A recent landscape design competition sought to rethink the Vatnsmýri airport grounds in Reykjavík, Iceland, putting those old runways to use, for instance, as new urban park space. The entries to the competition are quite interesting, in fact, so I’ve posted some of them, below, focusing on one particular project at the end of this post (so please scroll down if you’ve already read about this competition).

First, then, here’s the old Vatnsmýri airport and its earthen geometry of intersecting runways. This is the site – star-like and stretching out to its surrounding landscapes – within which the designers had to work.

[Images: The Vatnsmýri airport grounds, Reykjavík, Iceland. Photos courtesy of the Reykjavík City Planning Committee].

[Images: The Vatnsmýri airport grounds, Reykjavík, Iceland. Photos courtesy of the Reykjavík City Planning Committee].

And here are some of the project entries, which I have posted in order, from shortlisted entries through to the big prize winners – but I have selected them on the purely superficial criterion of my own visual interest. Some of these projects, including two grand prize winners, are, I’m sure, absolutely fascinating, but small JPGs of their proposals simply don’t give you very much to work with.

So, with genuine apologies to those designers whose work does not appear here, take a look at some of the entries.

[Image: By Alexander D’Hooghe, et al.].

[Image: By Alexander D’Hooghe, et al.].

[Image: By Antonello Boatti, Birgir Breiðdal, and Nicola Ferrara].

[Image: By Antonello Boatti, Birgir Breiðdal, and Nicola Ferrara].

[Image: By Lola E. Sheppard and Mason White].

[Image: By Lola E. Sheppard and Mason White].

[Image: By Rolf J. Teloh, et al.].

[Image: By Rolf J. Teloh, et al.].

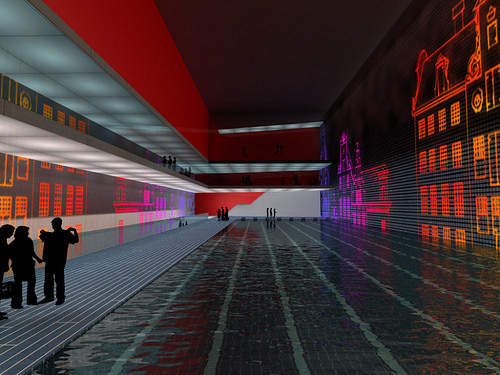

[Image: By Thomas Forget and Jonathan F. Bell].

[Image: By Thomas Forget and Jonathan F. Bell].

[Image: By Andrés Perea Ortega, et al.].

[Image: By Andrés Perea Ortega, et al.].

[Image: By Beatriz Ramo, et al.].

[Image: By Beatriz Ramo, et al.].

[Image: By Peer T. Jeppesen, et al.].

[Image: By Peer T. Jeppesen, et al.].

[Image: By Belinda Kerry, Andrew Lee, Fiona Harrisson, and Blake F. Bowers].

[Image: By Belinda Kerry, Andrew Lee, Fiona Harrisson, and Blake F. Bowers].

[Image: By Manuel Lodi, et al.].

[Image: By Manuel Lodi, et al.].

[Image: By Jeff Turko, Guðjón Þór Erlendsson, Dagmar Sirch, and Sibyl Trigg].

[Image: By Jeff Turko, Guðjón Þór Erlendsson, Dagmar Sirch, and Sibyl Trigg].

[Image: By Graeme Massie, Stuart Dickson, Alan Keane, and Tim Ingleby].

[Image: By Graeme Massie, Stuart Dickson, Alan Keane, and Tim Ingleby].

And now I want to zero-in on one of the projects.

Here, then, is a quick exploration of a shortlisted entry by Lola E. Sheppard and Mason White of the Toronto-based firm Lateral Architecture.

[Image: By Lola E. Sheppard and Mason White].

[Image: By Lola E. Sheppard and Mason White].

Their project begins, we read, “by establishing ‘no-build’ zones or public landscapes. The figure of the runway is used to identify three primary axes. Each former runway is converted into a ‘greenway’ that uses a quality of the city as its primary trait.”

[Images: By Lola E. Sheppard and Mason White].

[Images: By Lola E. Sheppard and Mason White].

The greenways are then given new programs, or functions, which the architects define as Ecology, Recreation, and Production.

The Ecology greenway, for instance, “is conceived of as a dot-matrix of cellular ecosystems, organic rooms, landscape surfaces of hard and softscape, gardens and pools.”

[Images: By Lola E. Sheppard and Mason White].

[Images: By Lola E. Sheppard and Mason White].

The Production greenway, which I like quite a lot, has been “treated as a barcode of interdependent production activities, with changing densities of fish farming, greenhouses for fruit, vegetable and flower production, allotment gardens, markets and tree farming.”

Fish Farms are located on the western end of the strip and serve both a local populace through an adjacent market and an international market with a distribution port. A series of greenhouses line the edges of the existing runway and create cluster of outdoor ‘rooms.’ Interspersed are modest community garden and farm plots which subdivide the space and integrate the adjacent communities into the strip. A second market, proposed at the triangle intersection, serves to sell these vegetables and flowers to the Reykjavik community. A dense forest continues the barcode and creates wood for the initial construction phases. This forest gains more permanence in successive phases and is used to absorb carbon dioxide and offer oxygen to the new development.

All of which sounds great to me. There is even a “network of geothermal pipes” that does something or other for the fish farms.

But how spectacular to live in a city full of greenhouses! Re-formatting architectural interiors to grow fruit. You wander around at night through certain districts of your city watching strange plants grow behind glass. The air smells alive. It’s quiet.

And there are fewer cars – because entire streets have been blocked off and replaced with greenhouses, freeing up former parking lots to become orchards and small croplands. Microfarms. Perhaps new coastal rivers even cut through the city, engineered by heroic valves tucked away beneath the streets, irrigating various neighborhoods and responding to lunar tides.

What used to be highway flyovers are now orange groves, and over there, in the abandoned airport, fields of medicinal flowers now grow.

[Image: By Lola E. Sheppard and Mason White].

[Image: By Lola E. Sheppard and Mason White].

On a vaguely related note, meanwhile, my own description here has reminded me of the discovery last winter that listening to birdsong might actually improve mental health. So imagine ten thousand new birds up in the trees of this greenhouse city as the sun begins to rise over huge warehouses walled with angled glass panes, like something out of analytical Cubism, and you’re just sitting there eating toast with local honey, listening to morning birdsong, surrounded by plants.

[Image: By Lola E. Sheppard and Mason White].

[Image: By Lola E. Sheppard and Mason White].

In any case, the final greenway proposed by this project would be a “recreation corridor” in which “spaces for formal and informal activities” will be built, including “soccer fields, running tracks, basketball, tennis and volleyball, local schools and playgrounds.”

[Image: By Lola E. Sheppard and Mason White].

[Image: By Lola E. Sheppard and Mason White].

The greenways will all knit together and criss-cross, following the buried logic of the old runways.

In ten years’ time, you can take your kids out into the middle of a forest and say: “They used to land planes here…”

(All of these images are also available in a small Flickr set).

The structural engineers over at

The structural engineers over at  [Image: A submission to London’s recent

[Image: A submission to London’s recent  [Image: 3d-printing new deltas into existence, courtesy of

[Image: 3d-printing new deltas into existence, courtesy of  [Image: Courtesy of the

[Image: Courtesy of the  [Image: Photo by

[Image: Photo by

[Images: By

[Images: By  [Image: Photo by Ben Nilsson of Big Ben Productions].

[Image: Photo by Ben Nilsson of Big Ben Productions]. [Images: All photos by Ben Nilsson of Big Ben Productions].

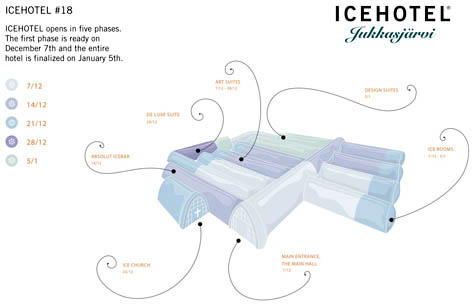

[Images: All photos by Ben Nilsson of Big Ben Productions]. So how is the ICEHOTEL actually built?

So how is the ICEHOTEL actually built?  [Image: Photo by Ben Nilsson of Big Ben Productions].

[Image: Photo by Ben Nilsson of Big Ben Productions]. [Image: By Ben Nilsson of Big Ben Productions].

[Image: By Ben Nilsson of Big Ben Productions]. [Image: A cargo elevator beautifully shot by

[Image: A cargo elevator beautifully shot by  [Image:

[Image:

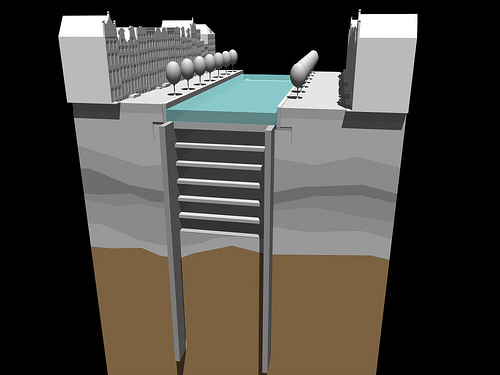

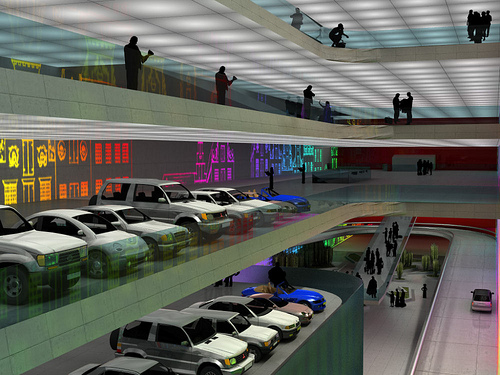

[Image: A new underground city for Amsterdam, by

[Image: A new underground city for Amsterdam, by  [Image: Underground Amsterdam by

[Image: Underground Amsterdam by

[Images:

[Images:  [Image:

[Image:  I’ve got a new post up on io9 this morning: the

I’ve got a new post up on io9 this morning: the  [Image: By Jeffrey Inaba/

[Image: By Jeffrey Inaba/ [Image: By Jeffrey Inaba/

[Image: By Jeffrey Inaba/ [Image: By Jeffrey Inaba/

[Image: By Jeffrey Inaba/

[Images: By Jeffrey Inaba/

[Images: By Jeffrey Inaba/

[Image: From the series

[Image: From the series

[Images: From the series

[Images: From the series  [Image: From the series

[Image: From the series  [Image: From the series

[Image: From the series

[Images: From the series

[Images: From the series  [Image: From the series

[Image: From the series  [Images: From the series

[Images: From the series  [Image: From the series

[Image: From the series