In the summer of 2005, a Swiss architecture firm called Instant designed an inflatable addition to the Berlin art space KW.

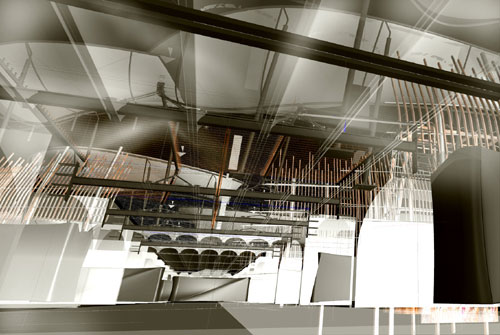

[Image: Courtesy of Instant].

[Image: Courtesy of Instant].

According to I.D.‘s Michael Dumiak, the inflatable, “fiber-reinforced PVC foil” design served as “a temporary summer entrance to the museum’s bamboo garden,” complete with its own staircase and balcony.

The “surprisingly strong, see-through structure,” Dumiak explains, “consist[ed] of inflated stairs leading to an enclosure cantilevered over an 18th-century lane in the formerly communist east.”

It was an internal prosthesis for the building, in other words, a new interior that could be deflated and moved elsewhere.

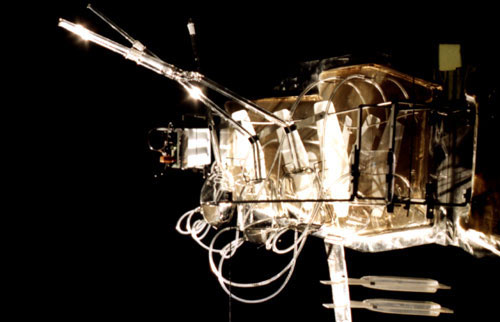

[Image: Courtesy of Instant].

[Image: Courtesy of Instant].

To function properly, and to support the weight of museum visitors, the project used an inflatable variant on structural tensegrity, a concept first developed by sculptor Kenneth Snelson with the input of Buckminster Fuller.

From I.D.: “By attaching two spiral tension cables beneath the weakest part of a strut, and connecting the parts to an air-inflated shell, [Instant’s project engineer Mauro Pedretti] found he could use thin and light – even transparent – materials and still carry heavy loads. One inflatable demo structure supports a light truck.”

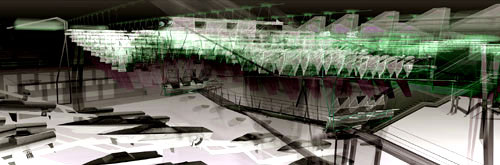

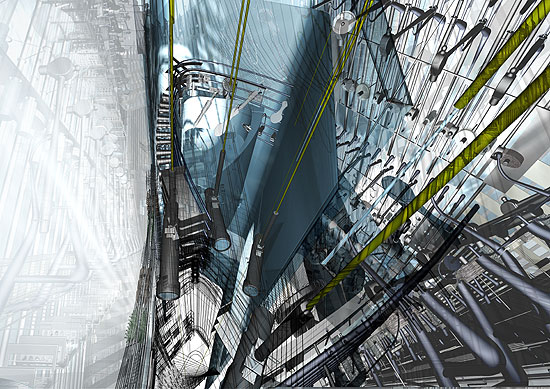

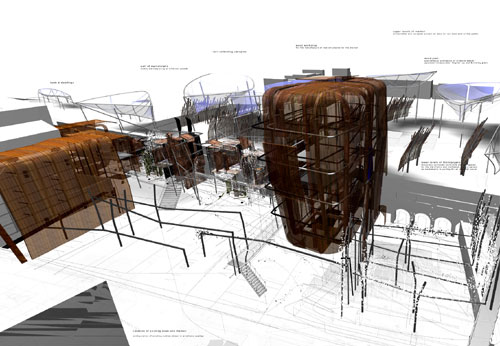

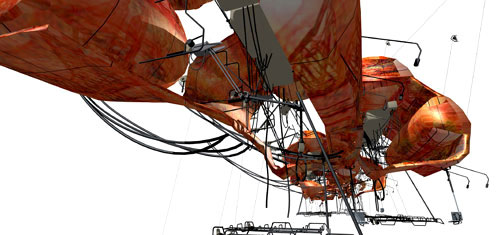

[Image: Two renderings of the project, courtesy of Instant].

[Image: Two renderings of the project, courtesy of Instant].

“Unfortunately,” we read, in Instant‘s own project recap, “the structure was rigid enough to withstand the loads but not its aggressive social urban context. As much as it was successful as a catalyst during the day, it was repeatedly vandalized during the night.”

You can see films of the structure, both real and rendered, on Instant’s website (click on “Detail,” then go to “ON_AIR”).

When I first saw the project, however, flipping through back issues of I.D. last night, I initially misunderstood it as being an entire museum addition, of perhaps indefinite duration – alas, it was a temporary installation, now long gone.

While thus deluded, though, I found myself imagining what might happen if you could design inflatable additions to suburban houses: your in-laws come to visit, or your weird and apparently unemployed uncle who doesn’t really talk to anyone stops by, but there’s literally no room for them inside the house. No worries: the smiling matron of this lucky household pops open some hinges on the back French doors and voilà: the house’s central air-conditioning doubles as an air pump, and you all watch in pleased awe as a twin house, identical in all respects to the one you’re now standing in, takes bloated shape in the lawn behind you. Even your uncle manages to say he’s impressed.

Whole suburbs of inflatable houses!

So I imagined a new chapter for Italo Calvino’s Invisible Cities, in which our untrustworthy narrator is taken out into the gardens of the king – whose courtiers proceed to inflate an entire palace, over a half-dozen acres, full of flamingos and orchids, unrolling in the summer heat. A thousand rooms. Turrets and hallways.

Somewhere in the midst of all that is the chamber you’ll be staying in…

Which reminded me of Tobias Hill’s novel The Cryptographer, in which an ultra-rich Bill Gates-figure purchases literally an entire borough of London, walling it off and transforming it into a private homestead (an agonizingly brilliant set-up for a book, although the story itself falls flat) – at which point I thought: you could inflate an entire borough that has never otherwise existed, sprawling across the marshy floodplains of SE London.

Call it Hackney 2, or Stoke Airington.

It’s one seamless piece of fiber-reinforced PVC foil. It looks like a huge plastic bag lying across the landscape – until the fans kick in. Two days later there’s a whole new city, complete with streets and traffic lights built into the plastic. The lamps have shades, the windows shutters. It’s a Gesamtkunstwerk so total it would make Mies van der Rohe panic.

To pay the investors back, you hire it out as a film set and produce award-winning mobile phone commercials there. Or strangely elaborate pornos, using transparent sets, described as “artistically stunning.”

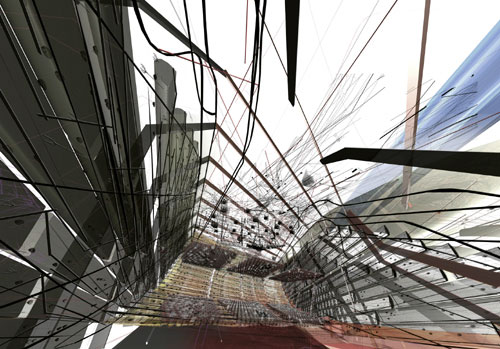

[Image: Courtesy of Instant].

[Image: Courtesy of Instant].

Finally, I came back to Instant and their inflatable design for KW.

What if it had been slimmer and less bulky, for instance, taking up less space inside the museum – and, in a way, more ambitious, with better funding? In other words, what if you could show up at KW with a bunch of air pumps and a different design, and – after clearing the building – you’d inflate a whole new interior, perfectly matched to the architectural plan, subdividing galleries, adding stairways and lofted office space?

You come back a day later and twist a valve, blocking air from entering one room – and so another room unfolds somewhere deeper in the structure. Which, in turn, causes a corridor to inflate, leading onward to another room – where you have a choice: you can either open a valve and inflate the rest of the ground plan, or you can leave the valve closed, and thus a four-story tower of inflated rooms will gradually lift itself above the courtyard…

Leading me to wonder if there’s some Hindu myth, or an obscure Upanishad, in which a multi-lunged god of air parades his wizardry of inflated worlds to stunned worshippers – or if there was a Christian heresy, from medieval Spain, in which the breath of God, a holy spirit animating base flesh, became interpreted as God, Inflationist, Lord of Balloons.

Had the heresy survived, a new breed of cathedrals would now dot the European landscape, supported by inflatable buttresses – inaugurating the Aero-Gothic. Aero-Romanesque. Aero-Baroque.

(To see how easy some of this could really be, take a long stroll through we make money not art‘s inflatable projects archive).

[Image: Merle Prosofsky, Edmonton, Canada; “Backlighting diffused by early-morning fog dramatizes the beginning of the five-hour erection of a 310-tonne vacuum distillation tower. The 37-meter-long, 8.5-m-diameter tower will extract oil for OPTI Nexen’s $3.6-billion Long Lake steam-assisted gravity drainage project from northern Alberta’s oil sands.” Via

[Image: Merle Prosofsky, Edmonton, Canada; “Backlighting diffused by early-morning fog dramatizes the beginning of the five-hour erection of a 310-tonne vacuum distillation tower. The 37-meter-long, 8.5-m-diameter tower will extract oil for OPTI Nexen’s $3.6-billion Long Lake steam-assisted gravity drainage project from northern Alberta’s oil sands.” Via  [Image: Timothy J. Gattie, Boise, ID; “The $330-million Otay River Bridge in Chula Vista, Calif. rises into the morning mist. ‘As the sun peeked through the fog, I couldn’t make out the bridge,’ says Gattie, area engineer for Washington Group. ‘So I put the sun behind the columns, and the picture came out.'” Via

[Image: Timothy J. Gattie, Boise, ID; “The $330-million Otay River Bridge in Chula Vista, Calif. rises into the morning mist. ‘As the sun peeked through the fog, I couldn’t make out the bridge,’ says Gattie, area engineer for Washington Group. ‘So I put the sun behind the columns, and the picture came out.'” Via  [Image: Leah C. Palmer; “The scaffolded ‘village green’ of the recently completed St. Coletta School charter school in Washington, D.C., felt like the belly of the beast to Palmer… Palmer, who studied architecture, is fascinated by the framework of buildings.” Via

[Image: Leah C. Palmer; “The scaffolded ‘village green’ of the recently completed St. Coletta School charter school in Washington, D.C., felt like the belly of the beast to Palmer… Palmer, who studied architecture, is fascinated by the framework of buildings.” Via  [Image: Brian Fulcher, Walnut, CA; “A tunnel construction enthusiast, Fulcher took this shot of workers on the Gotthard Base Tunnel, Sedrun, Switzerland, a Bilfinger Berger-led joint venture. The crew is installing steel support ribs which, with the shotcrete applied to the tunnel’s forward wall, prevent collapse. This portion of the tunnel was bored through ‘squeezing ground, which pushes in on the tunnel walls,’ Fulcher says. ‘It’s very dangerous work.'” Via

[Image: Brian Fulcher, Walnut, CA; “A tunnel construction enthusiast, Fulcher took this shot of workers on the Gotthard Base Tunnel, Sedrun, Switzerland, a Bilfinger Berger-led joint venture. The crew is installing steel support ribs which, with the shotcrete applied to the tunnel’s forward wall, prevent collapse. This portion of the tunnel was bored through ‘squeezing ground, which pushes in on the tunnel walls,’ Fulcher says. ‘It’s very dangerous work.'” Via  [Image: A bunch of pills, via the

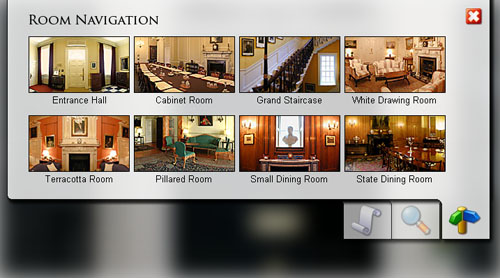

[Image: A bunch of pills, via the  [Image: 10 Downing Street, from the

[Image: 10 Downing Street, from the  [Image: 10 Downing Street, from the

[Image: 10 Downing Street, from the  [Image:

[Image:  [Image: Steve Pike].

[Image: Steve Pike].

[Image: James Foster].

[Image: James Foster]. [Image:

[Image:  [Image:

[Image:  [Image: Annika Schollin].

[Image: Annika Schollin]. [Image: Annika Schollin].

[Image: Annika Schollin].

[Images: Steve Pike’s “vitreous occupational chambers” and “monitor vessel support infrastructure”].

[Images: Steve Pike’s “vitreous occupational chambers” and “monitor vessel support infrastructure”]. [Image: One of Mark Mueckenheim’s urban farms; again, note the insectile nature of student work produced for this unit].

[Image: One of Mark Mueckenheim’s urban farms; again, note the insectile nature of student work produced for this unit].

[Image: Natalia Traverso Caruana’s cultural HQ for Texaco].

[Image: Natalia Traverso Caruana’s cultural HQ for Texaco].

[Images: ©

[Images: © [Image: ©

[Image: © [Image: ©

[Image: © [Image: ©

[Image: © [Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: From

[Image: From

[Images: From

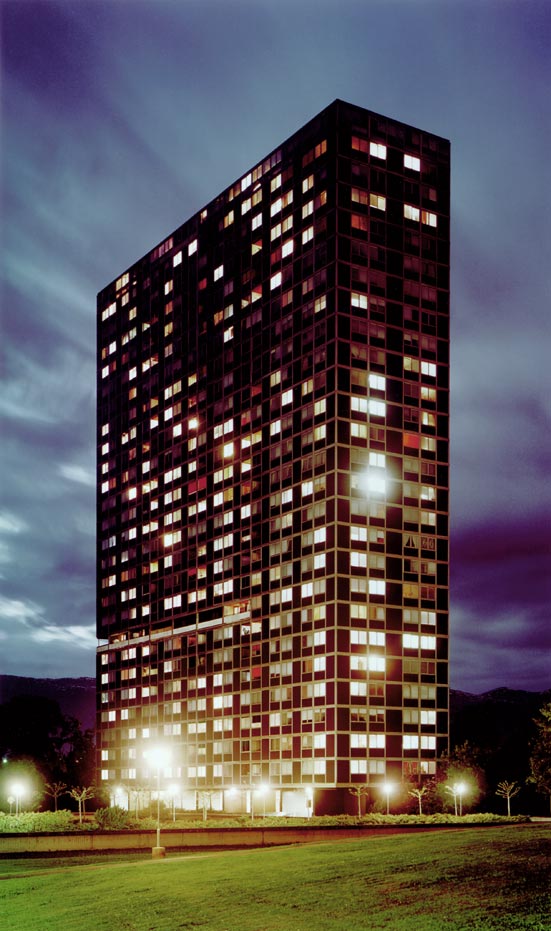

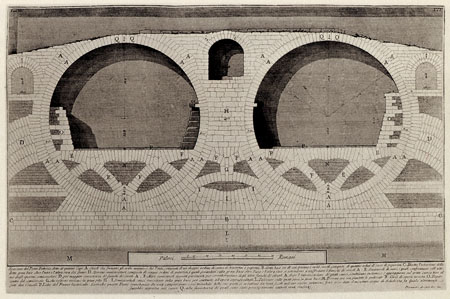

[Images: From  [Image: The interlocking circular network of compound arches beneath Rome’s Quattro Capi Bridge, engraved by

[Image: The interlocking circular network of compound arches beneath Rome’s Quattro Capi Bridge, engraved by  [Image:

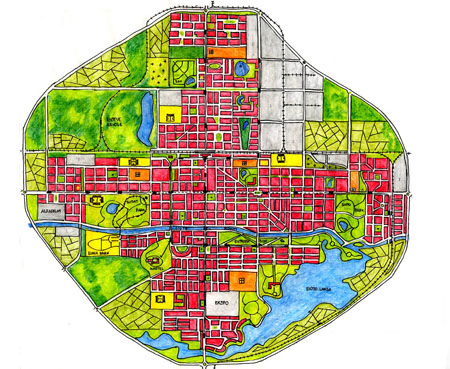

[Image:  [Image: A MetroTram map of

[Image: A MetroTram map of

[Images:

[Images:  [Image: Julian Smith].

[Image: Julian Smith].

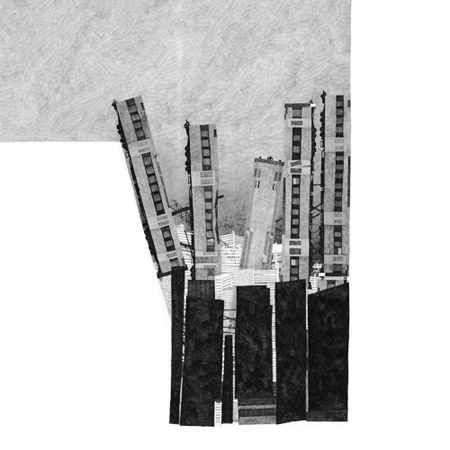

[Images: Carl Douglas].

[Images: Carl Douglas]. [Image: “No architect is credited with the design of the Century Giant Lamp Tower; a local art institute was asked to make a drawing that was then handed off to local experts to produce the renderings.” Courtesy Cui Chaoren/Guzhen Town/

[Image: “No architect is credited with the design of the Century Giant Lamp Tower; a local art institute was asked to make a drawing that was then handed off to local experts to produce the renderings.” Courtesy Cui Chaoren/Guzhen Town/