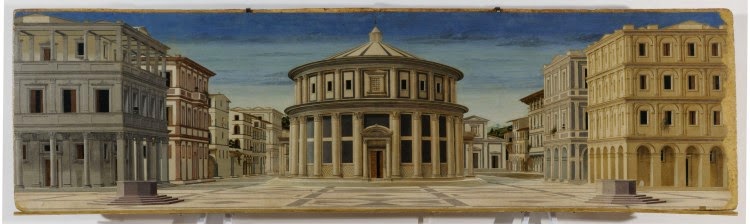

[Image: A perspectival representation of the “ideal city,” artist unknown].

[Image: A perspectival representation of the “ideal city,” artist unknown].

There’s an interesting throwaway line in The Verge‘s write-up of yesterday’s Amazon phone launch, where blogger David Pierce remarks that the much-hyped public unveiling of Amazon’s so-called Fire Phone was “oddly focused on art history and perspective.”

As another post at the site points out, “Amazon CEO Jeff Bezos likened it to the move from flat artwork to artwork with geometric perspective which began in the 14th century.”

These are passing comments, sure, and, from Amazon’s side, it’s more marketing hype than anything like rigorous phenomenological theorizing. Yet there’s something strangely compelling in the idea that a seemingly gratuitous new consumer product—just another smartphone—might actually owe its allegiance to a different technical lineage, one less connected to the telecommunications industry and more from the world of architectural representation.

[Image: Jeff Bezos as perspectival historian. Courtesy of The Verge].

[Image: Jeff Bezos as perspectival historian. Courtesy of The Verge].

It would be a smartphone that takes us back to, say, Albrecht Dürer and his gridded drawing machines, making the Fire Phone a kind of perspectival object that deserves a place, however weird, in architectural history. Erwin Panofksy, we might say, would have used a Fire Phone—or at least he would have written a blog post about it.

In this context, the amazing image of billionaire Jeff Bezos standing on stage, giving a kind of off-the-cuff history of perspectival rendering surely belongs in future works of architectural history. Smiling and schoolteacher-like, Bezos gestures in front of an infinite grid ghosted-in over this seminal work of urban scenography, in one moment aiming to fit his product within a very particular, highly Western tradition of representing the built environment.

[Image: Courtesy of The Verge].

[Image: Courtesy of The Verge].

The launch of the Fire Phone did indeed give perspectival representation its due, showing how a three-dimensionally or relationally accurate perception of geometric space can change quite dramatically with only a small move of the viewer’s own head.

The phone’s “dynamic perspective,” engineered to correct this, seems a little rickety at best, but it is meant as way to account for otherwise inconsequential movements of the viewer through the landscape, whether it’s a crowded city street or the vast interiors of a hotel. To do so requires an almost comical amount of technical hand-waving. From The Verge:

The key to making dynamic perspective work is knowing exactly where the user’s head is at all times, in real time, many times per second, Bezos said. It’s something that the company has been working on for four years, and [the] best way to do it is with computer vision, he went on to note. The single, standard front-facing camera wasn’t sufficient because its field of view was too narrow—so Amazon included four additional cameras with a much wider field of view to continuously capture a user’s head. At the end of the day, it features four specialized front-facing cameras in addition to the standard front-facing camera found near the earpiece, two of which can be used in case the other cameras were covered; it uses the best two at any given time. Lastly, Amazon included infrared lights in each camera to allow the phone to work in the dark.

Five hundred years ago, we’d instead be reading about some fabulous new system of mirrors, lens, prisms, and strings, all tied back to or operated by way of complexly engineered works of geared furniture. Unfolding tables and adjustable chairs, with operable flaps and windows.

[Image: One of several perspectival objects—contraptions for producing spatially accurate drawings—by Albrecht Dürer].

[Image: One of several perspectival objects—contraptions for producing spatially accurate drawings—by Albrecht Dürer].

These precursors of the Fire Phone, after seemingly endless acts of fine-tuning, would then, and only then, allow their users to see the scene before them with three-dimensional accuracy.

Now, replace those prisms and mirrors with multiple forward-facing cameras and infrared sensors, and market the resulting object to billions of potential users in front of gridded scenes of Western urbanism, and you’ve got the strange moment that happened yesterday, where a smartphone aimed to collapse all of Western art history into a single technical artifact, a perspectival object many of us will soon be carrying in our bags and pockets.

[Image: Another “ideal city,” artist unknown].

[Image: Another “ideal city,” artist unknown].

More interestingly, though, with its odd focus “on art history and perspective,” Amazon’s event raises the question of how electronic mediation of the built environment might be affecting how our cities are designed in the first place—how we see buildings, streets, and cities through the dynamic lens of automatic perspective correction and other visual algorithms.

Put another way, is there a type of architecture—Classical, Romanesque—particularly well-suited for perspectival objects like the Fire Phone, and, conversely, are there types of built space that throw these devices off altogether? Further, could artificial environments that exceed the rendering capacity of smartphones and other digital cameras be deliberately designed—and, if so, what would they “look like” to those sensors and objects?

Recall that, at one point in his demonstration, Bezos explained how Amazon’s new interface “uses different layers to hide and show information on the map like Yelp reviews,” effectively tagging works of architecture with digital metadata in a kind of Augmented Reality Lite.

But what this suggests, together with Bezos’s use of “ideal city” imagery, is that smartphone urbanism will have its own peculiar stylistic needs. Perhaps, if visually defined, that will mean that phones will require cities to be gridded and legible, with clear spatial differentiation between buildings and objects in order to function most accurately—in order to line up with the clouds of virtual tags we will soon be placing all over the structures around us. Perhaps, if more GPS-defined, that will mean overlapping buildings and spaces are just fine, but they nonetheless must allow unblocked access to satellite signals above so that things don’t get confused down at street level—a kind of celestial perspectivism where, from the phone’s point of view, the roof is the new facade, the actual “front” of the building through which vital navigational signals must travel.

Either way, the possibility that there is a particular type of space, or a particular type of urbanism, most suited to the perspectival needs of new smartphones is totally fascinating. Perhaps in retrospect, this photograph of Jeff Bezos, grinning at the world in front of a gigantic image of Western perspective, will become a canonical architectural image of where digital objects and urban design intersect.