There is still one more week to invent your own micronation – and win a free copy of the Lonely Planet Guide to Micronations in the process.

There is still one more week to invent your own micronation – and win a free copy of the Lonely Planet Guide to Micronations in the process.

So: in 100 words or less, what, where, how, who, why, when, etc., would your micronation be…? To date, we’ve been approached by a group who “will dig a trench and fill it with ourselves”; we’ve been pitched a “politically autonomous” National Sex Garden; we’ve been introduced to a world of street barricades, built in disused quarters of the world’s cities; we’ve brushed shoulders with the “Sovereign Dictatorship of MOB”; and so on. You don’t actually have to realize your nation, by the way; you can just talk about it. And the more architecturally interesting your idea is, the better.

Illustrations are both acceptable and encouraged.

If you need micronational tips, examples, criteria, etc., see BLDGBLOG’s recent interview with Simon Sellars, one of the Lonely Planet guide’s co-authors – or take a look at Wikipedia’s entry on micronations. Or check out the Helicopter Archipelago.

Then submit to me via email…

The winner – chosen more or less on the whim of BLDGBLOG – will receive a copy of the Lonely Planet Guide to Micronations to read and obsess over, and their idea will appear on BLDGBLOG.

Get cracking!

You have till Friday, December 15th, 2006.

Category: BLDGBLOG

The London Tornadium

There’s been a tornado in NW London: “At least six people were injured and hundreds left homeless when the tornado swept through Kensal Rise at around 11am, tearing the roofs and walls off houses. Eyewitnesses said it lasted for up to 40 seconds; one man said he heard a sound ‘like standing behind a jetliner’.”

It was a “genuine twister.”

[Images: From the Daily Mail].

[Images: From the Daily Mail].

Although tornadoes of this kind are surprisingly frequent in the UK, the event should be taken, The Guardian suggests, as a “warning that such weather events are likely to increase in frequency because of global warming.”

For instance:

In July last year, a tornado in Birmingham damaged 1,000 buildings, causing millions of pounds of damage, while a tornado was reported just off Brighton, on the Sussex coast, this October. A mini tornado swept through the village of Bowstreet in Ceredigion, west Wales, last Tuesday. Terence Meaden, the deputy head of the Tornado and Storm Research Organisation, said the UK has the highest number of reported tornadoes for its land area of any country in the world… He added that the UK was especially susceptible to tornados because of its position on the Atlantic seaboard, where polar air from the north pole meets tropical air from the equator.

In which case, I suggest they build the London Tornadium: an architectural tornado-attractor. Combining urban design; arched viaducts; smooth, valved walls; steel pipes; and complex internal cavitation like a conch shell, the Tornadium will be a kind of urban-architectural sky-trumpet built for the cancellation of storms.

Warm winds and water vapor from the tropics will hit Arctic fronts outside Ireland, then move down toward the city… where the Tornadium, located perfectly at the vertex of converging streets, will suck all storms toward it, defusing their energy (and perhaps acting as a wind-power factory).

Anti-storm architecture. Or pro-storm architecture, for that matter.

What, after all, is the impact of urban design on meteorology?

And could a perfectly engineered great wall of high rises outside the city – each structure a honeycomb of valved passages – prevent all storms from reaching London…?

(See also Aurora Britannica, in which a superstadium full of ring magnets is proposed as a means to trap the Northern Lights in central London).

River Visions of a Midwestern Manhattan

[Image: Floating homes].

[Image: Floating homes].

The reliably excellent Brand Avenue reported last month that “business leaders” in Tulsa, Oklahoma, “are proposing a massive change to that city’s riverfront: a series of new islands covered with public parks and plazas, residential high-rises, and retail arcades, all made possible by the construction of a massive new dam just upstream.”

The project, built upon the alluvial bends of the Arkansas River, will cost nearly $800 million.

[Image: Aerial view of the Channels].

[Image: Aerial view of the Channels].

Referred to as the Tulsa Channels, the scheme is meant “to propel the Tulsa region past its competitors,” stunning them all with unapologetic geotechnical ambition. For instance, the whole thing “begins with an impounding dam at the 23rd street bridge.” This, in turn, “creates a 12.3-mile lake north to Sand Springs.”

At that point:

A 40-acre, man-made island located between the 11th and 23rd street bridges, itself connected by two bridges to the east bank, rises up from the water and anchors the project. The man-made land mass features low- and high-rise residences to the north and south, separated by navigable canals from the public zone.

The whole thing may even help underwrite its own construction costs through the future sale of electricity. Indeed: “Plans call for the project to generate excess energy from hydro, solar and wind power that can be sold back to the power grid for profit.”

It’s not just a suburb, it’s a machine.

[Image: The Tulsa Channels. Two views of a very Manhattan-like model].

[Image: The Tulsa Channels. Two views of a very Manhattan-like model].

Designed by Vancouver-based architects Bing Thom, the Tulsa Channels takes its place alongside another of that firm’s more hydrologically inclined landscape projects: the Trinity River Vision. This is “a master plan for the Trinity River and major tributaries” in Fort Worth, Texas.

[Image: The Trinity River Vision by Bing Thom. The project “will enable up to 10,000 new homes to be constructed in the area (…) once flood protection is in place and levees are removed to open up the land” – as well as once a “new bypass channel and its related dam and isolation gates” have been constructed].

[Image: The Trinity River Vision by Bing Thom. The project “will enable up to 10,000 new homes to be constructed in the area (…) once flood protection is in place and levees are removed to open up the land” – as well as once a “new bypass channel and its related dam and isolation gates” have been constructed].

Brand Avenue – whose original post I’ve more or less repeated, step by step, in its entirety here (sorry!) – points out that these projects bear much in common with yet another riverine plan: this time for a series of manmade islands off the Mississippi coast of St. Louis, as reported by the Forum for Urban Design.

(Note: While you’re reading Brand Avenue, check out their post on the container city).

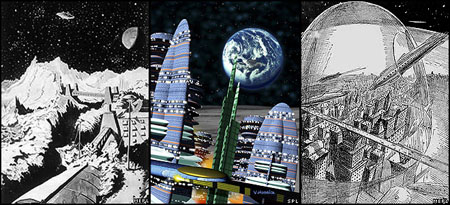

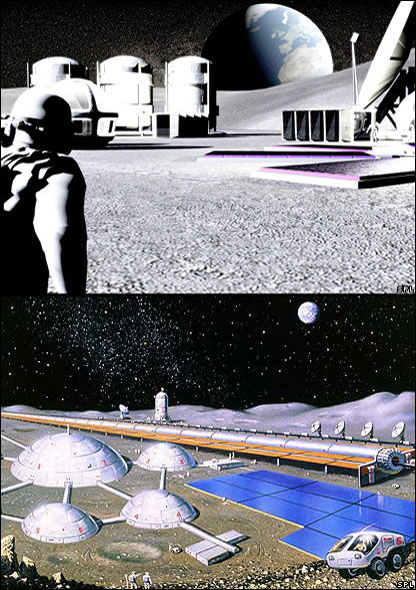

Lunar urbanism 8

Upon relaying today’s news that the United States plans to build a permanent base on the moon, the BBC decided to give us a short, visual history of variously imagined moon bases, as drawn by unnamed artists.

Upon relaying today’s news that the United States plans to build a permanent base on the moon, the BBC decided to give us a short, visual history of variously imagined moon bases, as drawn by unnamed artists.

In the article itself, we learn that NASA thinks “the best approach is to develop a solar-powered moon base and to locate it near one of the poles of the moon – such as the Shackleton Crater near the South Pole.” There, the base “will serve as a science centre and possible stepping stone for manned missions to Mars.” It will also serve as an off-world prison for the – wait –

In the article itself, we learn that NASA thinks “the best approach is to develop a solar-powered moon base and to locate it near one of the poles of the moon – such as the Shackleton Crater near the South Pole.” There, the base “will serve as a science centre and possible stepping stone for manned missions to Mars.” It will also serve as an off-world prison for the – wait –

Of course, a permanent lunar base will have the added benefit of “expand[ing] Earth’s economic sphere” – something the Russians already seem to have realized.

I’m just waiting to see their first postage stamp. And their flag. And the first moon-born baby – who will grow up to lead a death cult in the deserts of western China. And then the first moon war…

Before the big day when BLDGBLOG wins a three-month residency for lunacy in architectural research…

(See also Lunar urbanism 7 and so on).

Bamiyan erasure

[Image: Simon Norfolk. “Victory arch built by the Northern Alliance at the entrance to a local commander’s HQ in Bamiyan. The empty niche housed the smaller of the two Buddhas, destroyed by the Taliban in 2001.” From Afghanistan: Chronotopia.]

[Image: Simon Norfolk. “Victory arch built by the Northern Alliance at the entrance to a local commander’s HQ in Bamiyan. The empty niche housed the smaller of the two Buddhas, destroyed by the Taliban in 2001.” From Afghanistan: Chronotopia.]

Just a quick note to say that I’ve added two images to last week’s interview with Simon Norfolk – which you should definitely read if you get a chance (it’s very long). The new images include this photograph, above, which centers on one of the destroyed Buddhas of Bamiyan.

(Thanks, Simon!)

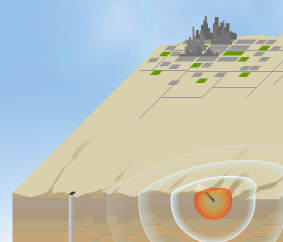

Terrestrial weaponization

[Image: From a simulation of nuclear bunker buster technology, produced by the Union of Concerned Scientists].

[Image: From a simulation of nuclear bunker buster technology, produced by the Union of Concerned Scientists].

Defense Tech introduces us to the “earthquake array,” a “focused underground shockwave that amounts to an artificial earthquake.” This “artificial earthquake” will be put to use by the Air Force, of all people (not the Earth Force?), in order to annihilate underground targets.

Intriguingly, the shockwave will cause all regional tunnels, bunkers, mines, sewers, nightclubs, basement TV rooms, commercial show caves, etc., to collapse – which means that the bomb is actually a kind of landscape weapon, de-caving the earth from within.

“The secret,” we read, “is in effectively combining 20 separate explosions into a coherent pulse.”

More interesting than explosives, however, would be the phenomenal amount of patience and long-term thinking required to execute a slightly different plan: seeing that the future rise of a distant empire is all but historically inevitable, you and a crack team of undercover geotechnical engineers go deep into what will soon be enemy territory – even if not for another 500 years – and you install several hundred acres of massive vibrating plates a thousand feet below ground. You hook them up to something – perhaps a geothermal well – and then you landscape the hell out of the place.

No one will know you were there.

Then 500 years goes by, at which point that distant empire is now your biggest rival – and that means your moment has come. Your weapon is ready. You activate the earth-plates.

Within seconds, a shuddering manmade tectonic groan of undeclared, anti-architectural, vibrational warfare levels their whole civilization. Your plan works.

It’s the earthquake array, as it really should be. Terrestrial weaponization. Earth War I.

(For quite similar thoughts, involving James Bond, see BLDGBLOG’s guide to tectonic warfare).

Science Fiction and the City

In case you missed, or miss, BLDGBLOG’s earlier interview with novelist Jeff VanderMeer, you can now read it in print…

The full interview – complete, I believe, with artist John Coulthart‘s excellent bookplates – was just published in the new issue of 032c, an arts/culture/politics magazine produced in the groundless, post-historical urban spaceship of Berlin.

The full interview – complete, I believe, with artist John Coulthart‘s excellent bookplates – was just published in the new issue of 032c, an arts/culture/politics magazine produced in the groundless, post-historical urban spaceship of Berlin.

The theme of the issue is “Life in the Long Shadow of War” – which, judging from the cover, appears to have something to do with European women suggestively eating peeled fruit… Other contributors include Thomas Pynchon, Hans Ulrich Obrist, and Rem Koolhaas.

So what does Mr. VanderMeer have to say in this interview? An excerpt:

So what does Mr. VanderMeer have to say in this interview? An excerpt:

As a novelist who is uninterested in replicating “reality” but who is interested in plausibility and verisimilitude, I look for the organizing principles of real cities and for the kinds of bizarre juxtapositions that occur within them. Then I take what I need to be consistent with whatever fantastical city I’m creating. For example, there is a layering effect in many great cities. You don’t just see one style or period of architecture. You might also see planning in one section of a city and utter chaos in another. The lesson behind seeing a modern skyscraper next to a 17th-century cathedral is one that many fabulists do not internalize and, as a result, their settings are too homogenous.

Of course, that kind of layering will work for some readers – and other readers will want continuity. Even if they live in a place like that – a baroque, layered, very busy, confused place – even if, say, they’re holding the novel as they walk down the street in London [laughter] – they just don’t get it. So you have to be careful how you do that.

And if you happen to be in Moscow, there will be an invitation-only party for the magazine’s release on December 7th; and, in Beijing, another such party will be held on December 12th.

If you want an invitation, I assume you just email 032c.

Angles of entrance

[Image: Geoffrey George takes us on a stroll through Detroit’s Michigan Central Station, a building both abandoned and unfinished, in this Flickr set; the above image, so wonderfully skewed and angular, is the strongest of the lot – in fact, it’s rather hard to stop looking at].

[Image: Geoffrey George takes us on a stroll through Detroit’s Michigan Central Station, a building both abandoned and unfinished, in this Flickr set; the above image, so wonderfully skewed and angular, is the strongest of the lot – in fact, it’s rather hard to stop looking at].

Wreck-diving London

[Image: From Blend; those aren’t typos, by the way – it’s Dutch].

[Image: From Blend; those aren’t typos, by the way – it’s Dutch].

Little Venice is a small riverine village east of Notting Hill on the manmade canals of Victorian London. Its waterways were all designed in the early 1800s by Isambard Kingdom Brunel, the same engineer behind the machinery that excavated London’s first Tube tunnels.

Now, however, the Romantic canals and artificial rivers of Little Venice offer something of an unintended glimpse, or working model, of the London yet to come.

“Tide levels are steadily increasing owing to a combination of factors,” the UK’s Environment Agency warns. “These [factors] include higher mean sea levels, greater storminess, increasing tide amplitude, the tilting of the British Isles (with the south eastern corner tipping downwards) and the settlement of London on its bed of clay.”

Post-glacial rebound is the technical term for this “tilting of the British Isles.” That tilt comes as northern Scotland’s deglaciated mountain valleys rise steadily upward, decompressing from the weight of lost ice caps. Like a geologically-themed, slow-motion amusement park ride, the British Isles are thus “tilting,” with Scotland’s rebound pushing London into the sea.

Climate change only adds to the city’s worries.

[Image: London, flooding; via the Environment Agency – if you’re a Londoner, type in your postcode and see if you’re at risk from water…].

[Image: London, flooding; via the Environment Agency – if you’re a Londoner, type in your postcode and see if you’re at risk from water…].

Short of capping the Highlands in new glaciers of lead, however, or attaching gigantic hot air balloons to the spires of churches to pull the city skyward, London will eventually flood: its undersea fate is geologically inevitable. Whether this occurs in a hundred years or a hundred centuries, London will become a city of canals – before it is lost to the sea entirely. It is a new Atlantis, sinking deeper each day into the oceanic embrace of hydrology.

Yet is worrying about this fate the appropriate response? Perhaps such an outcome isn’t tragic at all. Perhaps, if we view this future with a certain architectural curiosity, we can respond with something like enthusiasm.

In which case: what future city will we see upon the Thames?

In the estuarial distance, perhaps a thousand new artificially intelligent Thames Barriers will lift and fold their bulwarked walls against the onslaught of the sea. Moving levees, crawling and motorized – a kind of hydrological Maginot Line – insect-like and powered by tides, will encircle the British archipelago. We’ll drive across inland lagoons on floating motorways.

House-boats and cargo ships will anchor ten meters above the pavements of Trafalgar, unloading passengers and cargo, Admiral Nelson now wreathed in seaweed. Adventure tourism firms will lead scuba diving expeditions through the reefs of Westminster, wealthy clients spear-fishing eels in the back rooms of flooded estate agents.

[Image: J.M.W. Turner].

[Image: J.M.W. Turner].

London’s underwater fate thus presents us with at least two intriguing lines of speculation. On the one hand you’ve got possible next steps for Greater London’s imperial flood control regime; on the other, a vision of evacuation, collapse and abandonment after the city’s oceanic war has been lost. Either way, the future of London is with the sea.

It’s easy to imagine, in fact, that the entire English coastline might soon be buttressed behind 40-meter high locks and channels. Thames Water, already struggling to keep the Tube dry from river overflow, would need its own nuclear power plants, droning into the 27th century, just to fuel its complex networks of pumps and aquatic regulators. New canals, distributing North Sea storm surges up toward marshland desalination plants, could store that water in huge inland seas, well-protected reservoirs processed for drinking. A new Lake District, militarized, utopian, walled with concrete, might be visited by future Wordsworths, Coleridge and his ancient mariner setting sail up the Thames, now freshly dredged as far as Edinburgh.

But once those defenses fail, and London tilts further beneath the waves?

[Image: J.M.W. Turner].

[Image: J.M.W. Turner].

The London Underground will be lost immediately, transformed into something between sewer and urban aquarium. Cellars and the steps that lead to them will make London a city of valves, pulsing from below with subsurface waters that burst up and outward from the windows of buildings, all of London a simulacrum of Versailles – an unintended architecture of choreographed fountains – showing off in arcs sprayed upon the facades of abandoned shopping malls.

Perhaps no one will be around to witness all this: cold water will lap across the bleached dome of St. Paul’s unseen, for centuries…

Till, someday, a distant heir of J.M.W. Turner will return sunburnt from the tropics to find London an archipelago of failed sea walls and water-logged high-rises, the suburbs an intricate filigree of uninhabited canals, bonded warehousing forming atolls amidst sandbanks and deltas. Amidst new islands of former rooftops, he will rename the constellations to fit British geography as it used to be: Piccadilly Circus, King’s Cross, Tottenham Court Road, all burning above a city that quietly rushes with black waves.

Perhaps there will even be a star named after Little Venice, as its namesake rebounds further and further beneath the sea.

(Note: A slightly different version of this article, translated into Dutch, was published several months ago in Blend magazine – for whom I continue to write monthly columns, in case you’re in Holland and you need something to read… And if you’re as dizzyingly in love with J.M.W. Turner as I am, consider reading Peter Ackroyd’s brief biography of him this winter).

Automotive Ossuary

Brazilian artist Alexandre Orion turned a São Paulo transport tunnel into a kind of graphic charnel house, lined with skulls.

Brazilian artist Alexandre Orion turned a São Paulo transport tunnel into a kind of graphic charnel house, lined with skulls.

He created the images, the project’s website explains, “by selectively scraping off layers of black soot deposited on those walls in the short life of this orifice of modernity.”

And what a lovely orifice it is…

Specifically, Orion scraped, cleaned, and rubbed down through soot “until reaching the natural color of the walls” – inevitably leading me to wonder what other worlds, of figures and images and narrative sequences, might exist in some future graphic tense beneath layers of urban pollution…? And could one prepare for the accumulation of soot by attaching stencils to the walls of tunnels – only to remove those in five years, revealing imagery?

Specifically, Orion scraped, cleaned, and rubbed down through soot “until reaching the natural color of the walls” – inevitably leading me to wonder what other worlds, of figures and images and narrative sequences, might exist in some future graphic tense beneath layers of urban pollution…? And could one prepare for the accumulation of soot by attaching stencils to the walls of tunnels – only to remove those in five years, revealing imagery?

Interestingly, the rough geological equivalent of this procedure can be found throughout the American Southwest, in the form of various “newspaper rocks“

– where layers of desert varnish have been scraped away to reveal natural rock pigmentation, thus allowing the production of representational art.

In any case, the descriptive text on Orion’s website seems to go downhill fairly quickly – we’re soon scraping soot off the walls of repression and peeling away consciousness itself, and we’re meant to be very, very angry while doing so – but the funny thing is, because voluntarily scrubbing sections of a public underpass isn’t actually illegal in São Paulo – and would seem, in fact, to be a sign of refined citizenship – try as they might, Brazil’s patient and well-organized police force couldn’t charge Orion with anything.

In any case, the descriptive text on Orion’s website seems to go downhill fairly quickly – we’re soon scraping soot off the walls of repression and peeling away consciousness itself, and we’re meant to be very, very angry while doing so – but the funny thing is, because voluntarily scrubbing sections of a public underpass isn’t actually illegal in São Paulo – and would seem, in fact, to be a sign of refined citizenship – try as they might, Brazil’s patient and well-organized police force couldn’t charge Orion with anything.

Instead, the fire crews showed up and washed it down with hoses.

Instead, the fire crews showed up and washed it down with hoses.

(Via Paul Schmelzer’s Eyeteeth, which quotes a nice recap of Orion’s project).

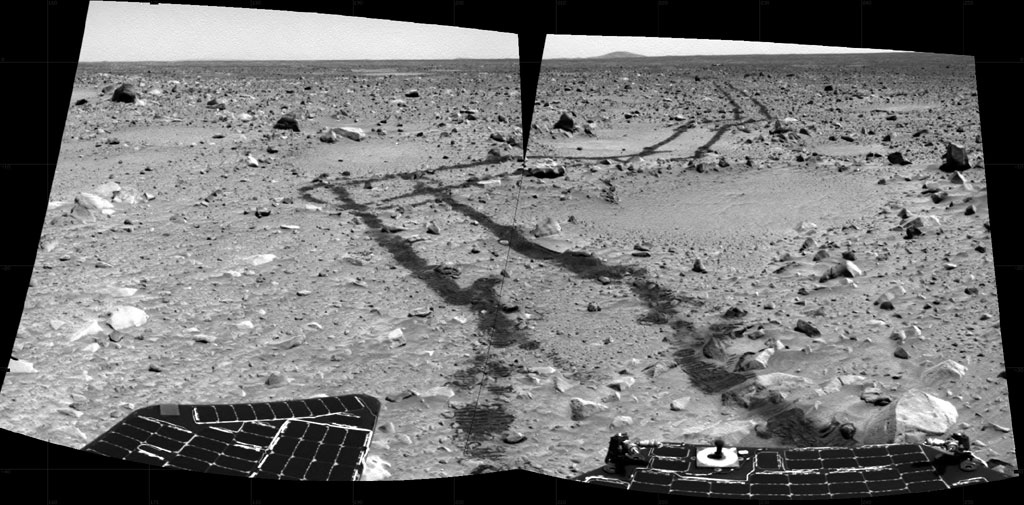

Snowdonia

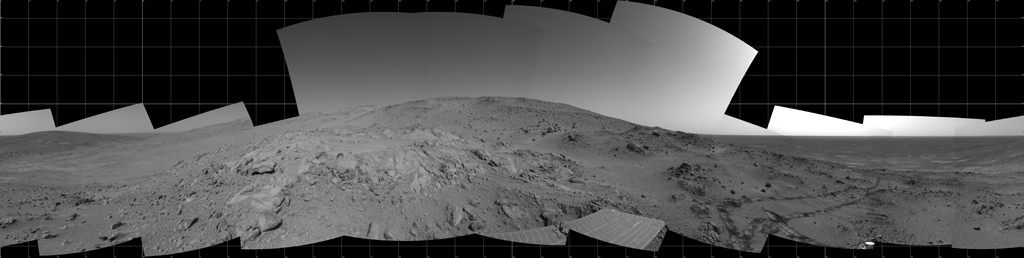

One of the things I’ve always found most interesting about photographs from Mars isn’t the planet itself – its landscapes and geology – but the strange visual style associated with the images: spliced together from multiple stills, the edges of the photos break up into black rectangular voids, as if the scene has been consumed by Russian Suprematism, the revenge of art history coming back to us from offworld sources.

One of the things I’ve always found most interesting about photographs from Mars isn’t the planet itself – its landscapes and geology – but the strange visual style associated with the images: spliced together from multiple stills, the edges of the photos break up into black rectangular voids, as if the scene has been consumed by Russian Suprematism, the revenge of art history coming back to us from offworld sources.

Malevich as landscape photographer.

So I was pleasantly surprised to see the same approach used to the same effect, whether intentional or not, in these photos of Mt. Snowdon, Wales, taken by Flickr user Stuey G.

So I was pleasantly surprised to see the same approach used to the same effect, whether intentional or not, in these photos of Mt. Snowdon, Wales, taken by Flickr user Stuey G.

In other words, because of the culturally recent Martian resonance of spliced photography, these scenes from the earth appear unearthly; the topography – for me, at least – seems strangely removed from terrestrial expectations.

In other words, because of the culturally recent Martian resonance of spliced photography, these scenes from the earth appear unearthly; the topography – for me, at least – seems strangely removed from terrestrial expectations.

This isn’t Wales, the style implies, but some new terrain altogether, geologically other.

Or not, of course, in which case you just think these look like photos of Mt. Snowdon; but take several hundred more of these things, write some text – and soon you’ve got a new planetary narrative: discovering other worlds, right here on earth beside us.

Or not, of course, in which case you just think these look like photos of Mt. Snowdon; but take several hundred more of these things, write some text – and soon you’ve got a new planetary narrative: discovering other worlds, right here on earth beside us.

(For more Mars photos, see NASA; for more Snowdon photos, see Stuey’s Snowdonia page. On an unrelated note, Mr. G. understandably loves his new ground-radar machine).