[Image: From Cool Hand Luke, courtesy of Warner Brothers].

[Image: From Cool Hand Luke, courtesy of Warner Brothers].

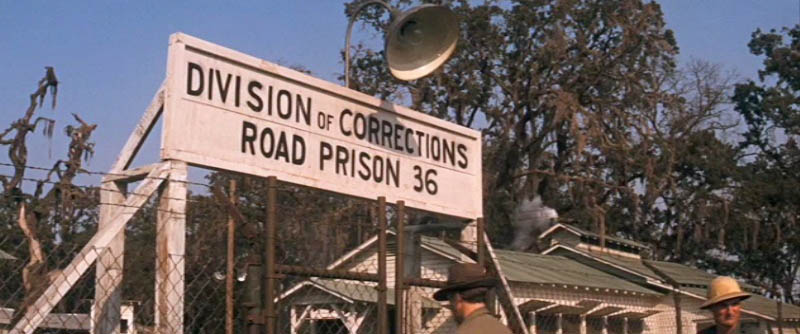

Breaking Out and Breaking In: A Distributed Film Fest of Prison Breaks and Bank Heists—co-sponsored by BLDGBLOG, Filmmaker Magazine, and Studio-X NYC—continued last week with Cool Hand Luke (1967), directed by Stuart Rosenberg.

The film tells the story of Luke Jackson, imprisoned for “maliciously destroying municipal property” by cutting the heads off parking meters. The very first word and image of the film is VIOLATION.

[Image: From Cool Hand Luke, courtesy of Warner Brothers].

[Image: From Cool Hand Luke, courtesy of Warner Brothers].

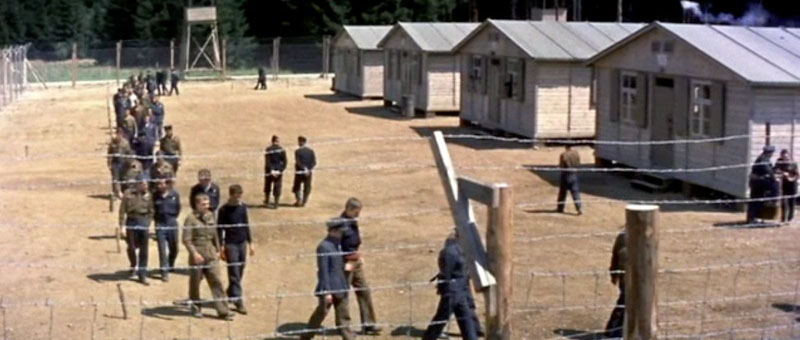

Luke is thus arrested and sent to a work camp in Florida, where he becomes, in effect, part of the country’s emerging national transportation infrastructure, paving rural roads through the Florida swamp.

He is immediately introduced to a new set of limitations. “We got all kinds,” the camp warden announces, referring to the prisoners kept behind fences there in the subtropical heat; but all of them have had to learn how to stay put. To this, the warden adds, “in case you get rabbit in your blood and you decide to take off for home,” you’ll be rewarded with more time in prison and a “set of leg chains to keep you slowed down just a little bit, for your own good. You’ll learn the rules.”

[Image: From Cool Hand Luke, courtesy of Warner Brothers].

[Image: From Cool Hand Luke, courtesy of Warner Brothers].

Later, Luke meets the camp’s “floorwalker,” a man who keeps watch over the prisoners’ boarding house; the floorwalker unloads an absurd and seemingly endless monologue about how the prisoners can avoid spending “a night in the box,” a small building the size of an outhouse with no pretenses of comfort or hygiene. The list of steps by which to avoid this fate—involving everything from laundry to yard tools—is mind-numbing and absolutely impossible to remember.

When the rest of the camp comes back inside to shower and meet these newly arrived state captives, tension between Luke and the existing group’s ostensible leader, nicknamed Dragline, is established immediately. “You don’t listen much—do you, boy?” Dragline growls, mistaking his own corpulence for an ability to intimidate. Luke barely looks at him in return. “I ain’t heard that much worth listening to,” he mutters. “Just a lot of guys laying down a lot of rules and regulations.”

[Image: The camp; from Cool Hand Luke, courtesy of Warner Brothers].

[Image: The camp; from Cool Hand Luke, courtesy of Warner Brothers].

As such, the film offers an interesting mix of, on the one hand, the surreal impossibility of reasoning with the state and its hired representatives (similar, say, to the writings of Franz Kafka); and, on the other, what seems to be a particularly American breed of libertarianism, one in which even parking meters can be interpreted as “just a lot of guys laying down a lot of rules and regulations,” where all instances of authority are meant to be, if not resisted, than at least publicly mocked and undercut.

[Images: Lucas Jackson meets the blinding lights of the state; from Cool Hand Luke, courtesy of Warner Brothers].

[Images: Lucas Jackson meets the blinding lights of the state; from Cool Hand Luke, courtesy of Warner Brothers].

As we’ll see—and this post contains spoilers, for those of you who haven’t seen the film yet—Cool Hand Luke becomes a kind of Trial-like cautionary tale, suggesting that the end result of playfully antagonizing the state can often be repression or death.

[Images: From Cool Hand Luke, courtesy of Warner Brothers].

[Images: From Cool Hand Luke, courtesy of Warner Brothers].

So Luke, a nonviolent offender, is sent off to pave roads in the heat, clearing weeds and snakes, and otherwise maintaining national infrastructure alongside others in his imprisoned crew. They are, in a sense, tragically ensnared in the geographic project of the state, which seeks to expand ceaselessly into underserved rural areas by means of convict-facilitated construction projects. And thus the nation—brutally, physically, literally—is made.

[Images: From Cool Hand Luke, courtesy of Warner Brothers].

[Images: From Cool Hand Luke, courtesy of Warner Brothers].

This relentless growth of the well-policed roadway is perhaps the film’s central motif—even above the film’s admittedly more entertaining scenes, such as Luke living up to his own challenge of eating 50 hard-boiled eggs. For instance, in one scene where a particularly manic Luke successfully challenges the rest of his crew to treat the day’s road-paving assignment like a race, they’re left confused and dumbfounded when the tar truck drives away. The inmates are left staring at a STOP sign. “Where’d the road go?” an exasperated Dragline asks, as if they’re now faced with doing nothing.

But that’s precisely it: the only thing left to do is nothing. This recalls how Luke gets his nickname—”Cool Hand Luke”—by bluffing his way to victory in a poker game, holding a hand “full of nothing.”

In any case, Luke responds by laughing at the idiocy of the entire situation. They ran a race against nothing and no one won.

[Image: From Cool Hand Luke, courtesy of Warner Brothers].

[Image: From Cool Hand Luke, courtesy of Warner Brothers].

For those of you who have seen the film, there is clearly much more in it to discuss that is not spatial or architectural, and I would hope that such a conversation could still take place, either here in the comments or someday with friends; but, given the thematic emphasis of the Breaking Out and Breaking In film series, I’ll focus on just a few more things.

Luke, of course, escapes—three times—but not once, in any long term sense, is he successful, getting hauled back to camp twice in chains.

[Images: From Cool Hand Luke, courtesy of Warner Brothers].

[Images: From Cool Hand Luke, courtesy of Warner Brothers].

Luke’s various punishments for these attempted escapes grow in severity, suggesting a dark answer to the question proposed by a commenter on an earlier BLDGBLOG post: “How do you design a space to break someone’s spirit? A horrible and unimaginable commission.”

Specifically, Luke first spends “a night in the box” and is then forced—inverting all of the power implications associated with digging, tunneling, and moving dirt that we’ve seen so far in the Breaking Out series—to dig and refill a hole in the prison yard, several times over, effectively breaking his will. At one point he is even pushed back into the hole, as if he has, all along, been digging his own grave.

[Images: From Cool Hand Luke, courtesy of Warner Brothers].

[Images: From Cool Hand Luke, courtesy of Warner Brothers].

After witnessing Luke’s very audible collapse, his fellow inmates refuse to speak with him after he stumbles back to the bunkhouse, as if Luke’s aura of indefatigability has been permanently smudged by this performance of desperate weakness. The “horrible and unimaginable commission” of breaking his spirit has, it seems, been accomplished.

However, Luke has one more escape in him, driving off unexpectedly in a road-servicing truck and disappearing into the parched landscape seen reflected in the mirrored sunglasses of the silent “boss” (and sharpshooter) who watches over him.

[Image: From Cool Hand Luke, courtesy of Warner Brothers].

[Image: From Cool Hand Luke, courtesy of Warner Brothers].

This, then, will be my final point about the film: in what is otherwise an obvious—even hackneyed—scene, played for all its poetic and metaphoric power, Luke finds himself alone in an empty church at night, unsure of where to run to next. In many ways, this is where the film’s Kafka-esque themes are most clearly foregrounded, as Luke, addressing God for the second time in the film, finds himself simply speaking to empty rafters.

The church is silent, just a bunch of a wood and darkness, and Luke realizes, once and for all, that no one will be answering.

[Images: From Cool Hand Luke, courtesy of Warner Brothers].

[Images: From Cool Hand Luke, courtesy of Warner Brothers].

Again, this is far from dramatically original, but the scene strongly benefits from its proximity to Luke’s earlier solicitations of authority. In other words, Luke rattles the doors of the divine only to find no response—he finds an empty room and silence. But, when he rattles the doors of the state, an altogether different and more mundane body of authority, it responds by crashing down upon him, relentlessly and absolutely, ultimately leading to his death by sharpshooter (inside the door of a church, no less).

What began as a nonviolent prank, cutting the heads off parking meters, ends, in effect, with a death sentence, as Luke’s ongoing antagonism of the state is seen not as a playful engagement with arbitrary authority, but as an offense so grave—a bluff with an empty hand, holding nothing—that Luke’s very existence is, we might say, reneged or cancelled out. And when he calls up to God, he hears nothing.

[Image: From Cool Hand Luke, courtesy of Warner Brothers].

[Image: From Cool Hand Luke, courtesy of Warner Brothers].

Briefly, I’m reminded of the extraordinary film The Story of Qiu Ju, in which a Chinese villager calls upon the machinations of the state in order to solve a matter of local justice, only to find, to her growing dismay, that she has set into motion something incoherent, lumbering, deaf, and unstoppable.

Only, here, Luke is at the receiving end of something Qiu Ju only witnesses—as if he has snapped the trip-wire of the state, becoming lethally ensnared in a system from which escapes are punishable by death, no matter how trivial the initial offense might be.

[Image: Luke’s apotheosis, ascending above the cross of the roadway; Cool Hand Luke, courtesy of Warner Brothers].

[Image: Luke’s apotheosis, ascending above the cross of the roadway; Cool Hand Luke, courtesy of Warner Brothers].

In any case, Cool Hand Luke is, in the end, a strangely affecting film, seemingly more tragic each time I see it; but I’m sure there’s much more to discuss, so feel free to jump in with any thoughts or comments.

(Up next: Breaking Out and Breaking In continues with Cube. Complete schedule available here).

[Image: The source images for

[Image: The source images for

[Image: A flower by

[Image: A flower by

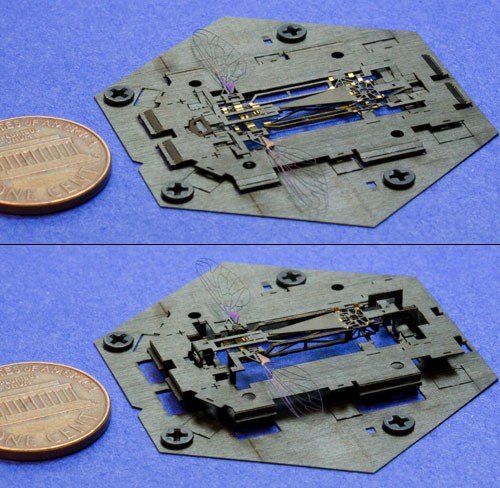

[Image: The pop-up robot sheet, developed at

[Image: The pop-up robot sheet, developed at  [Image: A close-up of the pop-up sheet, courtesy of

[Image: A close-up of the pop-up sheet, courtesy of

[Images:

[Images:  [Image: A 2005

[Image: A 2005

[Image: An otherwise unrelated photo of

[Image: An otherwise unrelated photo of

[Image: Stalag Luft III from

[Image: Stalag Luft III from  [Image: A guard tower from

[Image: A guard tower from

[Images: Establishing the camp; courtesy of

[Images: Establishing the camp; courtesy of

[Images: Looking for weaknesses; courtesy of

[Images: Looking for weaknesses; courtesy of  [Image: Humans disguised as trees; courtesy of

[Image: Humans disguised as trees; courtesy of

[Images: Reading the files of failed escapes; courtesy of

[Images: Reading the files of failed escapes; courtesy of

[Images: The relaxing technique of soiling a garden down your pant legs; courtesy of

[Images: The relaxing technique of soiling a garden down your pant legs; courtesy of  [Image: James Garner looks up with alarm as artificial earthquake waves shudder through the roof; courtesy of

[Image: James Garner looks up with alarm as artificial earthquake waves shudder through the roof; courtesy of

[Images: Steve McQueen as erstwhile

[Images: Steve McQueen as erstwhile

[Images: Measuring the tunnel; courtesy of

[Images: Measuring the tunnel; courtesy of

[Images: Discovering the tunnel with tea; courtesy of

[Images: Discovering the tunnel with tea; courtesy of  [Image: Steve McQueen wants to burrow through the earth like a mole; courtesy of

[Image: Steve McQueen wants to burrow through the earth like a mole; courtesy of  [Image: Steve McQueen’s mole fantasy remains tragically unfulfilled; courtesy of

[Image: Steve McQueen’s mole fantasy remains tragically unfulfilled; courtesy of

[Images: Steve McQueen as topography: the actor’s head emerges from the surface of the earth; courtesy of

[Images: Steve McQueen as topography: the actor’s head emerges from the surface of the earth; courtesy of  [Image: Border games; courtesy of

[Image: Border games; courtesy of

[Images: One of the tunnels; courtesy of

[Images: One of the tunnels; courtesy of

[Image:

[Image:  [Image: A view of the exhibition at

[Image: A view of the exhibition at

[Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: From

[Image: From

[Image:

[Image:  [Image: The manifesto from

[Image: The manifesto from

[Images: Excerpts from David Knight’s “growing database of arcane, marginalized, or forgotten planning practices,” part of

[Images: Excerpts from David Knight’s “growing database of arcane, marginalized, or forgotten planning practices,” part of

[Image: A printer known as the

[Image: A printer known as the  [Image:

[Image: