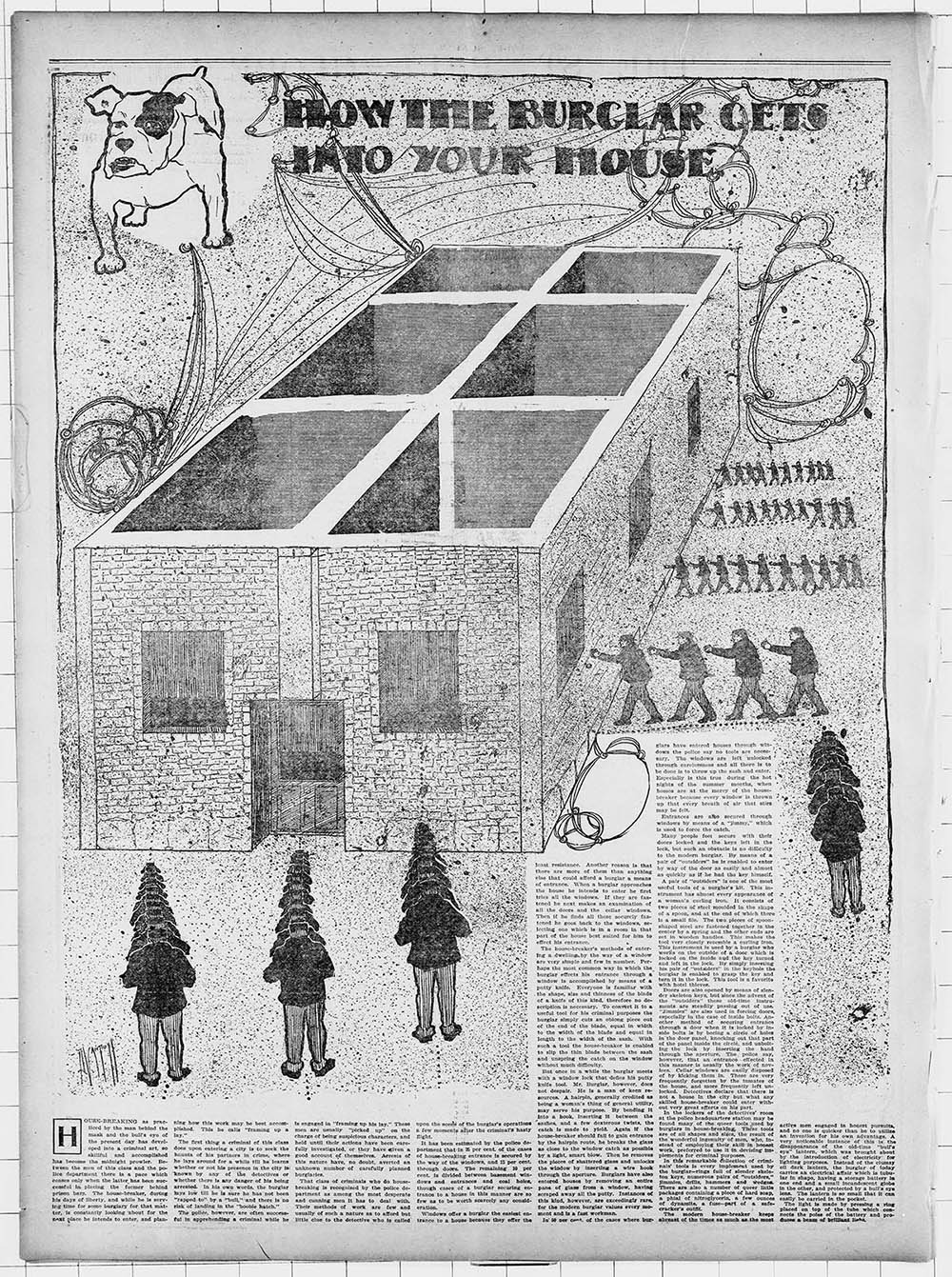

[Image: “How The Burglar Gets Into Your House” (1903), via The Saint Paul Globe].

[Image: “How The Burglar Gets Into Your House” (1903), via The Saint Paul Globe].

One unfortunate side-effect of the Greek financial crisis has been a rise in domestic burglaries. This has been inspired not only by a desperate response to bad economic times, but by the fact that many people have withdrawn their cash from banks and are now storing their cash at home.

As The New York Times reported at the end of July, “in the weeks before capital controls were imposed at the end of June, billions of euros fled the Greek banking system. Greeks feared that their euro deposits might be automatically converted to a new currency if Greece left the eurozone and would quickly lose value, or that they would face a ‘haircut’ to their accounts if their bank failed amid the stresses of the crisis.”

This had the effect that, while the rich simply shifted their assets overseas or into Swiss bank accounts, “the middle class has stashed not just cash but gold and jewelry, among other valuables, under the proverbial mattress.” Now, however, those “hidden valuables had become enticing targets for thieves.”

Or, more accurately, for burglars.

Burglary is a spatial crime: its very definition requires architecture. By entering an architectural space, whether it’s a screened-in porch or a megamansion, theft or petty larceny becomes burglary, a spatially defined offense that cannot take place without walls and a roof.

[Image: A street in Athens, via Wikipedia].

[Image: A street in Athens, via Wikipedia].

In any case, while Greece sees its burglary rate go up and reports of local break-ins rise, home fortification has also picked up pace. “Many apartment doors have sprouted new security locks with heavy metal plates, similar to the locks used in safes,” we read, and razor wire now “bristles from garden gates where there were none last summer.”

This vision of DIY security measures applied to high-rise residential towers and other housing blocks in Athens is a surprising one, considering that, globally, burglary is in such decline that The Economist ran an article a few years ago asking, “Where have all the burglars gone?”

As it happens, I’ve been studying burglary for the past few years for many reasons; among those is the fact that burglary offers insights into otherwise overlooked possibilities for reading and navigating urban and architectural space.

Indeed, burglary’s architectural interest comes not from its ubiquity, but from its unexpected, often surprisingly subtle misuse of the built environment. Burglars approach buildings differently, often seeking modes of entry other than doors and approaching buildings—whole cites—as if they’re puzzles waiting to be solved or beaten.

Consider the recent case of Formula 1 driver Jenson Button, whose villa in the south of France was broken into; the burglars allegedly made their entrance after sending anesthetic gas through the home’s air-conditioning system, incapacitating Button and his wife.

Although the BBC reports some convincing skepticism about Button’s claim, Button’s own spokesperson insists that this method of entry is on the rise: “The police have indicated that this has become a growing problem in the region,” the spokesperson said, “with perpetrators going so far as to gas their proposed victims through the air conditioning units before breaking in.”

There are other supposed examples of this sort of attack. Also from the BBC:

Former Arsenal footballer Patrick Vieira said he and his family were knocked out by gas during a 2006 raid on their home in Cannes. And in 2002, British television stars Trinny Woodall and Susannah Constantine said they were gassed while attending the Cannes Film Festival.

Other accounts, particularly from France, have appeared in the media over the past 15 years or so, describing people waking up groggy to discover they slept through a raid.

It’s worth noting, on the other hand, that actual proof of these home gas attacks is lacking; what’s more, the amount of anesthetic needed to knock out multiple adults in a large architectural space is prohibitively expensive to obtain and also presents a high risk of explosion.

Nonetheless, a security firm called SRX has commented on the matter, saying to the BBC that this is a real risk and even pointing out the specific vulnerability: ventilation intake fans usually found on the perimeter of a property, where they can be visually and acoustically shielded in the landscaping.

Their very inconspicuousness also “makes them ideal for burglars,” however, as homeowners can neither see nor hear if someone is tampering with them; as SRX points out, “we have to try and prevent access to those fans.”

Fortified air-conditioning intake fans. Razor wire defensive cordons on urban balconies. Reinforced front doors like something you’d find on a safe or vault.

[Image: A totally random shot of A/C units, via Wikipedia].

[Image: A totally random shot of A/C units, via Wikipedia].

The subject of burglary, break-ins, and home fortification interests me enough that I’ve written an entire book about it—called A Burglar’s Guide to the City, due out next spring from FSG—but it is also something I’ve addressed in an ongoing three-part series about domestic home security for Dwell magazine.

The second of those three articles is on newsstands now in the September 2015 issue, and it looks at the design and installation of safe rooms, more popularly known as panic rooms.

That article is not yet online—I’ll add a link when it’s up—but it includes interviews with safe room design experts on both U.S. coasts, as well as some interesting anecdotes about trends in home fortification, such as installing “lead-lined sheetrock to protect against radioactive attack.” Bullet-proof doors, rocket-propelled grenades, and home biometric security systems all make an unsettling appearance, as well.

Prior to that, in the July/August 2015 issue, I looked at technical vulnerabilities in smart home design. There, among other things, you can read that the “$20,000 smart-home upgrade you just paid for? It can now be nullified for about $400,” using a wallet-size device engineered by Drew Porter of Red Mesa.

Further, you’ll learn how “specific combinations of remote-control children’s toys could be hacked by ambitious burglars to do everything from watching you leave on your next vacation to searching your home for hidden valuables.” That’s all available online.

The final article in that three-part series comes out in the October 2015 issue. Check them all out, if you get a chance, and then don’t forget to pick up a copy of A Burglar’s Guide to the City next spring.