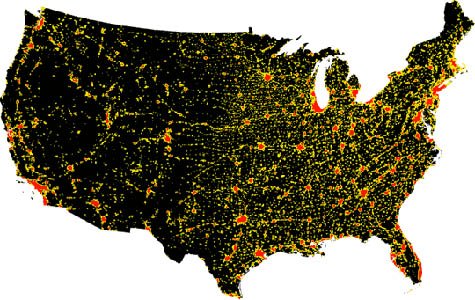

[Image: The population density of the United States, ca. 2000, via Wikipedia].

[Image: The population density of the United States, ca. 2000, via Wikipedia].

If you’ll excuse a quick bit of landscape-inspired political speculation, I was reminded this morning of something I read last year on Boing Boing and which has stuck with me ever since – and that’s that there are more World of Warcraft players in the United States today than there are farmers.

Farmers, however, as Boing Boing and the original blog post it links to are both quick to point out, are often portrayed in media polls as a voice of cultural and political authenticity in the United States. They are real Americans, the idea goes, a kind of quiet majority in the background that presidential candidates and media pundits would be foolish to overlook.

If you want a real cross-section of Americana, then, you’re supposed to interview farmers and even hockey moms – but why not World of Warcraft players? This is just a rhetorical question – it would be absurd to suggest that World of Warcraft players (or architecture bloggers) somehow have a special insight on national governance – but, as cultural demographics go, it’s worth asking why politicians and the media continue to over-prioritize the rural and small-town experience.

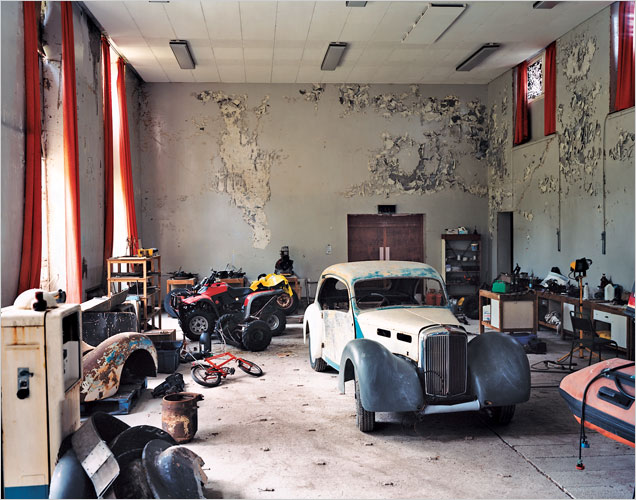

[Image: A street in Columbus, Wisconsin, the small and, at the time, semi-rural town in which I grew up, photographed under a Creative Commons license by Royal Broil].

[Image: A street in Columbus, Wisconsin, the small and, at the time, semi-rural town in which I grew up, photographed under a Creative Commons license by Royal Broil].

In a related vein, it’s often said in the U.S. that certain politicians simply “don’t understand the West”: they’re so caught up in their big city, coastal ways that they just don’t get – they can’t even comprehend – how a rancher might react to something like increased federal control over water rights or how a small-town mayor might object to interfering rulings by the Supreme Court. Politicians who don’t understand the west – who don’t understand the rugged individuality of ranch life or the no-excuses self-responsibility of American small towns – are thus unfit to lead this society.

But surely the more accurate lesson to be drawn from such a statement is exactly the opposite?

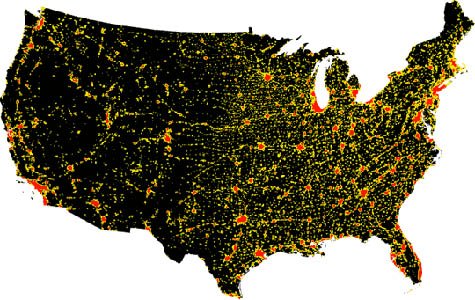

One could even speculate here that politicians from small towns, and from the big rural states of the west, have no idea how cities – which now house the overwhelming majority of the American population – actually operate, on infrastructural, economic, socio-political, and even public health levels, and so they would be alarmingly out of place in the national government of an urbanized country like the United States.

If the United States – if the entire world – is rapidly urbanizing, then it would seem like literally the last thing we need in the White House, in an era of collapsing bridges and levees, is someone whose idea of public infrastructure is a dirt road.

Put another way, perhaps coming from a ranch or a small town is precisely why a certain candidate might be unable to govern a nation that is now 80% urban.

It’s a political collision of landscape management strategies.

[Image: Urban areas in the U.S. Map courtesy of NASA].

[Image: Urban areas in the U.S. Map courtesy of NASA].

On the other hand, perhaps this juxtaposition would be exactly why a rural or small-town candidate could be perfect for the job – fresh perspectives, thinking outside the box, and so on. After all, a good rancher is surely a better leader than a failed mayor.

Or, to take an even more aggressive stand against this argument, surely the administrative specifics of your previous professional life – you were a doctor, a minister, a novelist, a governor, a business owner, a soccer dad – are less important than your maturity, knowledge, clarity of thought, and judgment?

Even having said that, though, I can’t help but wonder if a candidate might “understand” one particular type of settled landscape – a small town, a thinly populated prairie, an icy state with a population one-fifth that of Chicago – but not another, more heavily urbanized type of landscape (i.e. the United States as a whole).

So I was reminded again of the opening statistic from Boing Boing – a statistic that I have not researched independently, mind you, but that appears to be based on this data – when I read that President Bush had stopped off this morning to speak about the credit crisis “with consumers and business people at Olmos Pharmacy, an old-fashioned soda shop and lunch counter” in San Antonio, Texas.

The idea here – the spatial implication – is that Bush has somehow stopped off in a landscape of down-home American democracy. This is everyday life, we’re meant to believe – a geographic stand-in for the true heart and center of the United States.

But it increasingly feels to me that presidential politics now deliberately take place in a landscape that the modern world has left behind. It’s a landscape of nostalgia, the golden age in landscape form: Joe Biden visits Pam’s Pancakes outside Pittsburgh, Bush visits a soda shop, Sarah Palin watches ice hockey in a town that doesn’t have cell phone coverage, Obama goes to a tractor pull.

It’s as if presidential campaigns and their pursuing tagcloud of media pundits are actually a kind of landscape detection society – a rival Center for Land Use Interpretation – seeking out obsolete spatial versions of the United States, outdated geographies most of us no longer live within or encounter.

They find small towns that, by definition, are under-populated and thus unrepresentative of the United States as a whole; they find “old-fashioned” restaurants that seem on the verge of closing for lack of interested customers; they tour “Main Streets” that lost their inhabitants and their businesses long ago.

All along they pretend that these landscapes are politically relevant.

My point here is not that we should just swap landscapes in order to be in touch with the majority of the American population – going to this city instead of to that town, visiting this urban football team instead of that rural hockey league, stopping by this popular Asian restaurant instead of that pie-filled diner (though I would be very interested to explore this hypothesis). I simply want to point out that political campaigning in the United States seems almost deliberately to take place in a landscape that no longer has genuine relevance to the majority of U.S. citizens.

The idea that “an old-fashioned soda shop” might give someone access to the mind of the United States seems so absurd as to be almost impossible to ridicule thoroughly.

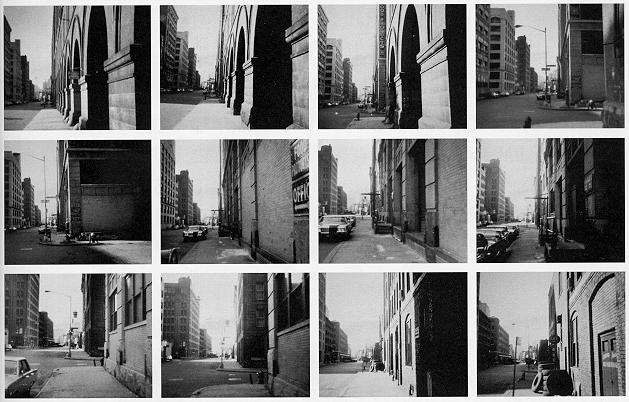

[Images: From the fascinating series of electoral maps produced by M. T. Gastner, C. R. Shalizi, and M. E. J. Newman after the 2004 U.S. presidential election].

[Images: From the fascinating series of electoral maps produced by M. T. Gastner, C. R. Shalizi, and M. E. J. Newman after the 2004 U.S. presidential election].

Of course, I understand that there are electoral college strategies at work and so on; but what I think remains unchallenged throughout all of this is the idea that small town voters somehow offer a more authentic perspective on the political life of this country – and not, say, people in West Hollywood or the Upper East Side or Atlanta or even Reno. Or World of Warcraft players. Or people who eat sushi. People who read Harry Potter novels.

“President Bush stopped off today with a group of people who read Harry Potter novels – the eleventh-largest demographic group in the United States – to discuss the ongoing financial crisis…”

Which group is larger, more important, more likely to vote, more demographically representative of the United States?

Call them micro-niches or whatever new marketing term you want to invent, but it seems like American politicians are increasingly trapped in a kind of minor landscape, a geography that is demonstrably not that within which the majority of Americans currently live.

“Barack Obama campaigned today in the early 1960s by visiting a small pancake house near Springdale…”

In any case, the entire political premise of the last eight years seems to have been one of landscape: big city dwellers near the Great Lakes and the ocean coasts simply don’t understand small town communities, and they’re embarrassingly out of touch with the everyday big skies of lonely ranchers on the plains. But while this might be true – and I don’t think it is, frankly – reversing this belief is surely even more alarming: the idea that someone whose background includes ranches and small towns should go on to lead an urban nation in an urban world seems questionable at best – and potentially dangerous in actual practice.

Again, though, there seems to be no adequate way to measure how political exposure to certain settled landscapes might affect a candidate’s ability to govern – and so this post should simply be taken as a kind of geographic speculation about democracy in the United States.

But it does raise at least one interesting group of questions, I think, including: what are the real everyday landscapes of American life, if those landscapes no longer include old-fashioned soda shops and small-town hockey arenas – or do such everyday landscapes simply no longer exist?

And if there are no everyday landscapes, then surely every landscape we encounter is, by definition, extraordinary – so we should perhaps all be paying more attention to the spatial and architectural circumstances of our daily lives?

Further, if political candidates have managed to discover – and to campaign almost exclusively within – an American landscape that seems not yet to have been touched by the trends and technologies of the twenty-first century, then why is that – and is it really a good indication that those candidates will know how to govern an urbanized, twenty-first century nation?

Finally, if urban candidates – or coastal candidates, whatever you want to call them – “don’t understand the west,” which is simply cultural code for not understanding small town life and for being out of touch with the moral hardships of the American countryside, then surely that’s not altogether bad in a country that is 80% urbanized?

Put another way, it would certainly be frustrating to think that a candidate doesn’t understand how a cattle ranch or an alfalfa farm operates, or that a candidate has no experience with a small town and its parent-teacher associations and so on – but it is extraordinarily troubling to me to think that a candidate doesn’t understand how, say, New York City functions – or Chicago, or Los Angeles, Miami, Boston, San Francisco, Denver, Seattle, Atlanta, or Phoenix – let alone the globally active and thoroughly urbanized economic networks within which these and other international cities are enmeshed.

Surely, then, it is small town candidates and politicians with ranching backgrounds who are demonstrably unqualified for the leadership of an urban country?

Surely we need urban candidates for the twenty-first century?

[Image: Duncraig Castle, Scotland; photo by Margaret Salmon and Dean Wiand for The New York Times].

[Image: Duncraig Castle, Scotland; photo by Margaret Salmon and Dean Wiand for The New York Times]. [Image: Duncraig Castle, Scotland; photo by Margaret Salmon and Dean Wiand for The New York Times].

[Image: Duncraig Castle, Scotland; photo by Margaret Salmon and Dean Wiand for The New York Times]. [Image: The population density of the United States, ca. 2000, via

[Image: The population density of the United States, ca. 2000, via  [Image: A street in

[Image: A street in  [Image: Urban areas in the U.S. Map courtesy of

[Image: Urban areas in the U.S. Map courtesy of  [Images: From the

[Images: From the  I’m also pleased to announce that I’ll be on the jury for a design competition hosted in Chicago next month, brought to you by the

I’m also pleased to announce that I’ll be on the jury for a design competition hosted in Chicago next month, brought to you by the  [Image: Vito Acconci,

[Image: Vito Acconci,

[Image: An artificial island in Austria, designed by

[Image: An artificial island in Austria, designed by  [Image: Vito Acconci, from

[Image: Vito Acconci, from  I picked up a few books yesterday afternoon at a

I picked up a few books yesterday afternoon at a  [Images: O.G.S. Crawford and his aerially archaeological airplane; a view of the countryside from above, where remnants of history cast long shadows].

[Images: O.G.S. Crawford and his aerially archaeological airplane; a view of the countryside from above, where remnants of history cast long shadows]. [Images: The cover of, and spreads from,

[Images: The cover of, and spreads from,

[Images: Object 02, including two interesting

[Images: Object 02, including two interesting  The

The  [Image: The

[Image: The  There are

There are  The

The  [Image:

[Image:  [Image: A new wing for the Museum of Photography in Charleroi by

[Image: A new wing for the Museum of Photography in Charleroi by

[Images: A new wing for the Museum of Photography in Charleroi by

[Images: A new wing for the Museum of Photography in Charleroi by  [Image: A new wing for the Museum of Photography in Charleroi by

[Image: A new wing for the Museum of Photography in Charleroi by

[Images: A new wing for the Museum of Photography in Charleroi by

[Images: A new wing for the Museum of Photography in Charleroi by  [Image: A new wing for the Museum of Photography in Charleroi by

[Image: A new wing for the Museum of Photography in Charleroi by  [Image: A new wing for the Museum of Photography in Charleroi by

[Image: A new wing for the Museum of Photography in Charleroi by