[Image: The self-weaving complexity of I-95 and I-695, north of Baltimore].

[Image: The self-weaving complexity of I-95 and I-695, north of Baltimore].

For a variety of reasons, it seems worthwhile to do a kind of combined recap of my recent talks for the AIA in Baltimore and at the University of Pennsylvania. If you were present at either one of those events, then this should hopefully serve as a nice trip down memory lane; if you weren’t there, this should give at least some idea of the topics covered, themes discussed, images seen, and so on. Of course, if this sounds even remotely interesting, I’d be more than happy to give a similar talk at a venue near you… I’ve been having a blast doing these things.

In any case, I was in Baltimore two weeks ago on a joint invitation from the AIA and Preservation Maryland, to discuss architectural preservation, broadly conceived, with at least some relation to Baltimore proper.

So I began my lecture with a story from the science journals back in fall 2005. It turns out, we learned, that a specific highway junction north of Baltimore – where I-95 and I-695 meet – is topologically unique, exhibiting something called “non-trivial braiding.” However, because of that structure’s inefficiency as a traffic conveyor, the merging on- and off-ramps were going to be rebuilt, reconnected, and otherwise altered beyond mathematical recognition.

Its topology, in other words, would be ruined.

[Image: A diagram of the “non-trivial braiding” that awaits you on the eastern seaboard; via New Scientist].

[Image: A diagram of the “non-trivial braiding” that awaits you on the eastern seaboard; via New Scientist].

A little bit of roadwork, and that mathematical object would be gone.

“I don’t want to encourage more cars onto the roads,” New Scientist wrote, “but if topology and beauty mean anything to you, get out there and enjoy I-95/695 now. It may soon be too late.”

So the question becomes: at what point do we preserve something not for its historical value but for its topological interest? If a bridge, or a highway overpass, becomes functionally obsolete, is it still subject to the rules of architectural preservation – whether or not it’s mathematically unique or culturally intriguing? Surely infrastructure is just infrastructure – i.e. when it breaks you replace it? You don’t preserve infrastructure.

Or do you?

[Images: Google Maps of the famed intersection].

[Images: Google Maps of the famed intersection].

Meanwhile, at what point does the exchange value of culture and history trump the use value of function and design?

And should mathematicians have any say?

[Image: Knot diagrams by Robert Scharein. Could we treat these as infrastructural blueprints and redesign the U.S. highway system to form a catalog of complex knots? You could then study experiential mathematics from behind the wheel of your car…].

[Image: Knot diagrams by Robert Scharein. Could we treat these as infrastructural blueprints and redesign the U.S. highway system to form a catalog of complex knots? You could then study experiential mathematics from behind the wheel of your car…].

Perhaps there’s a middle ground here. Perhaps we can, in fact, preserve something like a highway traffic exchange without forcing people to use its outdated twists and turns.

This brings us to the idea of the stabilized ruin.

If we could remove the intersection, for instance, from everyday use and simply build around it, we could then stabilize it as a ruin – turning it into a kind of abstract sculptural form, like something by Barbara Hepworth – and, at the very least, create an interesting site for mathematically inclined tourists.

[Images: Three sculptures by Barbara Hepworth – build these big enough and they’d be pieces of urban infrastructure].

[Images: Three sculptures by Barbara Hepworth – build these big enough and they’d be pieces of urban infrastructure].

For visual reference here I mentioned architect Alberto Campo Baeza‘s 2002 proposal for a Mercedes Benz Museum. Might Campo Baeza’s structure be a model for what the I-95/695 intersection would look like if it was detached from the highway system and left alone, to be surrounded by new freeways?

It’d be a kind of modern-day Stonehenge, made from on-ramps, surrounded by wildflowers, with well-designed signs to explain its fine geometry. Loops of concrete in space.

[Images: Proposal for a Mercedes Benz Museum by Alberto Campo Baeza].

[Images: Proposal for a Mercedes Benz Museum by Alberto Campo Baeza].

Of course, there are other stabilized ruins – and here, trying to keep things regional, I pointed out Philadelphia’s Eastern State Penitentiary, highlighting photographs taken there by Shaun O’Boyle. We see some examples of O’Boyle’s work here in this post – and O’Boyle, of course, was featured in BLDGBLOG’s earlier look at Bannerman’s Island.

“After 142 years of consecutive use,” the penitentiary’s website explains, “Eastern State Penitentiary was completely abandoned in 1971, and now stands, a lost world of crumbling cell blocks and empty guard towers.” It was one of the only two U.S. sites that Charles Dickens went out of his way to visit, on a trip in 1842; the other was Niagara Falls.

[Images: Four photos of Eastern State Penitentiary, taken by Shaun O’Boyle].

[Images: Four photos of Eastern State Penitentiary, taken by Shaun O’Boyle].

So if stabilization is a viable preservation strategy, then what are its limits? What is too small to worry about – and what is too large even to consider?

Back in the late 1990s, photographer and urban sociologist Camilo José Vergara controversially proposed that a “skyscraper ruins park” be built in downtown Detroit. In his book American Ruins, Vergara suggested that, “as a tonic for our imagination, as a call for renewal, as a place within our national memory, a dozen city blocks of pre-Depression skyscrapers be stabilized and left standing as ruins: an American Acropolis.”

Continuing this line of thought in a later article for Metropolis, Vergara wrote:

We could transform the nearly 100 troubled building into a grand national historic park of play and wonder, an urban Monument Valley… Midwestern prairie would be allowed to invade from the north. Trees, vines, and wildflowers would grow on roofs and out of windows; goats and wild animals – squirrels, possum, bats, owls, ravens, snakes and insects – would live in the empty behemoths, adding their call, hoots and screeches to the smell of rotten leaves and animal droppings.

Of course, fantasies of ruined cities are alive and well, so to speak. One need only look as far as the disastrous film I Am Legend, or turn to Alan Wiseman’s recent bestseller The World Without Us to see that the appeal of dead cities never quite fades.

[Image: A poster for I Am Legend].

[Image: A poster for I Am Legend].

Indeed, I’m tempted here to pitch a new breed of entertainment complex to some oil-rich emir or investment group: the idea is that you would build a ruined city on the shores of an artificial island somewhere south of all the luxury developments in Dubai, and you’d invite tourists to explore those haunted canyons of steel and broken glass.

For the low-low price of only $75,000 a day, you can rent the entire park for yourself – and thus be Will Smith for a day, wandering through ruined department stores and sunbathing in weed-filled plazas.

At the very least, imagine the political implications of such a park: touring the ruins of the west by visiting Dubai – where the shattered remnants of Euro-America are nothing but a theme park for global tourists.

With recognizable buildings from London, New York, Chicago, Paris, Rome, and so on, I suppose it’d be a little like the film Resident Evil: Extinction, where we see the lost lights of Las Vegas buried in desert sand.

Only here it’s a simulacrum of the entire western world, and it’s laid out as waste at the feet of Dubai’s glass towers and air-conditioned boulevards.

[Image: A poster for Resident Evil: Extinction].

[Image: A poster for Resident Evil: Extinction].

In any case, with accidentally good timing, we moved on from there into a discussion of architect Albert Speer’s notorious plans for the Nazi super-city of Germania: a vision of what Berlin would become, given the presumed global triumph of Hitler and his skeletal empire. Of course, Speer’s by now well-known architectural theory was that all buildings should be designed so that they will look good in the future as ruins.

He called this ruin value.

I say “good timing” here, because Germania is actually the focus of a well-publicized exhibition in Berlin, going on right now, called Myth Germania. It comes complete with a detailed model of Speer’s urban vision – bits of which can be seen here in old photographs.

[Images: Albert Speer’s Germania].

[Images: Albert Speer’s Germania].

Although ruined cities appear again and again here on BLDGBLOG – and will continue to do so – there is a stage beyond ruin, something that comes after dereliction and abandonment. As long as we are willing to think along geological timescales, in other words, then we can talk about what I’ve called urban fossil value.

What will our cities look like when they have fossilized?

Who else but New Scientist approached this very topic nearly a decade ago, explaining that, hundreds of millions of years from now, many of our cities will indeed become fossils.

These fossil cities will be “a lot more robust than [fossils] of the dinosaurs,” geologists Jan Zalasiewicz and Kim Freedman wrote, and those fossils will consist of “the abandoned foundations, subways, roads, and pipelines of our ever more extensive urban stratum” – becoming “future trace fossils” of a lost form of life.

The already subterranean undersides of our modern cities, from Tube tunnels to secret government bunkers, “will be hard to obliterate. They will be altered, to be sure, and it is fascinating to speculate about what will happen to our very own addition to nature’s store of rocks and minerals, given a hundred million years, a little heat, some pressure (the weight of a kilometer or two of overlying sediment) and the catalytic, corrosive effect of the underground fluids in which all of these structures will be bathed.”

Plastics, for instance, “might behave like some of the long-chain organic molecules in fossil plant twigs and branches, or the collagen in the fossilized skeletons of some marine invertebrates.” A hundred thousand Evian bottles, then, might someday be transformed by compression into a new quartz: vast and subterranean veins of mineralized plastic.

Of course, all of this depends on the future tectonic fates of certain regions. Los Angeles, for instance, “is on an upward trajectory,” the geologists explain, “pushed by pressure from the adjacent San Andreas Fault system,” and so it is “doomed to be eroded away entirely.” But if a city is flooded, buried in sand, or otherwise absorbed downward, then “the stage is set to produce ideal pickling jars for cities. The urban strata of Amsterdam, New Orleans, Cairo and Venice could be buried wholesale – providing, that is, they can get over one more hurdle: the destructive power of the sea.”

[Images: Fossils, via the Fossil Museum].

[Images: Fossils, via the Fossil Museum].

Rather than talk about ruin value, then, which is so Romantically 18th century, why not strive for fossil value instead? Tens of millions of years in the future, when all of this urban infrastructure has turned to sludge, and radiative terrestrial heat has cooked old bricks into something resembling trace fossils, our cities could still be beautiful.

Can we design for this fate? Can we plan urban fossils ahead of time?

Can we give our constructions urban fossil value?

[Image: Antarctica by

[Image: Antarctica by  [Image: Istanbul Birds in Flight by

[Image: Istanbul Birds in Flight by  [Image: Bird subcommittee on traffic by

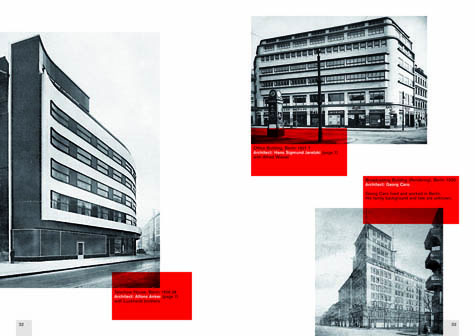

[Image: Bird subcommittee on traffic by  [Image: A spread from

[Image: A spread from

[Image: Spreads from

[Image: Spreads from  [Image: A spread from

[Image: A spread from  [Image: Tietz Department Store in Solingen (1930?), designed by

[Image: Tietz Department Store in Solingen (1930?), designed by

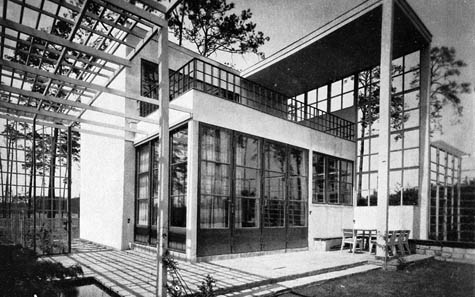

[Images: Showcase House, Werkbundsiedlung Breslow, by

[Images: Showcase House, Werkbundsiedlung Breslow, by

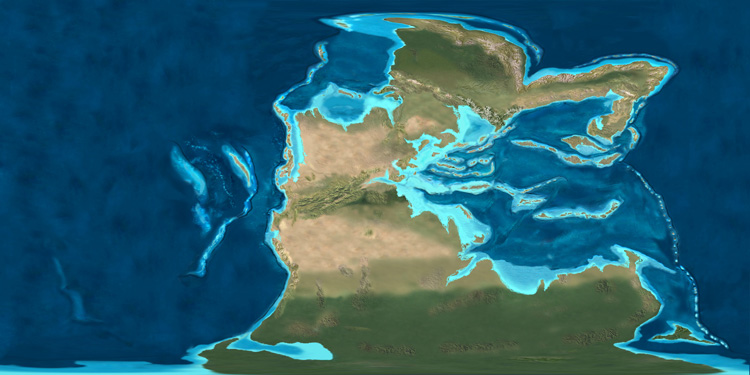

[Image: The earth 600 million years ago, in the late Precambrian Era; mapped by

[Image: The earth 600 million years ago, in the late Precambrian Era; mapped by

[Images: The tectonic paleo-history of the earth; mapped by

[Images: The tectonic paleo-history of the earth; mapped by

[Images: The tectonic paleo-history of the earth; in the last two images, you can see recognizable landmasses just beginning to form. Maps by

[Images: The tectonic paleo-history of the earth; in the last two images, you can see recognizable landmasses just beginning to form. Maps by

[Images: The earth from roughly 150 million years ago to 50 million years ago; mapped by

[Images: The earth from roughly 150 million years ago to 50 million years ago; mapped by  [Image: The earth in its present continental configuration; mapped by

[Image: The earth in its present continental configuration; mapped by  [Image: Three possible supercontinents, as mapped by

[Image: Three possible supercontinents, as mapped by  “The roots of garden pea plants were exposed to low-level electric current and subsequently produced 13 times more pisatin, an antifungal chemical, than plants that were not exposed to electricity,” we read. The specific experiment on which this claim is based involved applying “a 30 to 100 milliamp current to the growth-medium of plants grown hydroponically, or, in the case of

“The roots of garden pea plants were exposed to low-level electric current and subsequently produced 13 times more pisatin, an antifungal chemical, than plants that were not exposed to electricity,” we read. The specific experiment on which this claim is based involved applying “a 30 to 100 milliamp current to the growth-medium of plants grown hydroponically, or, in the case of  I’ve got a new post up on io9 this afternoon, and it might be of interest to readers here.

I’ve got a new post up on io9 this afternoon, and it might be of interest to readers here.  [Image: An illustration for Edgar Allan Poe’s

[Image: An illustration for Edgar Allan Poe’s  [Image: From a great series of photos called

[Image: From a great series of photos called  [Image: Via

[Image: Via  [Image:

[Image:  [Image: Via

[Image: Via  [Image:

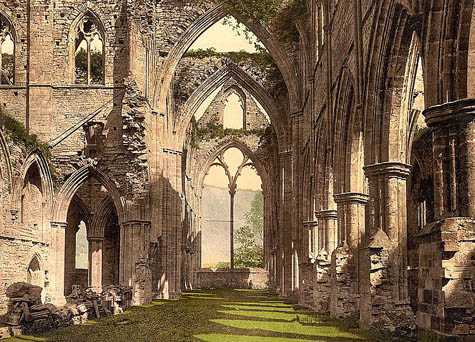

[Image:  [Image: Temple at Angkor, photographed by

[Image: Temple at Angkor, photographed by  [Image: Chemical weapons dumping sites in the Baltic Sea;

[Image: Chemical weapons dumping sites in the Baltic Sea;  [Image: Via the

[Image: Via the  [Image: The Farallon Islands, via

[Image: The Farallon Islands, via  [Image: Via the

[Image: Via the  And, whether or not anything of the sort ever happens, is there really any way to produce an accurate map of these and other dumping sites? Things shift; barrels move; information is lost; sand can cover everything. And even that assumes you’d get the funding you need to buy equipment – from side-scanning radar to air tanks and wet suits.

And, whether or not anything of the sort ever happens, is there really any way to produce an accurate map of these and other dumping sites? Things shift; barrels move; information is lost; sand can cover everything. And even that assumes you’d get the funding you need to buy equipment – from side-scanning radar to air tanks and wet suits.  [Image: From

[Image: From