Easily some of the best books of architectural history to be published in the last few years can be found in a series called the Wonders of the World, edited by Mary Beard.

Because I’ll be posting part one of a two-part interview with Beard tomorrow morning, I thought I’d introduce BLDGBLOG readers to the Wonders of the World series and kick off my own (short) series of book reviews about each of the published titles.

As it is, I’ve read every book in the series – and I’m impatiently waiting for more.

In a nutshell, the Wonders of the World describes itself as “a small series of books that will focus on some of the world’s most famous sites or monuments.”

Their names will be familiar to almost everyone: they have achieved iconic stature and are loaded with a fair amount of mythological baggage. These monuments have been the subject of many books over the centuries, but our aim, through the skill and stature of the writers, is to get something much more enlightening, stimulating, or even controversial, than straightforward histories or guides.

So it may not be the place to go if you want to read about Archigram’s Walking City; but if you want a quick shot of archaeology and architectural history, and if you’re a fan of, say, the Parthenon, or the Alhambra, or the Colosseum, or even London’s St. Pancras Station – or the Rosetta Stone – then it’s an absolutely fantastic series to pick up.

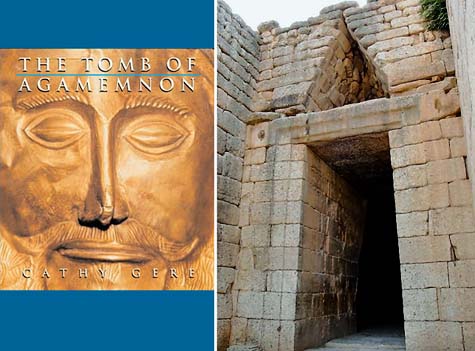

In preparation for tomorrow’s interview, then, I’ll start with a quick look at the book that first hooked me: The Tomb of Agamemnon by Cathy Gere, one of the most exciting things I’ve read in years.

In preparation for tomorrow’s interview, then, I’ll start with a quick look at the book that first hooked me: The Tomb of Agamemnon by Cathy Gere, one of the most exciting things I’ve read in years.

Ostensibly an armchair introduction to the Tomb of Agamemnon – a Mycenean shaft grave discovered in 1876 by the flamboyant amateur German archaeologist Heinrich Schliemann – the book is really a study in European culture and the political stakes inherent in archaeological interpretation and discovery.

Schliemann, who presented himself through “a syrupy blend of Homer and Hollywood,” and who developed quite a knack for media hype, transformed his somewhat accidental discovery into a de facto origin point for modern European self-identity.

The tomb was not just a hole in the ground, in other words, but a place through which Europe could explain itself, achieving narrative control over the archaeological past and rooting itself in a much more glorious version of what then passed for its history. Starting with the Greeks, she writes, “historians and dramatists reinvented the Trojan War and Agamemnon’s horrible destiny time and time again, in an increasingly desperate effort to understand and control their own violent history.”

On another level, Schliemann’s discovery only intensified the already politicized stakes of Mediterranean archaeology; his deliberately spectacular excavations were part of a much larger media project, Gere writes, that “represented a symbolic reclamation of the monument from the Ottoman [Empire],” then the dominant power in the region.

For every site uncovered, that is, with the imaginative help of story-telling archaeologists and the enthusiastic newspaper editors who cheered them, Europe came into its own.

It could project its own wished-for history onto the dusty screen of archaeology.

The book is compulsively readable, and it’s also short: I started reading it one afternoon and had finished it by that evening.

The book is compulsively readable, and it’s also short: I started reading it one afternoon and had finished it by that evening.

Though it’s a history of the grave and of the grave’s discovery, it’s also an eye-popping look at the interpretive difficulties associated with how we dig up the past.

At several points, Gere ridicules what she calls the “genre of mytho-anthropology” – her term for how the past can be mis-used in the service of heroically re-narrating, and thus justifying, the present order.

As the great tide of Christian faith receded, a wave of archaeologically inspired origin myths swept in to replace it, every nation and group racing to rewrite the Book of Genesis in the image of its own interests.

Newly excavated and insufficiently understood “icons of antiquity” were thus “made to bear all the fears and desires of modernity.”

This particular form of mytho-anthropology, Gere suggests, exhibited its most extreme tendencies in the historical era beginning with, say, the birth of Lord Byron and ending with the death of Adolf Hitler, and it is Gere’s description of this politically volatile time period that makes her book so extraordinary.

She explores how a lost golden age of Homeric warriors – sailing the high seas, declaring war, hoarding treasure – became a referential presupposition for nearly all arguments of European nationalism – particularly, we read, in the case of Friedrich Nietzsche and the German military commanders who later read him.

In the early years of the 20th century, Gere explains:

Europe filled up with neurasthenic young scholars, innocent of the horrors of combat, marshalling archaeological evidence in the support of their dreams of blood and empire. War was repeatedly proclaimed as physically and morally desirable, an antidote for decadence and a prescription for spiritual renewal.

These were the “classically educated young men who went to meet the horrors of war at Gallipoli.”

Things only got worse when the Nazis came to power.

By the time of Hitler’s ascendancy, a Teutonic Mycenae had been completely assimilated into the crackpot mixture of archaeology, mythography and so-called ‘racial science’ that provided German fascism with its own tailor-made prehistory.

Nazi field commanders marshalled their own archaeological evidence for Aryan superiority, sending morally deluded and historically misinformed storm troopers marching south toward Athens.

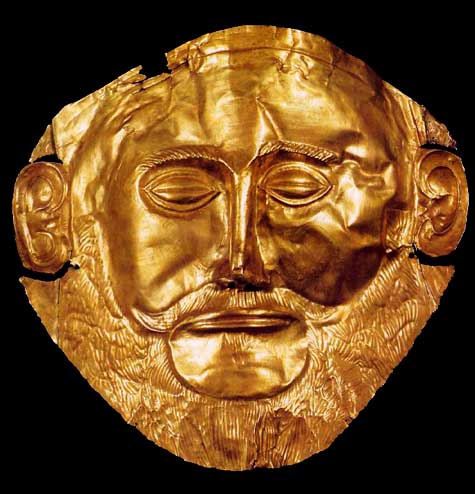

[Image: The “mask of Agamemnon”].

[Image: The “mask of Agamemnon”].

In any case, I could go on and on about the book. Instead, I’ll just say that it offers an intellectually refreshing and beautifully explained – if also sinister – angle from which to view the ideological construction of modern Europe, and the whole thing is told from the otherwise often dry perspective of archaeology.

In fact, it’s difficult to over-emphasize how exciting I found the book to be. I’m not entirely sure I’m kidding when I say that, had I read Gere’s book as a teenager, I might have become an archaeologist. Or at least a classicist.

And it will probably horrify Gere to hear me say this – because this implies that I completely misread the whole book – but The Tomb of Agamemnon falls somewhere between Indiana Jones and the most high stakes university lecture course you’ve ever taken – and it made me an absolute addict for the Wonders of the World.

And it will probably horrify Gere to hear me say this – because this implies that I completely misread the whole book – but The Tomb of Agamemnon falls somewhere between Indiana Jones and the most high stakes university lecture course you’ve ever taken – and it made me an absolute addict for the Wonders of the World.

More reviews coming soon! For now, stay tuned for tomorrow’s interview with Mary Beard.

Highly recommended: The Tomb of Agamemnon by Cathy Gere

I wonder if she talks about the California connection? Heinrich Schliemann made his (second) fortune in the California gold rush and went to Greece to make his legacy as an amateur archeologist where he found amazingly well preserved gold artifacts. Greece will not allow the gold in these pieces to be checked for place of origin. Hmmm

The Tomb of Agamemnon is a remarkable place whether the gold is authentic or not.

Here’s The Sesquipedalist’s review of the St. Pancras station book and here’s a brief extract.

The golgen mask you show is not Agamemnon as it was believed by Schielmann. It´s now on the National Museum at Athens and the explanation is quite clear: it belongs to a different king.

The photo on the right is not from Agamemnon grave, that is inside the walls of Micenas (on your right as you walk in) but of Athreus, two hundred meters down the road. It is more spectacular indeed from a Hollywood point of view,but confussion is not possible

This is indeed a great book. Bought it for three dollars 🙂 Thanks for posting about these great series!!