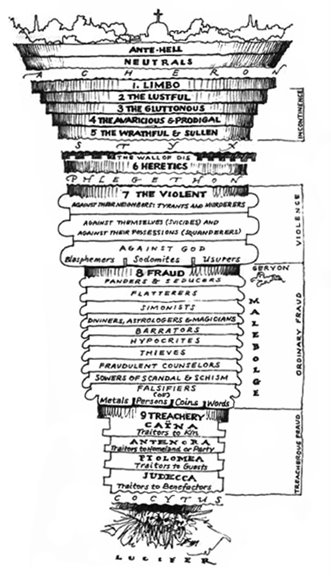

[Image: Dante’s Inferno, as imagined by Barry Moser].

[Image: Dante’s Inferno, as imagined by Barry Moser].

It would seem fitting, on Halloween, to take a quick look at the landscape architecture of Hell—its topography and geographical forms, perhaps even its subsurface geology.

Inspired by a comparison someone made a while back between Edward Burtynsky’s photographs of the Bingham Pit—an open pit copper mine—in Utah, and an illustration by Botticelli of Dante’s Inferno, my interest in Hell’s topography was piqued.

The original comparison:

You’re looking at “Kennecott Copper Mine No. 22, Bingham Valley, Utah” (1983), by Edward Burtynsky, and… Botticelli.

As Adrian Searle describes Botticelli’s work:

Terraced, pinnacled, travelling forever downward, the ledges, cities and basements of hell are furnished with sloughs, gorges and deserts; there are cities, rivers of boiling blood, lagoons of scalding pitch, burning deserts, thorny forests, ditches of shit and frozen subterranean lakes. Every kind of sin, and sinner, is catered for. Here, descending circle by circle, like tourists to Bedlam, came Dante and Virgil. Following them, at least through Dante’s poem, came Botticelli.

The ledges, cities and basements of hell.

But then I found loads of other images, including this skewed and unattributed manuscript scan, showing another mine-like Hell, or Hell as an extraction complex–

—complete with interesting subsurface faults and fractured bedrock, in section. One could easily imagine an obscure branch of the Renaissance academy in Rome publishing tract after tract on the exact geotechnical nature of the Inferno. Is it made of granite? Is it kiln-like? Is it slate? Is it ringed by rivers of uranium tailings?

—complete with interesting subsurface faults and fractured bedrock, in section. One could easily imagine an obscure branch of the Renaissance academy in Rome publishing tract after tract on the exact geotechnical nature of the Inferno. Is it made of granite? Is it kiln-like? Is it slate? Is it ringed by rivers of uranium tailings?

It’s the literary-cosmological subgenre of Hell descriptions.

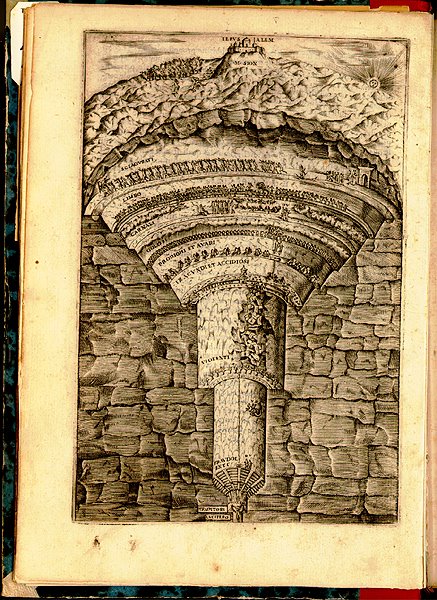

In any case, making a much less explicit visual or even Dantean connection here, there’s also Bartolomeo’s Hell.

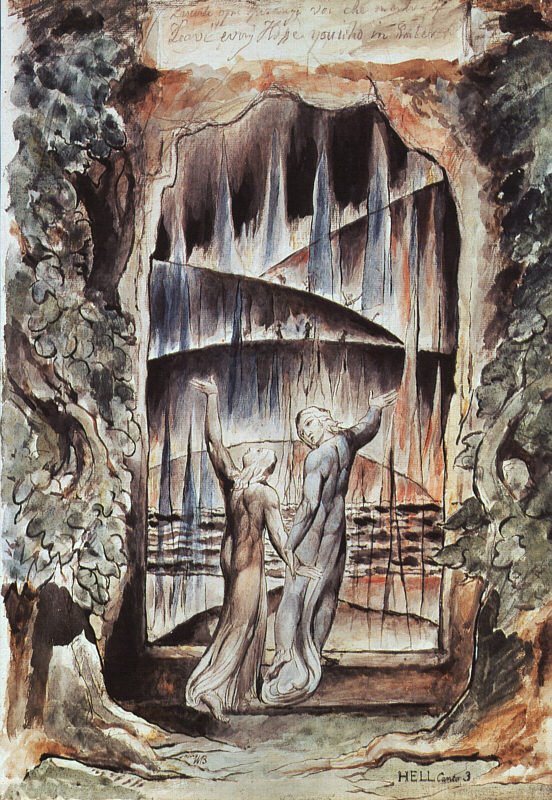

And, finally, making no attempt at all to sustain the visual thread, there’s William Blake–

And, finally, making no attempt at all to sustain the visual thread, there’s William Blake–

—a perennial favorite of mine, which shows us Dante and Virgil both, walking hand-in-hand through a shimmering geomagnetic curtain, a Northern Lights inside the earth. The gates of hell redesigned as a crackling, prehistoric, residual electricity that blasts in vaulted arcs from the faulted walls of granitic stratigraphy, prehuman, technicolor, properly infernal. Hell, as industrially re-designed by Nikola Tesla.

—a perennial favorite of mine, which shows us Dante and Virgil both, walking hand-in-hand through a shimmering geomagnetic curtain, a Northern Lights inside the earth. The gates of hell redesigned as a crackling, prehistoric, residual electricity that blasts in vaulted arcs from the faulted walls of granitic stratigraphy, prehuman, technicolor, properly infernal. Hell, as industrially re-designed by Nikola Tesla.

William Blake meets Jules Verne, who has become a mining engineer and is working on his own translation of Dante. They load-up on blank notebooks and descend together toward the vast, gyroscopic rotations of an electrical hell, taking notes on geology, mapping the stratigraphy of torture machines, where solid rocks mutate and minerals bleed. An epic poem starring geotechnical engineers, and rogue electricians. A hell-mapping expedition.

The climactic scene is a dialogue between Blake and Tesla, who argue, in front of huge glowing domes of black electricity, above vast canals of uranium, that there is an energetic basis for eternal life – or damnation…

Or perhaps the British Museum sends its imperial topographical unit deep into Siberia, where a giant hole has been discovered… Electrical storms form in its overgrown mouth and screams can be heard…

Anyway – Happy Halloween. Don’t forget your hell map.