function, but no one tends to ask them what those opinion might be.

If you get a chance, check it out – and if you haven’t picked up a copy of The BLDGBLOG Book yet, definitely consider ordering one soon. And thanks!

Future Pastoral

Earlier this week I stumbled across a series of genuinely beautiful architectural prints by Nathan Freise. These were first exhibited back in July 2008 at New York’s School of Visual Arts, and it would have been a real treat to see them in person.

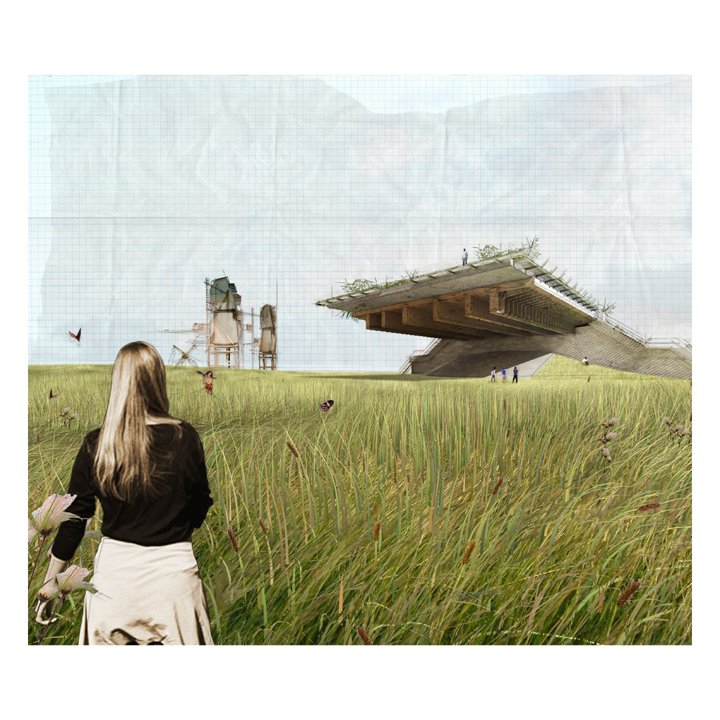

[Image: “The Garden of Machines” by Nathan Freise, from his extraordinarily well-produced Unseen Realities series; perhaps it’s Andrew Wyeth meeting the U.S. interstate highway system in a world art-directed by Guillermo del Toro].

[Image: “The Garden of Machines” by Nathan Freise, from his extraordinarily well-produced Unseen Realities series; perhaps it’s Andrew Wyeth meeting the U.S. interstate highway system in a world art-directed by Guillermo del Toro].

Nathan, of course, is the brother of Adam, and the two of them together – as the Freise Brothers – also directed a short film called The Machine Stops, whose website is also worth a visit if you get the opportunity.

[Image: “The Garden of Machines (Dwell)” by Nathan Freise, from Unseen Realities; this one brings to mind some 22nd-century Charles Darwin watching the machine-birds of tomorrow’s eco-motorways, where billboards become breeding grounds for species we’ve never seen before].

[Image: “The Garden of Machines (Dwell)” by Nathan Freise, from Unseen Realities; this one brings to mind some 22nd-century Charles Darwin watching the machine-birds of tomorrow’s eco-motorways, where billboards become breeding grounds for species we’ve never seen before].

The specific images here are described as follows:

Freise’s series of inkjet prints depict experimental architecture projects. His hybrid illustrations combine multiple forms of media – ink, graphite, photography and marker – with computer graphics. Freise’s representations of utopian worlds question our current conditions of suburban sprawl and urban master-planning.

They are absolutely worth checking out in their original, full size; click through to the Freise Brothers’ website and open them in their full, 1000-pixel glory.

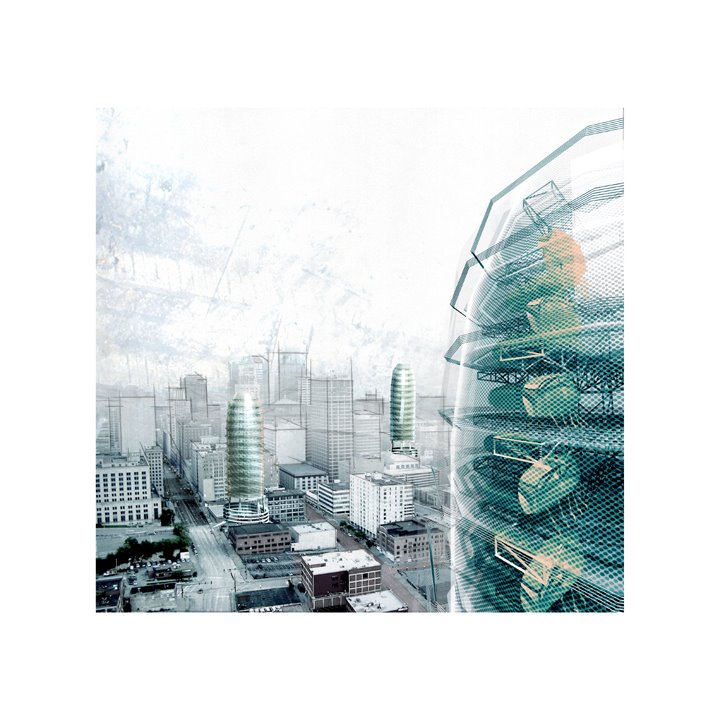

[Image: “Transience (The Nomads)” by Nathan Freise, from Unseen Realities].

[Image: “Transience (The Nomads)” by Nathan Freise, from Unseen Realities].

What I like so much about these is not just their technical quality but their combination of pastoral, near-Edenic landscapes with semi-unconstructed megastructures straight out of scifi. Technicolor screenprints of the architectural future!

A new Hudson River School arises, in which the flowering concrete foundations of incomprehensible buildings can be seen, scattered throughout the wild valleys, glinting with fragments of steel as the sun goes down.

[Images: “Transience (Decay and Renewal)” by Nathan Freise, from Unseen Realities].

[Images: “Transience (Decay and Renewal)” by Nathan Freise, from Unseen Realities].

In any case, hopefully someday someone will commission him to make more.

Excavatory Improv

[Image: From Sean Regan’s final project at Urban Islands 2009].

[Image: From Sean Regan’s final project at Urban Islands 2009].

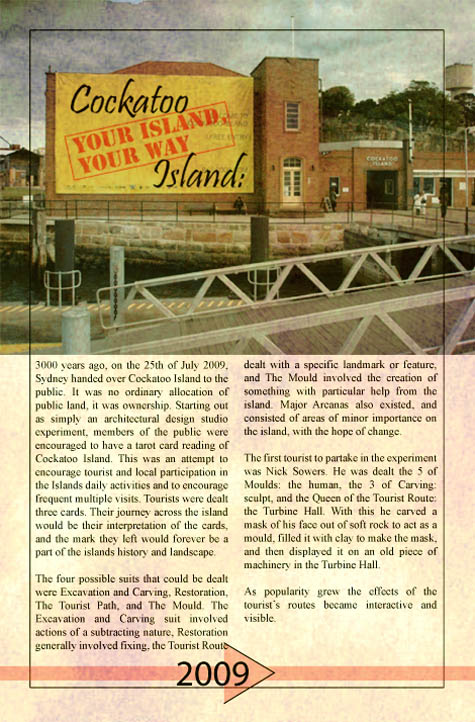

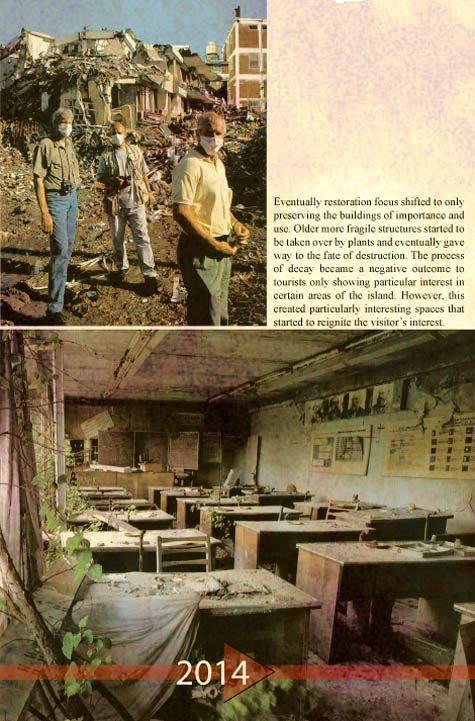

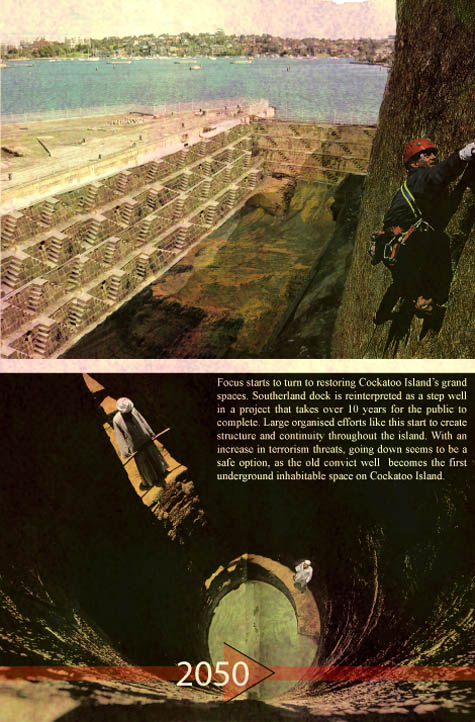

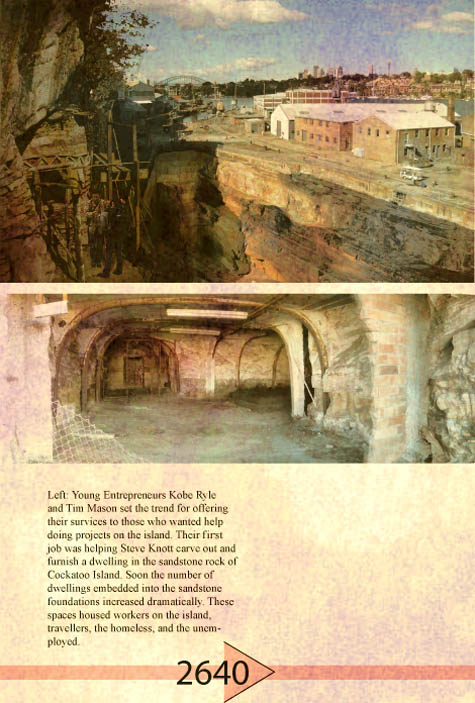

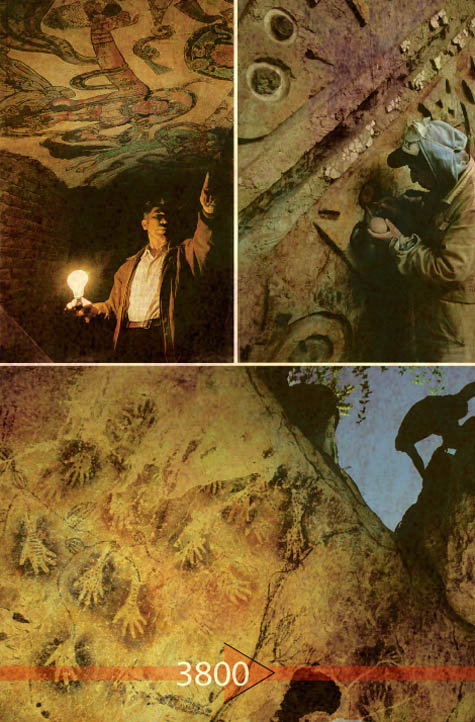

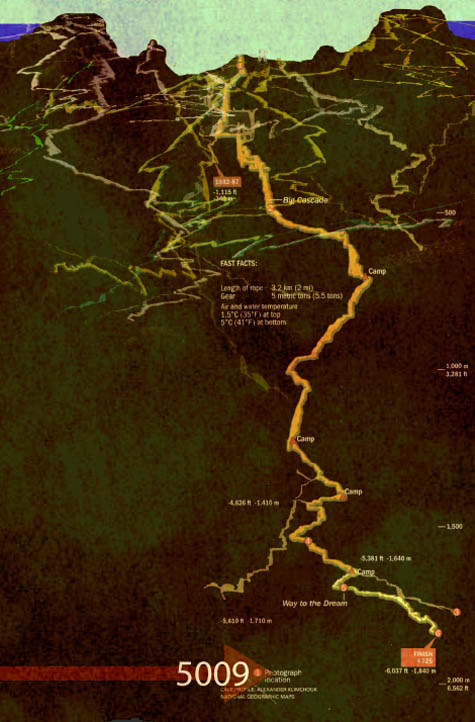

For his final project at Urban Islands – hosted the other week in Sydney and previously discussed here, here, here, here, and elsewhere – Sean Regan produced a heavily-illustrated fake article for a distant-future issue of National Geographic.

[Image: Image and text from Sean Regan’s final project at Urban Islands 2009].

[Image: Image and text from Sean Regan’s final project at Urban Islands 2009].

Piecing together found imagery to create his own narrative exploration of Cockatoo Island, Sean addressed the following question: What would happen to the island if it was no longer historically preserved but deliberately, often violently, altered by the tourists who came to visit it?

[Images: From Sean Regan’s final project at Urban Islands 2009].

[Images: From Sean Regan’s final project at Urban Islands 2009].

That is, what if tourists were given a more or less complete freedom to carve, excavate, blast, construct, drill, tunnel, and alter their way across the island landscape?

[Images: From Sean Regan’s final project at Urban Islands 2009].

[Images: From Sean Regan’s final project at Urban Islands 2009].

Because of the nature of the studio itself – which was based around the idea of random program generation through the design and distribution of Cockatoo Island-themed “Tarot” cards – this would take the specific form of tourists being handed a series of cards upon arrival at the island.

On these cards would be actions, sites, tools, materials, and so on that the visitors would be free to interpret – acting out their conclusions in physical form through often drastic and completely unregulated interventions into the structure of the island itself.

[Images: From Sean Regan’s final project at Urban Islands 2009].

[Images: From Sean Regan’s final project at Urban Islands 2009].

Over thousands of years, then, Cockatoo Island would be transformed through tourist excavations into an increasingly subterranean mazescape of new, improvised passageways – think of it as a kind of geotechnical free jazz, burrowing its way through new forms and structures of geology.

The walls themselves become gradually covered in post-aboriginal myths and cave paintings, and anthropologists from around the world come to Sydney to study the altered massing of Cockatoo.

It was pointed out in the final studio crit, as exhaustively documented by fellow participant Nick Sowers over on Archinect, that this sort of anything-goes approach to managing Cockatoo Island’s future is diametrically opposed to the strange and disappointing historical stasis in which the island is currently trapped.

The island needn’t be frozen in place, in other words, becoming a museum of its last role (an industrial shipbuilding yard); it could, in fact, be endlessly transformed, over decades, centuries, and even thousands of years, to become a palimpsestic reduction of eras, needs, and fleeting intentions.

After all, it was pointed out, that’s exactly what Cockatoo is already: a delirium of excavations. It is sliced through with tunnels. Its cliffsides are artificial. Its shorelines have been expanded. Its native species have been replaced.

But it’s as if Cockatoo’s preservationists have been saying, “We will celebrate this island… by transforming it into the very thing it is has never been: static.”

In this context, perhaps Sean’s project isn’t merely a speculative fantasy of permanent excavation – proposing a future state of geological amnesia in which constant, superficial erasure reacts mindlessly to the past – but a necessary demonstration of how historic preservation often fails to reveal the very essence of the sites it seeks to celebrate.

[Image: Cockatoo Island is now a warren of artificial caves extending for kilometers into the earth’s surface below. From Sean Regan’s final project at Urban Islands 2009].

[Image: Cockatoo Island is now a warren of artificial caves extending for kilometers into the earth’s surface below. From Sean Regan’s final project at Urban Islands 2009].

In any case, the sandstone plateau of the island, the project suggests, will eventually be scraped away to levels far below the waves of Sydney Harbor, requiring the construction of massive ring dams to hold back the sea. The entire island is thus placed into a state of dry dock.

By the year A.D. 5009, Cockatoo is nothing more than an opening into the underworld, the island’s terrestrial presence having been replaced with the thousands of tunnels now spiraling away into the earth below.

Of course, the images that appear here have been deliberately aged to look as if they were found in an excavation several thousand years from now, but Sean’s collaging skills, disguised beneath those stains and discolorations, are extraordinary. It was a genuine pleasure to watch this project take shape over the second half of our two-week studio.

Graphic Analysis

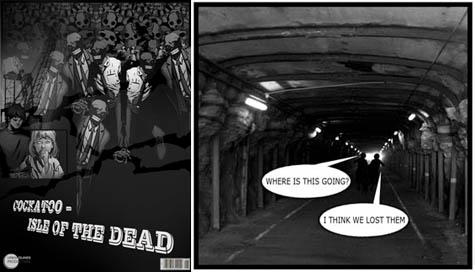

Another noteworthy project from the recently completed Urban Islands design studio down in Sydney was Yael Kaufman’s short horror comic book, Cockatoo: Isle of the Dead.

[Image: Scanned & collaged comic book images appear alongside a photo from the Dogleg Tunnel on Cockatoo Island by Yael Kaufman, Urban Islands 2009].

[Image: Scanned & collaged comic book images appear alongside a photo from the Dogleg Tunnel on Cockatoo Island by Yael Kaufman, Urban Islands 2009].

Kaufman’s Isle of the Dead tells the story of three friends who have gone out for an evening joyride on a boat in the Sydney Harbor – only to capsize, finding themselves split up, disoriented, and washed by currents onto the dark shores of Cockatoo Island.

[Image: From Cockatoo: Isle of the Dead by Yael Kaufman, produced for Urban Islands 2009].

[Image: From Cockatoo: Isle of the Dead by Yael Kaufman, produced for Urban Islands 2009].

There, two of the them get back together – only to stumble upon an industrial-scale project for the resurrection of the dead. The island’s former inhabitants – from prison wardens and ship captains to young reform school boys and girls – are being brought exhumed en masse and back to life by a horrifically repurposed shipbuilding crane.

[Image: More collaged comic book images and photos from Cockatoo Island by Yael Kaufman].

[Image: More collaged comic book images and photos from Cockatoo Island by Yael Kaufman].

It’s a short tale of architectural history wrapped up as a tongue-in-cheek horror comic – and it’s even got a trick ending…

Of course, the reason for putting together this sort of project came from the motivating constraints of the studio itself.

As mentioned on BLDGBLOG before, the studio’s overall conceptual goal was to create 78 playing cards (designed by the students themselves and inspired both by Tarot cards and by Brian Eno’s Oblique Strategies deck); each card was based on one of the key sites, structures, events, spaces, and/or personalities from the incredible insular history of Cockatoo.

These were then randomly distributed amongst the students, who were required, finally, to produce individual design projects based upon the cards that they had received.

Kaufman was dealt The Crane, Tides & Currents, and the island’s Former Inhabitants – and so the narrative that she assembled from those elements resulted in the comic book of which we see a few spreads here.

During the process of putting it all together, during the extremely limited time frame of only four days in studio, Yael and I looked at House, a wordless graphic novel by Josh Simmons, as well as an English-language version of MetroBasel, a narratively elaborate graphic novel and site analysis produced by Jacques Herzog, Pierre de Meuron, Manuel Herz, and Ying Zhou of ETH Studio Basel. Of course, if I had it with me in Australia, I would also have pointed Yael toward BIG’s recent Yes Is More exhibition catalog/comic book.

But whether or not you like the idea of using horror stories as a way to explore a given architectural site’s history, the graphic novel as an analytic tool is something that deserves greater strategic attention – as well as something that appears quite rapidly to be catching on as a genuine option.

[Image: From Cockatoo: Isle of the Dead by Yael Kaufman, produced for Urban Islands 2009].

[Image: From Cockatoo: Isle of the Dead by Yael Kaufman, produced for Urban Islands 2009].

After all, if you can open up the range of media – and even, in Yael’s case, the range of genres (why not a love story? why not a pop song? why not a murder mystery?) – through which we discuss, argue about, and analyze architecture, then surely the range of participants in architectural conversations will simultaneously expand as well.

Put another way: comic books and graphic novels – and, yes, horror stories – are going to be written and produced, whether or not architects play any role whatsoever.

Why not, then, at the very least, slip some interesting ideas and structures into those narratives and help to expand the popular image of what constitutes architectural design?

On a sunny morning in Cairns, I’m flying back into the range of internet reception, having just spent some time up in Cape Tribulation and Daintree National Park.

Cape Trib is interesting for a variety of reasons, including the fact that it is off of the national power grid – everything is lit either by generators or solar power – and it is also where the paved road ends; the famous Bloomfield Track extends north toward Cooktown, through the imaginations of Range Rover fans, and up to connect with other dirt roads along the bewilderingly remote Cape York Peninsula, where abandoned WWII airfields sit amidst empty fuel drums being slowly entombed by jungle.

So I’ve been totally absent from posting for the past week, but we were staying on an exotic fruit farm, watching the lizard who lived in our light fixture, listening to Main against an acoustic backdrop of endless tree frogs, within walking distance of two World Heritage sites: the coastal intersection where the Great Barrier Reef meets the mangroves of Daintree on a small beach covered in stumps of coral, semi-submerged beneath tide pools. We even saw a cassowary.

But BLDGBLOG will be in Brisbane all week now, within the curtain of the internet, and I’ve got a million and one awesome links to share – such as the person who now lives totally alone inside a brand new Florida high-rise and the “rubber village” built for military training in Israel. More soon!

Island of Future Airships

As the previous post suggested, a number of great projects came out of this year’s Urban Islands.

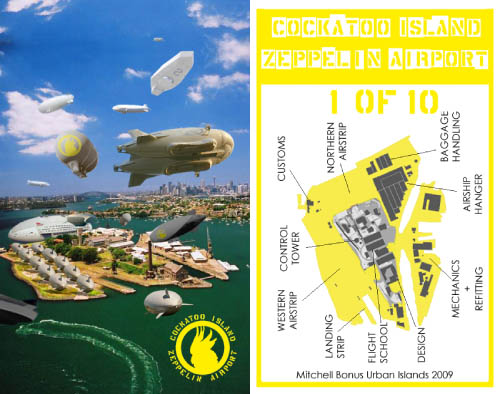

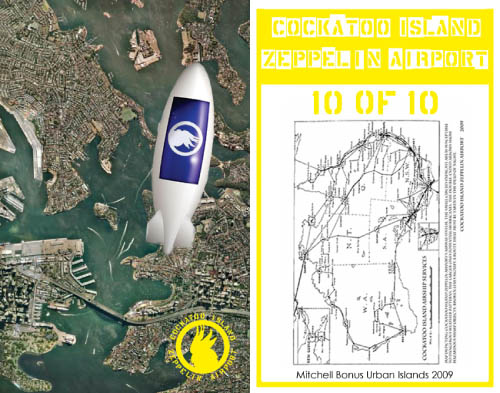

[Image: The front and back of an architectural trading card, designed by Mitchell Bonus for Urban Islands 2009].

[Image: The front and back of an architectural trading card, designed by Mitchell Bonus for Urban Islands 2009].

I’ve mentioned it before, of course, but Urban Islands is a biannual architecture studio hosted out on Cockatoo Island in Sydney Harbor. For two weeks, students and their visiting international instructors – I had the huge pleasure of serving as an instructor this year – explore the spatial possibilities of Cockatoo’s abandoned landscapes.

For now, focusing solely on the work of my own students, I want to highlight five or six particularly interesting responses to the design brief (a brief I’ll describe in a later post).

The previous post was one project; the following project is by Mitchell Bonus.

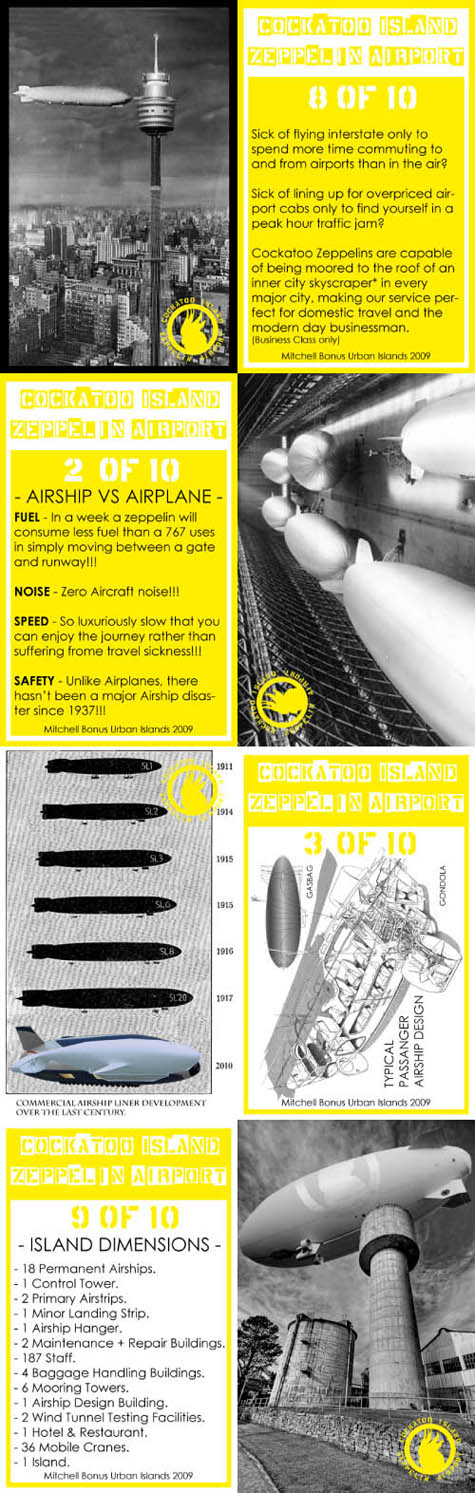

Tongue firmly in cheek, Mitchell has called for Sydney’s apparently much-needed second airport to be built out on Cockatoo in the form of a solar-powered zeppelin field.

The style of his pitch, however, was strategically ingenious, well worth both study and emulation elsewhere.

Acting on the assumption that, if you want to see a new building or project take shape, then you have to stop relying on design competitions, architecture blogs, or industry publications to get the word out – that is, you need to find another way to convince the public that your design should exist, making its material realization seem more like an afterthought – Mitchell created a series of trading cards, modeled after sports cards.

He then sealed, laminated, and stuck the cards inside bags of potato chips, cigarette packs, and boxes of morning cereal.

The idea was thus that people would open up a bag of smoky bacon-flavored chips and find an architectural proposal awaiting them.

Inside their morning oat bran would be a trading card-sized vision of the future. Falling out of the cigarette box as they light up on the sidewalk would be a portrayal of some strange island future yet to come.

[Image: The fronts and backs of four architectural trading cards, designed by Mitchell Bonus].

[Image: The fronts and backs of four architectural trading cards, designed by Mitchell Bonus].

After all, why not skip Archinect, ArchDaily, Inhabitat, and Dezeen altogether and simply mass-produce trading cards of your own speculative building plans?

Then just hide those cards inside cereal boxes and wait till the ideas trickle out, burning into the collective cultural consciousness.

Gradually, it will dawn on people that, of course, there should be a new airport for zeppelins out on Cockatoo Island – or of course there should be aerial gondolas traversing Manhattan, or of course there should be a vast wheel of glass rooms, fourteen hectares in diameter, rotating over the rain forests of Papua New Guinea.

It’s like subliminal advertising for a parallel future.

Why not slip these architectural speculations into pop culture at large? Why not bypass clients and experts and just bring your vision to everyone?

Isn’t that what Hollywood set designers and concept artists have been doing all along?

[Image: Four more architectural futures cards, designed by Mitchell Bonus].

[Image: Four more architectural futures cards, designed by Mitchell Bonus].

Mitchell’s project – executed in less than one week (as with all the projects that came out of my studio) – was thus presented simply as a bunch of sealed chip packets, cigarette boxes, and so on. Viewers of his presentation were handed a bag, some cigarettes, or a cereal box and, as they opened up their personal booty, they found not just an edible lunchtime snack but a well-produced act of architectural speculation.

How incredibly interesting would it be to find that, in every box of Total or, hiding at the bottom of every canister of oatmeal you open, new visions of the cities around us are patiently hiding…?

A whole new urban redesign of Tokyo awaits anyone who buys a bucket of popcorn at the start of 2012.

[Image: The front and back of one card by Mitchell Bonus, from Urban Islands 2009].

[Image: The front and back of one card by Mitchell Bonus, from Urban Islands 2009].

It’s a genuine challenge: publish your next architectural project not as a short article in Log, or as a press release on Dezeen, but as a series of trading cards hidden inside popular consumer goods all over the world.

Slip your vision of the future into mass consciousness both slowly and subliminally.

See what happens.

The Missing Buildings of Cockatoo Island

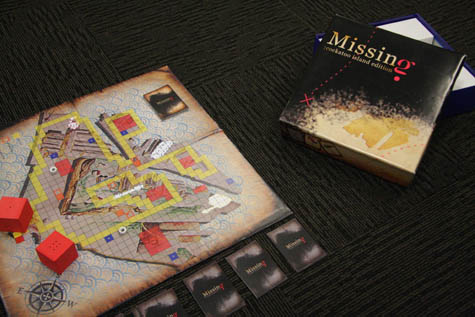

[Image: Playing Tristan Davison’s Missing: Cockatoo Island Edition].

[Image: Playing Tristan Davison’s Missing: Cockatoo Island Edition].

I’m excited finally to look back at some of the work produced by my students at Urban Islands last month in Sydney, not only to bring them much deserved attention but to show how the course itself worked out.

So, with the caveat that it has been extremely difficult for me to find reliable internet access here, and that this will only get worse over the next ten days as my wife and I head north into Daintree National Park, I wanted to take advantage of some blazing wifi to start a review of the studio’s most stimulating projects.

Here, then, kicking things off, is an entire board game, called Missing: Cockatoo Island Edition, invented, painted, and produced in less than a week by Tristan Davison.

Missing uses Cockatoo Island – the abandoned industrial site, former shipbuilding yard, and derelict prison in the Sydney Harbor that formed the site of Urban Islands – as its primary setting and game-play environment.

[Image: Missing: Cockatoo Island Edition by Tristan Davison].

[Image: Missing: Cockatoo Island Edition by Tristan Davison].

The object of the game is to re-assemble the missing buildings of Cockatoo. Players progress by strategically accumulating Action Cards and Building Cards, with the game concluding atop the island’s central sandstone plateau.

Cockatoo, for those of you who have not visited the site, is an island somewhat famously denuded of many of its former historic structures. Indeed, the island’s lost buildings are some of its most conspicuous features, their interiors still framed with a grid of iron rails in the flattened ground.

[Images: Building Cards from Tristan Davison’s Missing: Cockatoo Island Edition, produced in less than one week].

[Images: Building Cards from Tristan Davison’s Missing: Cockatoo Island Edition, produced in less than one week].

If it’s not visibly obvious, by the way, I should say that Tristan is jaw-droppingly talented, producing this entire game and many other pieces over the course of Urban Islands right there in the studio, using watercolor and ink. I was able actually to watch as many of these were outlined and colored.

[Images: Action Cards from Missing: Cockatoo Island Edition].

[Images: Action Cards from Missing: Cockatoo Island Edition].

The board itself is incredible, for instance, layering the pathway of the game atop an aerial view of Cockatoo Island and including various safety zones that can be exploited by players along the way.

[Images: The board of Tristan Davison’s Missing: Cockatoo Island Edition].

[Images: The board of Tristan Davison’s Missing: Cockatoo Island Edition].

Over the coming weeks, expect to hear more about the basic interpretive mechanism at work behind the studio, which will help to explain why Tristan produced a board game in the first place. For now, the sheer handiwork on display here, and the rapid evolution of what were basically improvised game rules, continues to amaze me.

Stay tuned for more student projects from Urban Islands!