[Image: A screenshot from Fracture by LucasArts. Via Wired].

[Image: A screenshot from Fracture by LucasArts. Via Wired].

Over on Wired this weekend I read about a game called Fracture, by LucasArts, which features “terrain deformation” as a central factor in gameplay.

Fracture is “a game centered on the wanton reformation of land masses,” Wired reports; the author then goes on to introduce us to the game’s “terrain deformation mechanics.”

“Every player is equipped with a tool called an Entrencher,” we read. The Entrencher “gives them the ability to raise or lower most surfaces at will,” including the surface of the earth itself:

Gone are the days of studying a level, and simply memorizing sniper positions and the fastest routes. Resourceful players will be digging trenches, raising their own cover and manipulating level elements to fortify their positions… fundamentally altering the way levels are played.

Which means what, exactly?

Can’t find a way across that slime pit? Raise the ground underneath it. You can also terrain-jump by leaping as you raise the ground beneath your feet, launching yourself into the air.

“The rule of thumb,” the article adds, “is that if you can walk on it, you can probably alter it.”

Using weapons like the Tectonic Grenade, you can reshape the planet. Quoting from the official Fracture website:

The ER23-N Tectonic Grenade sets off localized shockwaves when detonated, causing small, concentrated earthquakes that raise the immediate terrain around the point of impact. The weapon is extremely useful for shaping the terrain and providing cover.

There’s also a Spike Grenade. As LucasArts explains, “Tectonic scientists discovered that lava tubes lying dormant deep below the surface of the earth could be stimulated to eject a pyroclastic column.” These columns can “be used as a ‘natural elevator’ of sorts, allowing a soldier to access hard to reach high elevation areas.”

[Image: A screenshot from Fracture, by LucasArts, showing a pyroclastic elevator at work].

[Image: A screenshot from Fracture, by LucasArts, showing a pyroclastic elevator at work].

There are even Subterranean Torpedoes that burrow into the planet and create landforms on the surface far away.

[Image: A screenshot from Fracture by LucasArts].

[Image: A screenshot from Fracture by LucasArts].

Of course, the idea that an instantaneous and semi-magmatic reshaping of the earth’s surface might have military implications is an interesting one – and probably not far from technological realization. I’ve written about the weaponization of the earth’s surface before, but Fracture seems to illustrate the concept in a refreshingly accessible way.

However, there are many historical precedents for the idea of politicized terrain creation, and these deserve at least a passing mention here.

I’m thinking, in particular, of David Blackbourn’s recent book The Conquest of Nature: Water, Landscape, and the Making of Modern Germany. The “making” in Blackbourn’s subtitle is meant literally, as the book looks at coastal reshaping, bog- and marsh-draining, and other projects of imperial hydrology; these were the activities through which the territory of Germany itself was physically shaped.

It was terrain deformation: a militarized reshaping of the earth’s surface under orders from Frederick the Great. Frederick sought to transform the lands of northern Germany – then called Prussia – in order to create more space to rule.

In his book, Blackbourn describes what these imperial “hydro-technicians” actually did:

The task of filling in the squares on Frederick’s grids remained. That meant ditching and diking the future fields, constructing sluices, uprooting the old vegetation and planting willows by the new drainage canals, preparing the still heavy, intractable soil, building paths and bridges, houses, farms, and schools, all the while maintaining the new defenses against the water.

These “new defenses” have since been so naturalized that we mistake them for a pre-existing terrain upon which modern Germany was founded – but they were and are constructed landforms, a “brave new world of dikes, ditches, windmills, fields, and meadows.”

These were lands created through military intervention in order to host a particular form of political governance.

In this context, then, Fracture would seem to be simply an accelerated – or what Sanford Kwinter might call an “adrenalated” – version of this tactical landscaping.

[Image: Celestial Impact].

[Image: Celestial Impact].

Meanwhile, a commenter over on Wired points out that there are conceptual similarities between Fracture and another game called Celestial Impact.

In Celestial Impact, “the landscape is fully deformable in all directions.”

“Build and dig your way around the landscape in various strategic ways,” we read, ways that are “not limited to destruction”:

[T]he players also have the ability to add terrain to the landscape in the middle of combat using a special tool called Dirtgun. With the Dirtgun, players can add or remove terrain during combat as they see fit, simply by aiming and firing the dirtgun. Depending on the chosen action, this will either add or remove a chunk of dirt from the landscape. So as the teams are battling, the landscape receives vast changes opening up for various tactical approaches each team can use.

When your weapons are set on build-mode, the game’s creators explain, “the Dirtgun adds terrain in the form of a pre-selected shape in front of the player. The shapes could be a simple cube, a part of a bridge or even a defensive wall.”

In many ways, this sounds like a weaponized version of Behrokh Khoshnevis‘s building-printer – subject of one of the earliest posts on BLDGBLOG – here remade as a kind of propulsive instant-concrete mixer retrofit for imperial military campaigns.

As Discover described Khoshnevis’s machine back in 2005, “a robotically controlled nozzle squeezes a ribbon of concrete onto a wooden plank. Every two minutes and 14 seconds, the nozzle completes a circuit, topping the previous ribbon with a fresh one. Thus a five-foot-long wall rises – a wall built without human intervention.”

Now make an accelerated, portable, and fully weaponized version of this thing, put it in a videogame, and you’ve got something a bit like Celestial Impact.

Here are some screenshots.

[Image: From The re-naturalization of territory by Vicente Guallart].

[Image: From The re-naturalization of territory by Vicente Guallart].

Finally, I couldn’t help but think here of architect Vicente Guallart. Guallart’s work consistently seeks to introduce new geological forms into the built infrastructure of the city – artificial mountains, for instance, and “new topographies” through which a city might expand.

[Image: From The re-naturalization of territory by Vicente Guallart].

[Image: From The re-naturalization of territory by Vicente Guallart].

I suppose one question here might be: what would a videogame look like as designed by Vicente Guallart? Would it look like Fracture? If Vicente Guallart and Behrokh Khoshnevis teamed up, would they have created Celestial Impact?

But a more interesting, and wide-ranging, question is whether designing videogame environments is not something of a missed opportunity for today’s architecture studios.

After all, how might architects relay complex ideas about space, landscape, and the design of new terrains if they were to stop using academic essays and even project renderings and turn instead to video games?

It seems like you can take your ideas about terrain deformation and instant landscapes and nomadic geology and you can license it to LucasArts, knowing that tens of thousands of people will soon be interacting with your ideas all over the world; or you can just pin some images up on the wall of an architecture class, make no money at all, and be forced to get a job rendering buildings for Frank Gehry.

So would more people understand Rem Koolhaas’s thoughts on cities if he stopped writing 1000-page books and started designing videogames – games set in some strange quasi-Asiatic desert world of Koolhaasian urbanism?

Or do all of these questions simply mistake popularity for engaged comprehension?

The larger issue, though, is whether or not architecture, increasingly popular as a kind of Dubai-inspired freakshow (rotating skyscrapers! solar-powered floating hotels!), is nonetheless not reaching the audience it needs.

[Image: From The re-naturalization of territory by Vicente Guallart].

[Image: From The re-naturalization of territory by Vicente Guallart].

If architects and architecture writers continue to use outmoded forms of publication, such as $25/copy university-sponsored magazines and huge books purchased by no one but college librarians, then surely they can expect only people currently enrolled in academic programs even to be aware of what they’re talking about, let alone to be enthusiastic about it or appreciative of the implications.

$100 hardcover books do absolutely nothing to increase architecture’s audience.

So what would happen if architects tried videogames?

[Image: The constructed geologies of Vicente Guallart, from How To Make a Mountain].

[Image: The constructed geologies of Vicente Guallart, from How To Make a Mountain].

In any case, terrain deformation, dirtguns set on build-mode, and other forms of militarized landscape creation – these seem like good enough reasons to me to add gaming consoles to a design syllabus near you.

[Image: The cover of Floater Magazine #01; view larger].

[Image: The cover of Floater Magazine #01; view larger]. [Image: Le Corbusier’s Maison Citrohan undergoes speculative regulatory alterations, as applied by Finn Williams and David Knight].

[Image: Le Corbusier’s Maison Citrohan undergoes speculative regulatory alterations, as applied by Finn Williams and David Knight]. [Image: View

[Image: View  [Image: View

[Image: View  [Image: New flats, part of the AHMM master plan in Barking, England, specifically cited by the BBC as being so small that they’re mere slums in the making; via

[Image: New flats, part of the AHMM master plan in Barking, England, specifically cited by the BBC as being so small that they’re mere slums in the making; via  I’m excited to announce that I’ll be speaking on a panel at the upcoming

I’m excited to announce that I’ll be speaking on a panel at the upcoming  [Image: Panel description; view

[Image: Panel description; view  [Image: A view of the

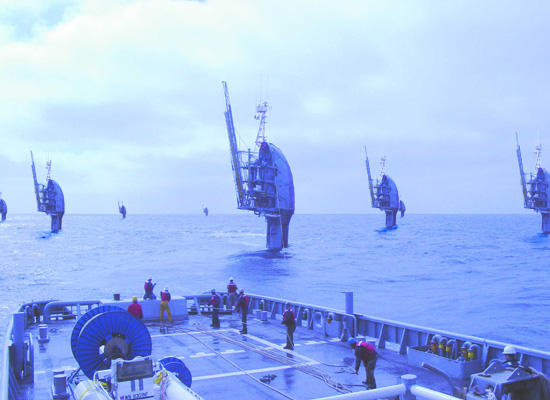

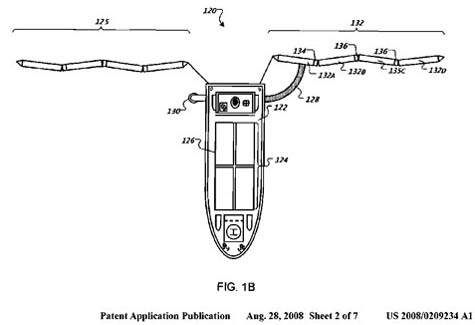

[Image: A view of the  [Image: From Google’s patent application for servers at sea; via the

[Image: From Google’s patent application for servers at sea; via the  [Image: The Instant City at work; diagrams by

[Image: The Instant City at work; diagrams by  [Image: Karen Brown/

[Image: Karen Brown/ [Image: Airbus A380, photographed by Robyn Beck/Agence France-Presse for Getty Images, via the

[Image: Airbus A380, photographed by Robyn Beck/Agence France-Presse for Getty Images, via the  [Images: Photos by Brett Boardman, for the

[Images: Photos by Brett Boardman, for the  [Image: An etching by

[Image: An etching by  [Image: A screenshot from

[Image: A screenshot from  [Image: A screenshot from

[Image: A screenshot from  [Image: A screenshot from

[Image: A screenshot from  [Image:

[Image:  [Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: The constructed geologies of

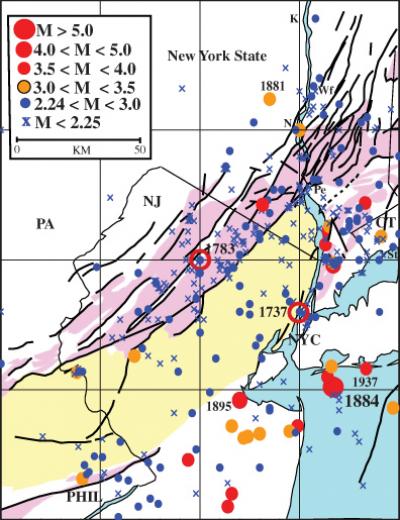

[Image: The constructed geologies of  [Image: A seismic map of the mid-Atlantic, via

[Image: A seismic map of the mid-Atlantic, via