There’s a great new article in New Scientist about what the surfaces of other planets – with their variable air pressure and chemical humidities – might actually sound like.

Unfortunately, the article is subscriber-only, so I’ll have to summarize a few of its more interesting points.

The basic trouble, the article says, is that we haven’t sent microphones to many of the places we know so well visually.

The basic trouble, the article says, is that we haven’t sent microphones to many of the places we know so well visually.

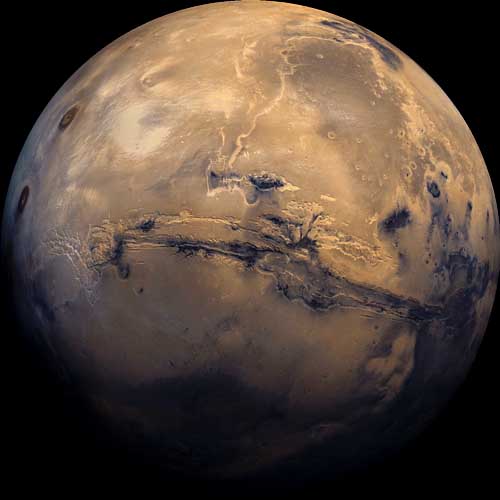

The Mars rovers, for instance, those wheeled landscape photographers whose work is destined to appear in tomorrow’s art history textbooks, “are oblivious to the soundscape of Mars.” After all, with no sensors to hear with, “they can’t hear the buzz of grit whirling around in dust devils, the rumbles of Martian thunder, or even the noise of their own wheels crunching across the dusty plains.”

We could be listening to literally extraterrestrial soundscapes on our iPods, riding through Manhattanite subway tunnels:

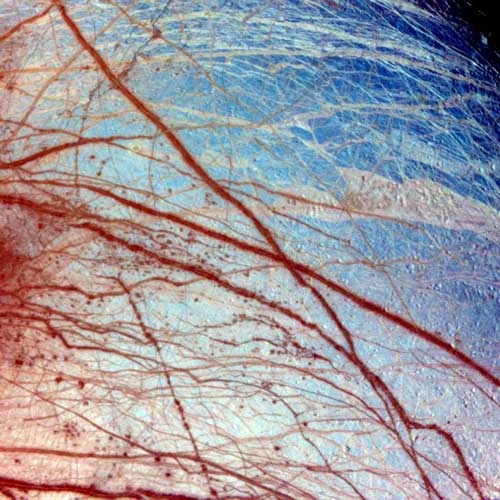

Imagine listening to babbling brooks of methane on Titan, or hearing deep thunder booming through Venus’s dense, noxious atmosphere. Or what about the creaking and groaning of ice on Jupiter’s satellite Europa, which could reveal whether the moon’s frigid exterior hides a warm ocean, hospitable to life?

But acoustics play second fiddle in most scientific investigations of other planets.

Our heavens are silent.

New Scientist points out that microphones “are usually smaller, lighter, cheaper and less power-hungry” than are cameras – imagine live-streaming the winds of Venus on your car radio, driving past Spudnuts! – but this very simplicity “may have had the adverse effect of underselling them as instruments able to deliver subtle and rich scientific information.”

Our sonic understanding of other planets is thus rather lacking – leaving us, more or less, to guess.

Call it speculative acoustic planetology.

[Image: The canyonlands of Mars; courtesy of NASA].

[Image: The canyonlands of Mars; courtesy of NASA].

So it may not immediately be obvious that things will literally sound different on other planets; but atmospheric chemistry and air pressure – or the complete lack thereof – are two major factors in the transmission of sound waves.

For instance, because “Mars’s atmosphere is much thinner than the Earth’s – the average distance between molecules is about 120 times greater – sound waves attenuate very quickly.” This has the following horror movie-like effect:

While a typical scream on Earth might still be audible a kilometre away, it would only travel about 16 metres on Mars.

This “low sound speed” would also “lower the pitch of your voice” – and give burgeoning screenwriters something to consider.

[Image: A stunning view of Venus, which looks more solar than planetary; courtesy of NASA].

[Image: A stunning view of Venus, which looks more solar than planetary; courtesy of NASA].

On Venus, meanwhile, “sulphuric acid rains down through a CO2 atmosphere with a crushing surface pressure 90 times greater than Earth’s.” A Soviet lander actually brought microphones there in 1982 – picking up “deep rumbles that might have been thunder” – but we have no real idea of what Venus actually sounds like.

We can speculate, however, using some kind of computer program, that “only low-frequency sounds carry well in the crushing CO2 atmosphere,” nearly cutting treble altogether.

It’s a planet perfect for hip-hop.

[Image: The Earth’s moon].

[Image: The Earth’s moon].

The article goes on to explain how the crust of the Earth’s moon is almost constantly groaning with “stresses and stains… due to the tidal forces of the Earth’s gravity,” and that there are a surprising number of “quakes triggered as heat from the sun swell[s] the moon’s crust.”

But what do these moonquakes sound like?

Titan, meanwhile, one of Saturn’s moons, actually has been heard before: a microphone attached to the Huygens probe, in 2005, “recorded the whistle and whoosh” of the probe’s own distant arrival.

It’s worth pointing out, in a brief but fascinating side-note, that drops of methane “about a centimetre wide” rain down onto the surface of Titan seven times slower than rain falls here on Earth. Imagine thunderstorms in bullet-time…

In any case, Titan’s atmosphere is actually “a factory for complex hydrocarbons.” The sky thus has “all this photochemistry going on,” one scientist is quoted as saying, with the result that Titan’s surface is dotted with “dark hydrocarbon lakes” – and these lakes will probably be bubbling, we read, and each bubble will probably “pulsate like a vibrating bell” when it bursts.

The acoustic effect of this would be like “having a chorus of little bubbles each ‘plinking’ at its own pitch,” and it would all sound rather “robotic.”

[Image: The cracked icy surface of Europa].

[Image: The cracked icy surface of Europa].

Finally, Europa, one of Jupiter’s moons and a celestial body long suspected of hosting life, is covered with a shell of ice. That ice, however, is constantly compressed by Jovian gravity, causing huge fissures and breakages – with, I’d think, spectacular, micro-continental bursts of atonality and noise.

But who knows?

First, we have to get a microphone there to find out.

Personally, I’d love to hear music that’s been deliberately tuned for alien atmospheres – slow, shuddering drones, or crystalline symphonies of accelerated acoustics. Even more, I’d love to read an acoustic analysis of different landscapes here on Earth: how far a scream propagates in the gardens of Versailles, for instance, or in the new Orange County Great Park. Or whether your voice sounds deeper in the deserts of Utah. Or whether you can unexpectedly overhear people talking far away, on some humid curve in the Parisian Seine.

It’s the science of acoustic planetology.

There was a microphone attached to the ill-fated Mars Polar Lander, but that sadly crashed into the surface of Mars some years ago, the casualty of some faulty landing software.

I’ve had a look at the instruments available on the recently launched, aptly-named Phoenix lander, which in some ways is a bug-fixed re-run of the previous lander, but unfortunately that doesn’t appear to have the microphone included. So your dreams of tuning into the sounds of Mars may have to wait a little while longer…

It sounds awesome and lovely already.

In 1969 Lucia Pamela recorded an entire album on the moon – and she played every instrument in the multi-track recording. Claimed her voice sounds so deep on the album (Into outer Space with Lucia Pamela) since the acoustics were quite different on the moon compared to earth…

It is strange, indeed, that we don’t record the sounds on other planets when we land (or pass them by). The public perception is that acoustics is somewhat mysterious (read some of the comments sometime on our Champions of Sound blog, about acoustics in buildings). In the scientific community, though, there is a ton of research going on for underwater acoustics, atmospheric acoustics, etc. The sessions at Acoustical Society of America conferences are dominated by such topics, leaving those of us working on theatre acoustics feeling a bit lonely at times.

It seems, though, that a lot of research for earth-based acoustics is about trying to locate stuff in the sea and air (and, often, how to target it to shoot at it!). The money is there for defense, and there is a very specific goal in mind.

I love sound… and therefore would love to hear other planets. I also love scientific investigation for pure curiousity’s sake. Many others don’t, however, and I’m not sure what the exact reason for listening to other planets would be (come up with one, please!!!).

Someone did come up with a reason to listen to solar flares, though, and even came up with a way for us to listen to them. Check out this post: Staring at the Sun and Listening to it which can even get you to a recording via the BBC website.

– Greg, from Champions of Sound

There was a band where planetary acoustics has been appreciated. Anyone remembers Disaster Area? 42!