I’m also pleased to announce that I’ll be on the jury for a design competition hosted in Chicago next month, brought to you by the Chicago Architectural Club. The purpose of the competition is to rethink – and redesign – Chicago’s Union Station, updating it for an era of high-speed rail travel in the United States.

I’m also pleased to announce that I’ll be on the jury for a design competition hosted in Chicago next month, brought to you by the Chicago Architectural Club. The purpose of the competition is to rethink – and redesign – Chicago’s Union Station, updating it for an era of high-speed rail travel in the United States.

Unfortunately, it’s a bit late in the game to be announcing this: designs are due by October 15!

But I’ve uploaded the competition brief to my Flickr page, so check it out �– and hopefully it’s not too late for some of you to participate.

I’ll be meeting with the jury to announce our decision on Sunday, November 9; you can read more about that here.

But if our transportation options change, and high-speed rail does become an infrastructural fact of American life, then how can the design of our cities keep pace? What will Chicago – indeed, what will all metropolitan forms in the American midwest – look like in the year 2020, if high-speed rail becomes a viable option? Will we see future super-cities hot-linked one to another across the plains – or simply well-made train stations plunked into existing cities here and there?

While I’m in Chicago next month I will also be hosting an amazing panel with Jeffrey Inaba, Sam Jacob, and Joseph Grima, easily three of the most interesting people working in architecture today – but I’ll be posting more about that soon.

Author: Geoff Manaugh

A mix of possible routes: BLDGBLOG speaks with Vito Acconci

A quick note before I hit the highway: I’ll be interviewing Vito Acconci on Saturday, live in Reno at the Nevada Museum of Art. This will be part of the Museum’s 2008 Art + Environment Conference, previously discussed here.

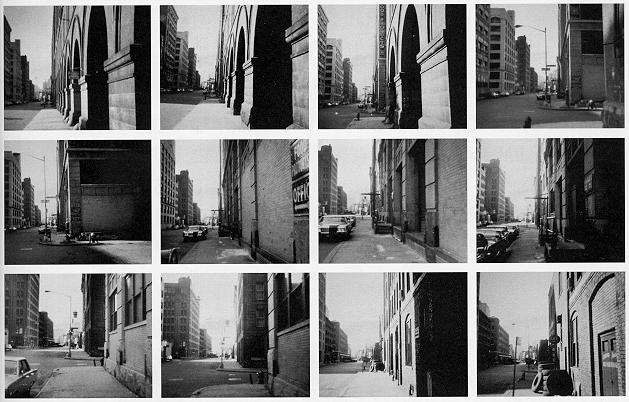

[Image: Vito Acconci, Blinks, Nov 23, 1969].

[Image: Vito Acconci, Blinks, Nov 23, 1969].

From an article about Acconci’s work in The New York Times:

”My biggest fear is that architecture is necessarily a kind of totalitarian activity, a kind of prison, in that when you design a space you’re probably designing people’s behavior in that space,” he says. ”So the goal of our work is to make a mix, a mix of possible routes, a mix of alternate routes, alternate channels.”

Be sure to read Shelley Jackson’s interview with Acconci in The Believer, take a look at his work courtesy of Azure, and stop by another profile of the artist-architect over at designboom.

[Image: An artificial island in Austria, designed by Vito Acconci].

[Image: An artificial island in Austria, designed by Vito Acconci].

I’ll report back with details next week (and hopefully with a transcript or recording of the event), and I hope to find the time to do some blogging from the event itself.

Of course, if you’re anywhere near Reno, please stop by!

[Image: Vito Acconci, from Following Piece, 1969].

[Image: Vito Acconci, from Following Piece, 1969].

(Note that the title for this post – “A mix of possible routes” – comes from the profile of Acconci written by Aric Chen for The New York Times).

Hitting the Books

I picked up a few books yesterday afternoon at a store in Pacific Heights, in the midst of assembling my “Further Reading” list for The BLDGBLOG Book, and so I’ve got books on the brain. I thought I’d take a minute or two to stroll through my bookshelves and call out a few of the titles I happen to be reading right now or have recently finished.

I picked up a few books yesterday afternoon at a store in Pacific Heights, in the midst of assembling my “Further Reading” list for The BLDGBLOG Book, and so I’ve got books on the brain. I thought I’d take a minute or two to stroll through my bookshelves and call out a few of the titles I happen to be reading right now or have recently finished.

So yesterday I bought Coal: A Human History by Barbara Freese. Coal tells “the fascinating history of a simple black rock that has shaped our world – and now threatens it.” Freese writes, and I quote at great length:

To grasp the magnitude of coal’s global impact, we must try to picture history without the momentous, high-intensity pulse of industrialization that started in Britain and then swept the world. The mainly agrarian world would have stayed in place for decades or centuries longer, with slower technological progress, less material wealth, and more gradual social change. Mass-production capitalism would not have soared to prominence, industrial working classes and places like nineteenth-century Manchester would not have mushroomed, and the Communist Manifesto would never have been written. The North might have lost the American Civil War, or it might never have started, and the transformation of the American West would have happened slowly by wagon rather than quickly by rail. The World Wars might never have exploded without the industrial rise of coal-rich Germany. Colonial conquests would have been far less sweeping, dramatically altering the history of all the societies that were dominated by foreign industrial powers, including China’s (whose ancient history would have been altered as well). The labor and environmental movements, if they had existed at all, would have taken very different forms. In short, none of the defining and epic struggles of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries would have played out as they did.

It’s the intrusion of geology into human history – a kind of economic batholith – the interaction between a fragment of the earth’s surface and the political development of the modern nation.

I also picked up a copy of The Slave Ship: A Human History – note the identical subtitles – by Marcus Rediker. Here, Rediker looks at the “floating dungeons” of the world’s earliest stab at transatlantic globalization:

For more than three centuries, slave ships carried millions of kidnapped Africans across the Atlantic in a “wooden world” where crew and captives alike lived with the ever-present fear of shipwreck, epidemics, and hungry sharks. As a cruel instrument of war and commerce, the slave ship helped to shape the Western world. Yet until now, it has remained a mystery.

Aside from being a social and economic history of the slave ship, the book also explores the ship’s technical structure – the mobile architecture of confinement.

I’ll hopefully start reading them both soon.

Books I’m currently in the process of reading, or have just finished, and that I’d recommend, include Kitty Hauser’s Bloody Old Britain: O.G.S. Crawford and the Archaeology of Modern Life. Crawford was an aerial archaeologist in England in the early 20th century, his “new skills of interpreting the earth from above,” discovering previously unknown landscape details, learned while flying reconnaissance missions during World War I.

Crawford and his colleagues, Hauser writes, “thought prehistory should be approached not through texts (as many archaeologists preferred) not through fetishized ‘finds’ (like those collected and admired by antiquarians), but through the spatial logic of geography. It made sense to think about the distribution of particular kinds of objects or sites over geographical space, rather than looking at them in isolation.” This was “a way of spatializing prehistory, restoring geographical connections and the materiality of the landscape to a subject that was too often reduced to disjointed objects or texts.” After all, she adds, “It was not just where ancient sites were to be found that interested him; it was how they related to each other, what constellations they formed, and how the siting of those constellations related to topography – geology, vegetation, trade routes, sources of water.”

[Images: O.G.S. Crawford and his aerially archaeological airplane; a view of the countryside from above, where remnants of history cast long shadows].

[Images: O.G.S. Crawford and his aerially archaeological airplane; a view of the countryside from above, where remnants of history cast long shadows].

Though I haven’t finished Hauser’s book yet, I’m enjoying it immensely. Hauser also sent me an essay called “Revenants in the Landscape: The Discoveries of Aerial Photography,” from her recent book Shadow Sites. On a casual skim here, that essay appears to deal with the trigonometry of shadows as seen from the air and what these shadows might indicate about unexplored – and abnormal – features in the English landscape. As she writes in Bloody Old Britain, “at certain times of day, when the sun is low in the sky, the outlines of ancient fields become visible over Salisbury Plain, as shadows throw their ridges and dimples into sharp relief; these are known as ‘shadow sites’.”

Speaking of Stonehenge, a few months ago I read Stonehenge, author Rosemary Hill’s excellent contribution to the Wonders of the World series edited by Mary Beard. While it might seem like the world can’t possibly need another book about Stonehenge, Hill’s approach is consistently interesting and deliberately written for a general audience. Throughout the book she describes the imaginative, political, artistic, and historiographic influence of the ancient monument, from William Blake’s engravings and the architecture of Inigo Jones to the Led Zeppelinized druidry of the late twentieth-century. I read a British copy of the book, published by Profile, but Harvard University Press – whose publicity blog is worth a read – has their own version coming out this fall.

For a monument of a different sort, we turn to Glen Canyon Dam. Just last week I finished reading James Lawrence Powell’s forthcoming book Dead Pool: Lake Powell, Global Warming, and the Future of Water in the West. I’d say more about that book here, in fact, but I’m reviewing it for another publication and so I’ll save my thoughts for that article. But it is an interesting book, if imperfect, and it presents some very large questions quite early on in the text.

Powell writes:

Why did our government dam nearly every river in the West, some a dozen times or more? Why were dams built even though the associated irrigation projects were obvious money-losers? Why, within a decade or two of the launching of the United States Reclamation Service in 1902, were every one of its founding principles betrayed?

More evocatively, he asks: “What do we do when across the West are spread not beautiful blue-water lakes, but a hundred million acre-feet of mud, some of it laced with toxins? Where then will our successors get their water?”

[Images: The cover of, and spreads from, Ant Farm: Living Archive 7 by Felicity D. Scott].

[Images: The cover of, and spreads from, Ant Farm: Living Archive 7 by Felicity D. Scott].

The idea of speculative futures for otherwise unanticipated monuments brings me to Felicity D. Scott’s recent book Ant Farm: Living Archive 7, published by ACTAR. Scott’s book is a graphically inspired but sluggishly written exploration of Ant Farm, a 1960s/70s American architectural avant-garde, whose projects included mobile educational facilities, “investigations into the psychedelic and environmental potentials of electronic technology,” inflatable parachute-buildings and “moment villages” in the American desert, and a bewildering variety of other experimental structures, almost all of which, Scott adds, were “portable, ‘instant,’ temporary, cheap, and high-tech.”

It’s Archigram-meets-NASCAR amidst inflatable polyethylene megastructures in the California desert – high on LSD and powered by cheap oil – prefiguring today’s ongoing experiments in rogue instant-urbanism, like Burning Man.

The book is beautifully designed and it includes an awe-inspiring 120-page Timeline of the group’s output; these images alone – really only about two-thirds of the book’s total eye candy – make it a rewarding and memorable resource.

I’ve been reading a load of other books lately, from Reza Negarestani’s future cult-classic Cyclonopedia to Robert MacFarlane’s outstanding The Wild Places, but I hope to post more about those titles soon.

Light Box

[Images: Object 02, including two interesting wire studies for the project, followed by a “light object,” all by Jeroen Molenaar – who also took this amazing photograph. Object 02 is on display now at the Cultuurwerkplaats R10 in Zwolle, Netherlands. The structure seems to visually exemplify the idea that a work of architecture could double as a cantilevered lighting fixture installed on its site in the city. Or what if small, inhabitable lamps dotted the urban field? You climb into your lamp at night – and turn it off to sleep. Residents who have gone to bed form a dark constellation of unlit structures against the illuminated backdrop of those who’ve stayed awake; the city becomes a burning signage that graphs sleep].

[Images: Object 02, including two interesting wire studies for the project, followed by a “light object,” all by Jeroen Molenaar – who also took this amazing photograph. Object 02 is on display now at the Cultuurwerkplaats R10 in Zwolle, Netherlands. The structure seems to visually exemplify the idea that a work of architecture could double as a cantilevered lighting fixture installed on its site in the city. Or what if small, inhabitable lamps dotted the urban field? You climb into your lamp at night – and turn it off to sleep. Residents who have gone to bed form a dark constellation of unlit structures against the illuminated backdrop of those who’ve stayed awake; the city becomes a burning signage that graphs sleep].

And the new White House is…

The White House Redux competition results have been announced!

The White House Redux competition results have been announced!

First Prize: #834

J.P. Maruszczak, Ryan Manning (assistant), Roger ConnahSecond Prize: #1485

David Iseri, Jefferson Frost, Justin Kruse, Laura SperryThird Prize (Shared):

#198

Grant Gibson, Chris-AnnMarie Spencer

#1369

Wayne Congar, Arrielle Assouline-LichtenHonorable Mention: #892

Pieterjan Ginckels, Julian Friedauer

Congratulations to all the winners – and a gigantic thanks to everyone who participated.

It was a lengthy, but very, very fun jury process, as partially documented in the video, below, and I have about half-a-million things I still want to add to the discussion, but I’ll wait until the popular vote is announced on October 3 before putting up a longer post.

[Image: The White House Redux jury meeting for a quick breakfast on the Die Hard-like unfinished 45th floor of World Trade Center 7 in New York; photo by Marty Hyers].

[Image: The White House Redux jury meeting for a quick breakfast on the Die Hard-like unfinished 45th floor of World Trade Center 7 in New York; photo by Marty Hyers].

Meanwhile, watch the jury deliberate at the end of the day (it was dark outside before we all left the building):

It’s interesting to watch this and the vox populi poll back to back:

More soon.

Into the Woods

A new exhibition called Forest, curated by Cécile Martin, opens up tomorrow night in Montreal. For the show, “artists and architects have joined forces to propose a new vision of the forest.”

There are three pavilions in all: “three installations that invite one to penetrate and explore the movements and dangers of the canopy, soil and hidden dangers of the forest.” They include the poetically named “From Chernobyl to Montreal, the Incandescent Zen Garden,” whose creators note that “the natural phenomena of radioactivity and sound waves are amplified,” with part of the installation “illuminated night and day by a red light, the same one that made the forest – the Red Forest – adjacent to the Chernobyl nuclear reactor vibrate.”

There are three pavilions in all: “three installations that invite one to penetrate and explore the movements and dangers of the canopy, soil and hidden dangers of the forest.” They include the poetically named “From Chernobyl to Montreal, the Incandescent Zen Garden,” whose creators note that “the natural phenomena of radioactivity and sound waves are amplified,” with part of the installation “illuminated night and day by a red light, the same one that made the forest – the Red Forest – adjacent to the Chernobyl nuclear reactor vibrate.”

This slightly unclear image nonetheless leaves me wondering what the biological effects might be if you could cause a several-acre test-forest to vibrate constantly: what strange roots and branches would grow? Would constant vibration cause radically new tree structures to grow – or just make for some very happy plants?

It’d be like the sound farm, only more tactile – and far stranger.

A perpetual earthquake as a lab for cultivating the unnatural.

The other two pavilions, meanwhile, are “The Macrocosm of Fiber or the Filtering Pavilion” and “The Mobile Branch, A Forest of Hypnosis and Vertigo.” The latter project, a collaboration between architect Philip Beesley – whose work was explored here a few years ago – and artist Patrick Beaulieu, is described a kind of animatronic thicket: “A raised three-dimensional flooring and a cover propelled at 300 rotations per minute form a vibrating dance of branches and twigs, constituting a human-sized space of the in-between from which humans are nevertheless excluded.”

You wander into a forest – only to realize that it’s not a forest at all, but a vast machine…

There are a series of workshops on Friday and Saturday, as well – so if you’re anywhere near Montreal, check it out! Tell them you heard about it on BLDGBLOG.

White House Redux: The Book

The White House Redux competition – discussed earlier this summer on National Public Radio – will soon be a book:

The White House Redux competition – discussed earlier this summer on National Public Radio – will soon be a book:

With almost 500 submissions from 42 countries around the world, White House Redux, a competition launched by Storefront for Art and Architecture and Control Group last January, became one of the most talked-about architecture competitions in 2008. The brief was simple: what would the residence of the most powerful individual in the world, the White House in Washington, D.C., look like if it were designed today?

Published to coincide with the opening of an exhibition of the competition’s results at Storefront for Art and Architecture, White House Redux—The Book contains a compendium of documentation related to the competition and an overview of the results. It includes essays by Joseph Grima (Storefront for Art and Architecture) and Geoff Manaugh (BLDGBLOG and Dwell Magazine), a history of the existing White House and 123 selected projects as well as the four winning submissions. A jury assessed the submissions in the spectacular setting of the 45th floor of the World Trade Center Tower 7, a process documented in the book’s 30-page photoessay by Marty Hyers.

The book is to be available for pre-order and will ship on October 2, 2008, to coincide with the prizegiving and opening of White House Redux at Storefront for Art and Architecture, New York. White House Redux was printed in a limited edition of 500 copies.

734 pages, color and black & white (7.8” x10.5”)

$39 USD Shipping: $5 (USA), $12 (Rest of the world)

Discounts available on shipping for multiple copies

With a print-run of only 500, the book should go fast – so order a copy before they all disappear.

(Note: This might be my last post here for a few days, as I’m going away for a quick – but much-needed – family vacation).

Outer Darkness

Apparently, “almost half” of the fluorescent light bulbs used in the Japanese module of the International Space Station have begun burning out far earlier than expected.

An entire section of the station thus might soon be left in darkness.

[Image: Kibo, the Japanese module of the International Space Station, soon to be without internal light].

[Image: Kibo, the Japanese module of the International Space Station, soon to be without internal light].

Although an impending delivery of new bulbs will undoubtedly bring light back to the failing module, the implication that astronauts aboard something like the International Space Station – or some special, trans-galaxial touring edition, launched twenty-five years from now – might be faced with total darkness, a darkness from which they cannot be rescued, is mind-boggling.

At the very least it would make a great film: ten minutes into what you think is a science fiction adventure story, all the lights on the ship go out. There is no way to replace the bulbs.

The next hour and a half you listen – after all, you can’t watch – as a group of orbiting athletes and scientists slowly comes to grips with their situation. They are drifting out past the rings of Saturn inside a strange constellation of unlit rooms – and they will never have light in the station again.

Five years from now one of them will still be alive, half-insane, speaking into a dead transmitter. The price of seeing stars is darkness, he whispers to himself over and over again, as his failing eyes gaze out upon nebulas and planets he’ll never reach.

(Via Wired Science).

The Landscape Anthropology of Photography Museums (and the spatial implications of graven images)

[Image: A new wing for the Museum of Photography in Charleroi by l’Escaut; photo by Filip Dujardin].

[Image: A new wing for the Museum of Photography in Charleroi by l’Escaut; photo by Filip Dujardin].

Belgian architects and scenographers l’Escaut have completed a new wing for the Museum of Photography in Charleroi, Belgium.

In an email received this morning, l’Escaut describes the project as being “situated at the intersection of architecture, landscape, city planning, photography and fine arts.”

This wide-ranging program, they go on to point out, “matches the interdisciplinarity of l’Escaut both in its daily life (l’Escaut is situated in a building shared with theatre actors and artists) as in its architecture practice (anthropology, landscaping, city planning, communication intervene in the projects).”

They are not really architects, in other words; they practice something more like landscape anthropology.

[Images: A new wing for the Museum of Photography in Charleroi by l’Escaut; photos by Filip Dujardin].

[Images: A new wing for the Museum of Photography in Charleroi by l’Escaut; photos by Filip Dujardin].

L’Escaut’s new wing is a surprising addition to the existing structure.

Partly raised on stilts, partly cantilevered, and almost entirely defined by a very clean-lined modern geometry, the added galleries nonetheless include a brief glimpse of botanical free-will: a “winter garden” that “shelters fragrant plants inside the museum.” Photosynthesis meets photography.

[Image: A new wing for the Museum of Photography in Charleroi by l’Escaut; photo by Filip Dujardin].

[Image: A new wing for the Museum of Photography in Charleroi by l’Escaut; photo by Filip Dujardin].

The galleries themselves, we’re told, are part of an overall “spatial scenography” of the site. Everything here is about views, counter-views, cross-views, and panoramas. Everything helps to frame everything else.

The architecture itself is photographic, you could say: the rooms flow into each other through a succession of bare white walls and exposed concrete, as if the space has been edited.

This raises the question, though, of the point at which space, actively experienced, becomes cinematic.

Are buildings ever truly photographic, or are they more like short films?

[Images: A new wing for the Museum of Photography in Charleroi by l’Escaut; photos by Filip Dujardin].

[Images: A new wing for the Museum of Photography in Charleroi by l’Escaut; photos by Filip Dujardin].

In any case, the story behind the original building itself is fascinating: it turns out that the Museum of Photography is a former Carmelite convent. The grounds include what used to be the nuns’ orchard.

This entails all sorts of interesting theological problems, as we’ll see.

[Image: A new wing for the Museum of Photography in Charleroi by l’Escaut; photo by Filip Dujardin].

[Image: A new wing for the Museum of Photography in Charleroi by l’Escaut; photo by Filip Dujardin].

Religious prohibitions against “graven images” become abstractly involved in the planning process:

The transformation of the convent into a museum of photography was a reverse process of existing logics in the building. A place where looking at the world was forbidden because of religious reasons became a place of revelation of the image for societal reasons. Its extension defies conventional museum logics by multiplying the relationships to photography, its history and its many facets of representation.

In other words, is a museum of photography – a temple of the graven image – a site for the “revelation of the image,” as the architects write – an inherent violation of Christian doctrine?

Is it de facto heresy to celebrate photography in a site formerly dedicated to the worship of god?

These unresolved tensions help to animate the interlinked spaces of the museum itself.

[Image: A new wing for the Museum of Photography in Charleroi by l’Escaut; photo by Filip Dujardin].

[Image: A new wing for the Museum of Photography in Charleroi by l’Escaut; photo by Filip Dujardin].

Here are some photos of the construction process, More about the project, meanwhile, can be found here.

Artificial Migration Routes for Monarch Butterflies

Something about the previous post reminded me of a project by Elliott Malkin called Graffiti For Butterflies.

[Images: Graffiti For Butterflies by Elliott Malkin].

[Images: Graffiti For Butterflies by Elliott Malkin].

Graffiti For Butterflies attempts to “direct” monarch butterflies “along migratory routes in North America,” using “images of milkweed flowers to broadcast the location of food sources.”

Malkin applies sunblock to these images in order “to optimize the graffiti for butterfly vision.” He calls this Urban Interspecies Communication.

Overlooking the most basic question here – of whether or not this would actually work – the very idea that we might deliberately construct an alternative visual system inside our cities, legible only to other species, is totally fascinating. What devices of route-finding and navigation could we purposefully produce for non-humans?

Is there a burgeoning field of graphic design for other species? Post-human signage and symbology?

There are already olfactory labyrinths left behind by dogs, for instance, and there are accidental but extraordinarily complex sense-trails following us everywhere – from food scraps to automobile exhaust to whiffs of perfume on the subway – but what deliberate “graffiti,” otherwise undetectable by humans, could we create in order to help other species navigate the urban world?

Using special UV paints to mark artificial migration routes across the continent seems like an amazing way to begin the investigation.

The Brain in Space (Cognition and the City)

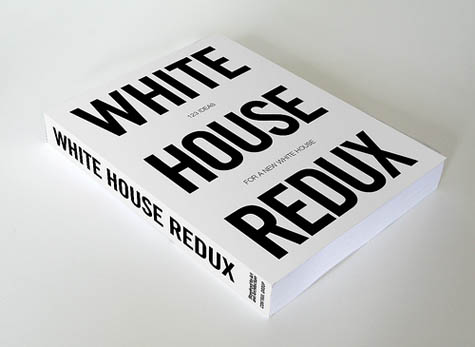

[Image: Route-finding and spatial perception in the brain; via the BBC].

[Image: Route-finding and spatial perception in the brain; via the BBC].

Like something out of a short story by China Miéville, “scientists have uncovered evidence for an inbuilt ‘sat-nav’ system in the brains of London taxi drivers,” the BBC reports. “They used magnetic scanners to explore the brain activity of taxi drivers as they navigated their way through a virtual simulation of London’s streets. Different brain regions were activated as they considered route options, spotted familiar landmarks or thought about their customers.”

Taxi cab drivers’ brains, we read, “even ‘grow on the job’ as they build up detailed information needed to find their way around London’s labyrinth of streets – information famously referred to as ‘The Knowledge’.”

It’s interesting to note, meanwhile, that this appears to be an almost complete retread of news released more than eight years ago. There we learn not only that “the hippocampus is at the front of the brain,” but that it “was examined in Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) scans on 16 London cabbies.”

Cabbies’ brains, that article reports, “‘grow’ on the job.”

However, it’s also interesting to speculate here that “sat-nav” was not referred to by that earlier article because certain technologies – such as dashboard navigation and handheld GPS – simply had not yet reached an adequate price-point, or the required level of social acceptance, for “sat-nav” to be useful to that writer as a metaphor.

If this were true, then perhaps you could track the infiltration of GPS and sat-nav technologies into the fabric of everyday life by the speed with which they have become recognizable as urban-spatial metaphors.

(Via Boing Boing and Geoffrey S. George).