[Image: Outside the Tesla factory; Instagram by BLDGBLOG].

[Image: Outside the Tesla factory; Instagram by BLDGBLOG].

The coolest thing about a tour of the Tesla factory out in Fremont, California, is the huge metal-stamping machine—a behemoth piece of equipment that applies more than five thousand tons of pressure in order to mold metal parts in an instant. In fact, it was not even the company’s largest stamping machine, which was offline the afternoon I went through.

You hear this thing long before you see it: a thundering and resonant split-second blast that sounds more like a minor-key chord being sledgehammered out into the cavernous factory. Then the machine cycle repeats itself: parts are removed, dragged, and rattled into place, followed by the preliminary crash of a new metal sheet being lowered into the bay. Then bam, that weird sound again, equal parts dark ambient soundscape and sci-fi howl.

Strangely, though, there is an air of melancholy to the sound—a kind of unexpected pathos—as if the machine had accidentally been tuned to some minor and wistful harmonic. The instantaneous hydraulic detonation of what sounds like an organ chord thus rings out, augmented by the foot-shuddering bass of the stamp itself, which sends small earthquakes rolling through the floor. (In fact, this reminded me that the factory is more or less directly above the Hayward Fault and I began to wonder what seismic effects such a colossal machine might actually be having.)

The machine only got louder and louder as we wound our way through a complicated back-turning maze of welding walls and robot arms. Finally visible, it seemed to be made entirely of gates: a giant red portal through which shaped metal could pass.

[Image: The red gates of metal-stamping machine; photo courtesy of Tesla].

[Image: The red gates of metal-stamping machine; photo courtesy of Tesla].

As we stopped to watch, the slow rhythm of its sounds matched up with processional movements now visible deep inside the cathedral-sized device, and the overall process began to make more sense.

Two men in full ear protection stood there, silhouetted against the mouth of the machine, presumably hypnotized by its otherworldly, repetitive soundtrack—or maybe that was just me, perhaps overly willing to hear, in the looped noise of this exotic machine, music that wasn’t really there.

In any case, I was on the tour as part of a workshop run last week at the UC Berkeley College of Environmental Design, with students from Nicholas de Monchaux‘s course at Berkeley and a small group visiting from Smout Allen‘s & Kyle Buchanan‘s Unit 11 over at the Bartlett School of Architecture in London.

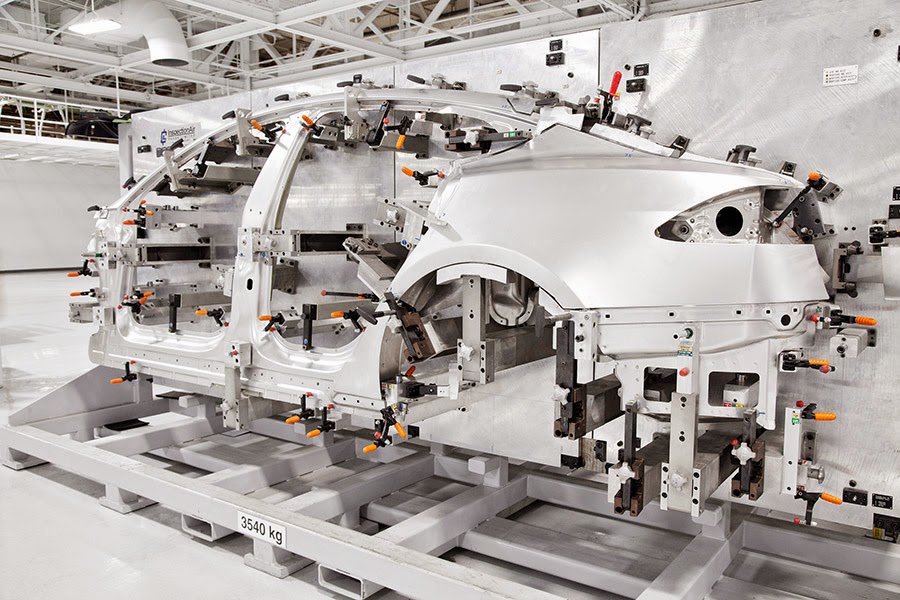

[Image: Photo courtesy of Tesla].

[Image: Photo courtesy of Tesla].

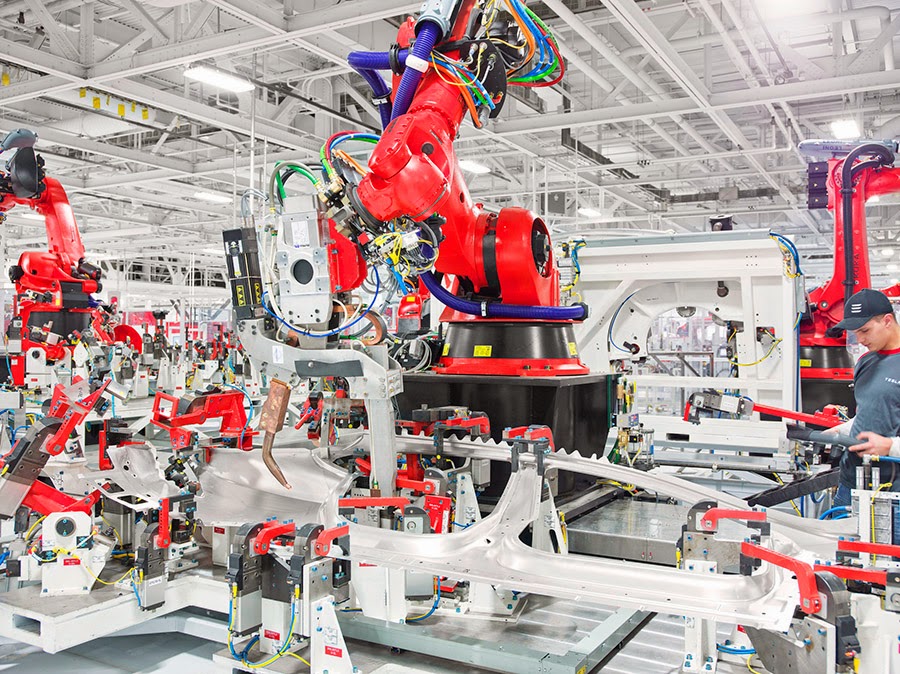

The idea behind the tour was not only to see robots at work but to experience the spatial logic of a factory, its interior the size of 80 football fields broken down into sequential functions and clusters, with color-coded circulation diagrams painted directly onto the concrete floor.

At least those were the paths meant for humans. For self-driving robots, long curving whirls of magnetic tape had been applied to the floor, forming cursive, counter-directional arabesques that only made sense when you considered the aggressive turning radii of those bulky machines.

It was the robot-readable world firsthand, or an indoor landscape architecture for machines.

There is a strict no-photo policy in place, unfortunately, and you are obliged to sign a non-disclosure agreement prior to entering the facility, so the only interior photos I have to show are from Wikipedia and Tesla’s own press page.

[Image: Photo by Steve Jurvetson, via Wikipedia].

[Image: Photo by Steve Jurvetson, via Wikipedia].

The actual tour is very much in the vein of a corporate sales pitch, and it is delivered with true American gusto (and at very high volume), but it’s worth taking. Technically, by entering the factory you step into a foreign free-trade zone, which, for anyone else reading Keller Easterling’s new book, is an interesting thing to do in person, like entering a corporate eruv.

Once inside, you see things like aluminum rapid-injection molds, laser-cutting stations, and emergency “light curtains” dividing humans from the machines they steward. You see “laser-calibration trees,” or knobby poles branching with small geometric ornaments; they are used by laser-scanners for re-booting themselves after measuring the frames of new cars.

At the very end of the process, you see massive, Japanese-made robots lifting entire finished Teslas overhead as if they’re feathers. Each machine has been named by Elon Musk after X-Men characters: there is Thunderbird and Cyclops, Storm and Colossus, Xavier, Changeling, Ice Man, Wolverine, and Angel.

[Image: Photo courtesy of Tesla].

[Image: Photo courtesy of Tesla].

And, perhaps best of all, you might be lucky enough to see engineers training new robots for eventual roles in the assembly process.

Our tram slowed down for just a few seconds so we could watch a woman, less than two-thirds the size of the mechanical arm lurching back and forth in front of her, patiently coding new movements into the gyroscopes and actuators inside the machine.

Uncertain of what we were seeing, we tried to make sense of the drunken movements on display, which looked more like a snake hypnotized by its master, swaying side to side like a cobra being woken up from a dream.

At one point, our tour guide gestured out at literally dozens—perhaps hundreds—of new robots still under plastic wrap, all awaiting training and installation. The factory is expanding dramatically as Tesla gears up for the release of their new SUV.

We have “an army of robots under plastic,” the guide said enthusiastically, and he laughed. If there’s ever a robot uprising, he joked, this is probably not the best place to be.

[Image: Photo courtesy of Tesla].

[Image: Photo courtesy of Tesla].

It seems that our group’s educational affiliation made getting a tour much easier, but you can try your own luck using Tesla’s Contact page.

Great article, well written, can't wait to see it for myself!