The L.A. Times reports that, “Over the next six months, a budget-induced employee retirement program will shrink [L.A.’s] civilian workforce—a group that excludes the Department of Water and Power—by at least 9%. Some policymakers have only begun grasping the magnitude of the exodus of librarians, building inspectors, traffic officers, city planners and other workers, many of them the city’s most experienced employees.”

Imagining Los Angeles without “librarians, building inspectors, traffic officers, [and] city planners” will sound, to many, as if nothing has changed in the city at all—but this governmental downsizing comes just as speculation about California’s impending bankruptcy grows.

[Image: “free” by Flickr-user Fliegender, from the Lost Angeles set].

[Image: “free” by Flickr-user Fliegender, from the Lost Angeles set].

Two months ago, the Guardian, paraphrasing historian Kevin Starr, asked whether California might actually become “America’s first failed state“—a question that generated nearly 7500 comments on the Huffington Post.

“The state that was once held up as the epitome of the boundless opportunities of America has collapsed,” the Guardian writes.

From its politics to its economy to its environment and way of life, California is like a patient on life support. At the start of summer the state government was so deeply in debt that it began to issue IOUs instead of wages. Its unemployment rate has soared to more than 12%, the highest figure in 70 years. Desperate to pay off a crippling budget deficit, California is slashing spending in education and healthcare, laying off vast numbers of workers and forcing others to take unpaid leave.

Yet, for the time being, water stills flows from California’s taps, the traffic signals still work, and rural towns still have electricity—but what might happen if California really did “collapse”? What would it look like if the state actually did declare bankruptcy, defaulting on billions of dollars in public debt?

[Image: “the lot” by Flickr-user Fliegender, from the Lost Angeles set].

[Image: “the lot” by Flickr-user Fliegender, from the Lost Angeles set].

Newgeography.com attempted to answer a variation on that question in an article posted several days ago:

Ideally, we’d see a court-supervised, orderly bankruptcy similar to what we see when a company defaults. All creditors, including direct lenders, vendors, employees, pensioners, and more would share in the losses based on established precedent and law. Perhaps salaries would be reduced. Some programs could see significant changes. (…) Unfortunately, a formal bankruptcy is not the likely scenario. There is no provision for it in the law. Consequently, absent framework and rules of bankruptcy, the eventual default is likely to be very messy, contentious and political.

The article continues, raising the stakes:

The worst case would be the mother of all financial crises. According to the California State Treasurer’s office, California has over $68 billion in public debt, but the Sacramento Bee’s Dan Walters has tried to count total California public debt, including that of local municipalities, and his total reaches $500 billion.

It’s worth bearing in mind here that recent economic shocks caused by the fear that Dubai might default on its debt involved a mere $59 billion; nonetheless, Bank of America analysts, according to the New York Times, suggested that Dubai’s debt could “escalate into a major sovereign default problem, which would then resonate across global emerging markets in the same way that Argentina did in the early 2000s or Russia in the late 1990s.” In other words, a $500 billion default by the state of California—if that’s indeed what the numbers turn out to be—would clearly have near-catastrophic effects on world markets.

In any case, Newgeography.com takes us all the way up to the brink, speculating that “the worst case is also the more likely case.” After all, “every month brings new bad news” about the state of things in California, and “the risk” is that “one of those news events triggers a crisis.”

[Image: “temple” by Flickr-user Fliegender, from the Lost Angeles set].

[Image: “temple” by Flickr-user Fliegender, from the Lost Angeles set].

But what will this crisis actually look like? What really is the worst case scenario? Detroit? John Steinbeck? New York in the 1970s? Bosnia?

Possible clues to this future landscape come to us from all directions, frankly, with articles about the housing crisis alone supplying horrific visions of homeowner suicide, copper-thieving gangs tearing apart foreclosed houses in a quest for scrap metal, abandoned swimming pools turning into mosquito-breeding grounds, and even wildcats moving down from the mountains to take over empty cul-de-sacs, like some strange new Disney film awaiting its screenplay’s green light.

Sticking with the articles I’ve already cited here, however, the Guardian offers some details of this emerging world, describing “a travelling medical and dental clinic” set-up inside a Los Angeles venue for rock concerts; 500,000 people moving out of the state to seek jobs elsewhere; entire towns destroyed by alcoholism and near-50% unemployment; and “a squatter’s camp of newly homeless labourers sleeping in their vehicles” that “has grown up in a supermarket car park—the local government has provided toilets and a mobile shower.”

So what new cultures, forms of settlement, and even, generations from now, new religions might spring up from these convulsions of economic geography? Less abstractly, if the Los Angeles Police Department is defunded to half its size, what will start to happen in the city? If the sewers aren’t cleaned and the bridges break down and the bus services halt, what will actually happen?

Of course, it’s worth pointing out that, for many Angelenos, the situation described here—with its lack of police security, broken infrastructure, no public transport, and an “exodus of librarians”—has already arrived, and it’s called everyday life.

[Image: “anjac” by Flickr-user Fliegender, from the Lost Angeles set].

[Image: “anjac” by Flickr-user Fliegender, from the Lost Angeles set].

But there is a part of me undeniably fascinated by what we might call DIY, Kim Stanley Robinson-esque, quasi-anarchic salvage cultures—Mad Max meets Mickey Muennig, say—but it’s one thing to foresee a new, post-collapse Californian urbanism in which neighbors happily come together to manage community gardens and sidewalk-repaving projects and quite another to think that MAKE-reading locals in the year 2015 might successfully repair the Bay Bridge using hand-me-down home toolkits.

However, it’s too easy to rely on fantasies of violent apocalypse here—with visions of U.S. cities given over to gang warfare and mass rape, their outer suburbs scoured clean by wildfires, huge blooms of unfiltered sewage filling the waters of Marina del Rey, whole neighborhoods walled off in experiments with micro-sovereignty, drug lords ensconced behind machine gun nests in the Hollywood Hills (while federal troops sleep in derelict movie theaters in the valleys below…). All of it shivering with the odd 7.0 earthquake.

While that does make for an intriguing science fiction scenario, I’ve conversely been very strongly struck by Rebecca Solnit’s new, if quite uneven (and excessively anti-military) book A Paradise Built in Hell.

Solnit’s basic thesis is that, throughout history, public disasters have actually inspired the formation of altruistic communities based in generosity and cooperation—that, “in the wake of an earthquake, a bombing, or a major storm, most people are altruistic, urgently engaged in caring for themselves and those around them, strangers and neighbors as well as friends and loved ones. The image of the selfish, panicky, or regressively savage human being in times of disaster has little truth to it.” With this in mind, then, how do we realistically predict—even architecturally represent—California as a state in genuine free-fall?

[Image: “chinatown” by Flickr-user Fliegender, from the Lost Angeles set].

[Image: “chinatown” by Flickr-user Fliegender, from the Lost Angeles set].

I’m torn here between two very different but equally compelling visions of what might happen if such circumstances were to arise.

On the one hand, there is Solnit. She describes the informal urbanism and flexible infrastructures of street hospitals and soup kitchens, strangers helping strangers through the half-ruined streets of cities darkened by blackouts. There are “disaster utopias,” she writes, and “Citizens themselves in these moments constitute the government—the active decision-making body—as democracy has always promised and rarely delivered.”

These remarkable societies suggest that, just as many machines reset themselves to their original settings after a power outage, so human beings reset themselves to something altruistic, communitarian, resourceful, and imaginative after a disaster, that we revert to something we already know how to do. The possibility of paradise is already within us as a default setting.

Solnit puts great emotional emphasis on this latter point throughout the book: “The possibility of paradise hovers on the cusp of coming into being, so much so that it takes powerful forces to keep such a paradise at bay.”

Of course, the disasters to which Solnit refers are, by definition, temporary—so the giddiness that she perceives as coextensive with the human spirit might simply be a fleeting sense that one has to take advantage of unexpected conditions, like a sunny day in Cole Valley, while they last. Several decades of living amidst rubble might make those early nights out barbecuing in the streets with strangers seem oddly naive in retrospect.

Because then, on the other hand, there is something Kim Stanley Robinson said in an interview with BLDGBLOG two years ago. This offers a very dramatic counterpoint. Quoting Robinson at length:

For one thing, modern civilization, with six billion people on the planet, lives on the tip of a gigantic complex of prosthetic devices—and all those devices have to work. The crash scenario that people think of, in this case [specifically, global climate change and civilizational collapse], as an escape to freedom would actually be so damaging that it wouldn’t be fun. It wouldn’t be an adventure. It would merely be a struggle for food and security, and a permanent high risk of being robbed, beaten, or killed; your ability to feel confident about your own—and your family’s and your children’s—safety would be gone. People who fail to realize that… I’d say their imaginations haven’t fully gotten into this scenario.

The obvious answer to the many rhetorical questions in this post is that there will be varying degrees of each of these scenarios, in different locations at different times, involving different people for unpredictable reasons.

[Image: “A group of young men watch the Station fire from a hill overlooking Tujunga. The fire, which began Aug. 26 near the Angeles Crest Highway, killed two firefighters and burned more than 160,000 acres. The cause of the blaze, which burned 250 square miles of the Angeles National Forest, was arson, officials said.” Photo by Wally Skalij for The Los Angeles Times].

[Image: “A group of young men watch the Station fire from a hill overlooking Tujunga. The fire, which began Aug. 26 near the Angeles Crest Highway, killed two firefighters and burned more than 160,000 acres. The cause of the blaze, which burned 250 square miles of the Angeles National Forest, was arson, officials said.” Photo by Wally Skalij for The Los Angeles Times].

But if the state of California goes into anything like long-term financial catastrophe (with no police, no fire departments, no hospitals, schools, electricity, clean water, and so on, even as I admit that my own descriptions gravitate toward sci-fi), how do we push this radical loss of infrastructure closer to Solnit than to Robinson?

How do we open what Solnit calls “the doorway in the ruins” and invent whole new urbanisms in the wake of economic collapse?

[Images: All images courtesy of Zebra Imaging].

[Images: All images courtesy of Zebra Imaging]. [Images: Inside

[Images: Inside  [Image: The Burj Dubai, photographed by Karim Sahib for the

[Image: The Burj Dubai, photographed by Karim Sahib for the  [Image: “

[Image: “ [Image: “

[Image: “ [Image: “

[Image: “ [Image: “

[Image: “ [Image: “

[Image: “ [Image: “A group of young men watch the

[Image: “A group of young men watch the  [Images: Three photos by

[Images: Three photos by  [Image: A photo of subsidence craters, the spatial aftermath of underground nuclear tests, taken by

[Image: A photo of subsidence craters, the spatial aftermath of underground nuclear tests, taken by  [Image:

[Image:

[Images: Two views of

[Images: Two views of  [Image: From

[Image: From

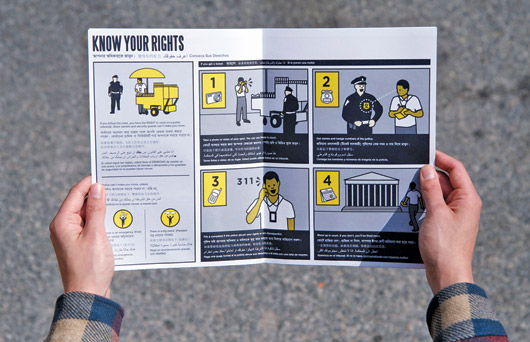

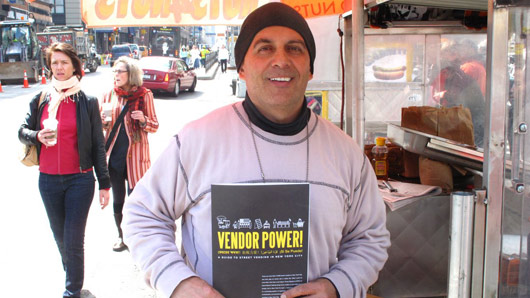

[Images: Vendors reading

[Images: Vendors reading  [Image: Tenants’ rights

[Image: Tenants’ rights

[Images: Tenants’ rights

[Images: Tenants’ rights  [Image: Tenants’ rights

[Image: Tenants’ rights

[Images: Tenants’ rights

[Images: Tenants’ rights  From sealing off your home ventilation system to turning the basement into a functioning medical ward—stashing “

From sealing off your home ventilation system to turning the basement into a functioning medical ward—stashing “ In any case, the setting:

In any case, the setting: Home preparation doesn’t end with filters, however; there is

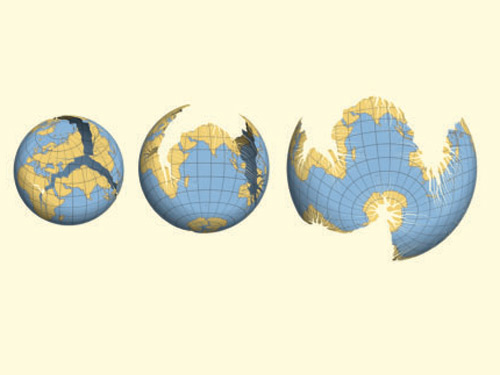

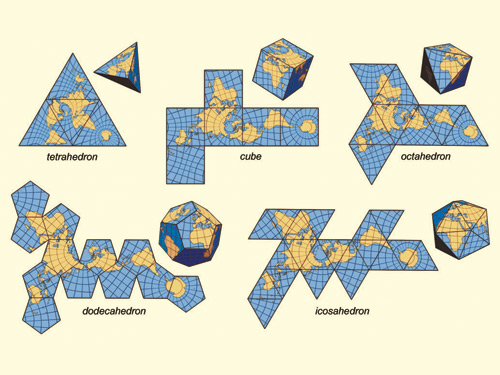

Home preparation doesn’t end with filters, however; there is  [Image: By Jack van Wijk, Eindhoven University of Technology].

[Image: By Jack van Wijk, Eindhoven University of Technology].

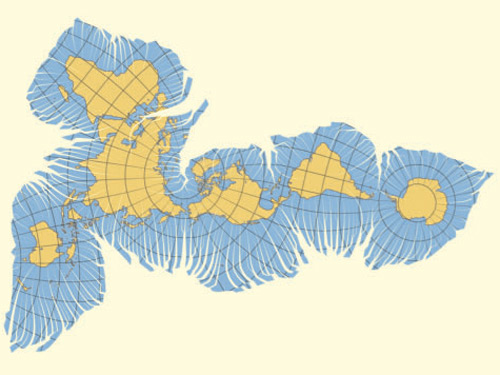

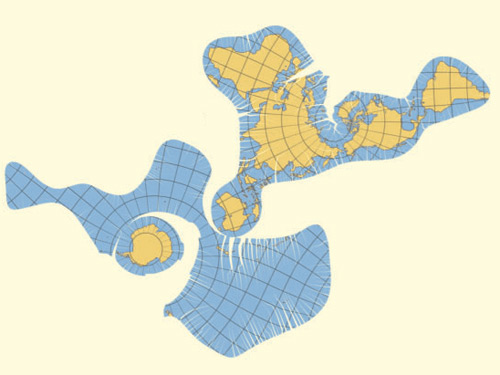

[Images: By Jack van Wijk, Eindhoven University of Technology].

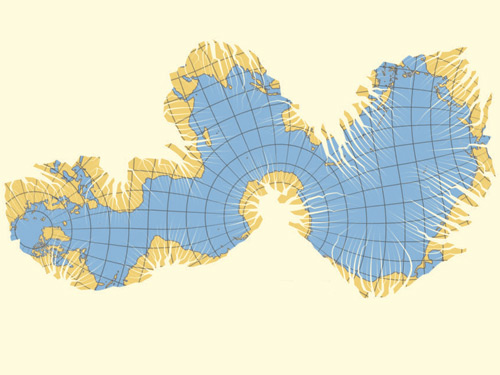

[Images: By Jack van Wijk, Eindhoven University of Technology]. [Image: The world as a near-continuous coastline around one global ocean. By Jack van Wijk, Eindhoven University of Technology].

[Image: The world as a near-continuous coastline around one global ocean. By Jack van Wijk, Eindhoven University of Technology]. [Image: And they ascend the antenna… Photographer unknown; photo from a 1969 issue of

[Image: And they ascend the antenna… Photographer unknown; photo from a 1969 issue of  At one such earthen event, participants are actually served “two or three wine glasses, each filled with soil from a different organic farm”—and these samplings of different geographies do matter. “In other words, if the earth on which your farm sits has ‘grassy,’ ‘olive,’ or ‘smoky’ notes, those flavours will recur in the organic spinach or goat’s milk cheese you produce. Smelling the soil first simply helps you become aware of the continuity.”

At one such earthen event, participants are actually served “two or three wine glasses, each filled with soil from a different organic farm”—and these samplings of different geographies do matter. “In other words, if the earth on which your farm sits has ‘grassy,’ ‘olive,’ or ‘smoky’ notes, those flavours will recur in the organic spinach or goat’s milk cheese you produce. Smelling the soil first simply helps you become aware of the continuity.”