[Image: Screen-grab from The New York Times].

[Image: Screen-grab from The New York Times].

Peruvian archaeologist Luis Jaime Castillo Butters “has created a drone air force to map, monitor and safeguard his country’s ancient treasures,” according to the New York Times.

Researchers in Peru “struggle to protect the country’s archaeological heritage from squatters and land traffickers, who often secure property through fraud or political connections to profit from rising land values,” we read. “Experts say hundreds, perhaps thousands of ancient sites are endangered by such encroachment.”

What’s needed, it seems, is a kind of standing army or reserve corps of mechanical eyes, ready to take flight at a moment’s notice and document abuses or vandalism at historic sites, and this, the article implies, is at least one of the ultimate goals. Indeed, “drones can address the problem, quickly and cheaply, by providing bird’s-eye views of ruins that can be converted into 3-D images and highly detailed maps.”

At least that’s the goal. Actually watching the “drone air force” at work, however, doesn’t quite live up to rhetorical expectations. Instead, sand grains cause mechanical failure, batteries need to be checked and replaced, the geometrically skewed images coming back from the camera are difficult to reconcile with one another, and the small team of archaeological operators only manages to perform a short flight over the targeted valley before calling their DJI Phantom back to base.

Having said that, though, aerial landscape data culled not just from UAVs but from cameras and scanning equipment carried by kites, helium balloons, satellites, light aircraft, and even helicopter patrols has had a transformative effect on archaeological fieldwork.

[Image: A glimpse of the balloon rig, from Mozas-Calvache et al., Journal of Archaeological Science].

[Image: A glimpse of the balloon rig, from Mozas-Calvache et al., Journal of Archaeological Science].

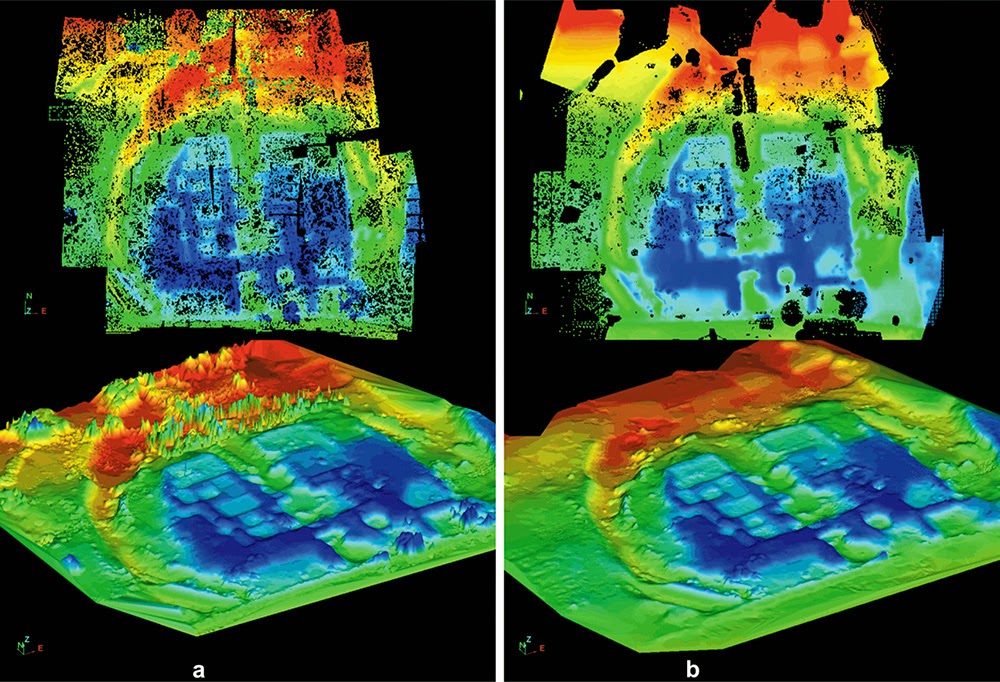

Just one example of this—and there are literally hundreds, as any search through publications such as the Journal of Archaeological Science or World Archaeology will reveal—was an exploration of how the images produced by balloon-based “light aerial platforms” could be made more useful.

Of course, the possible uses for this technique in contemporary architectural or urban documentation and analysis should not be overlooked.

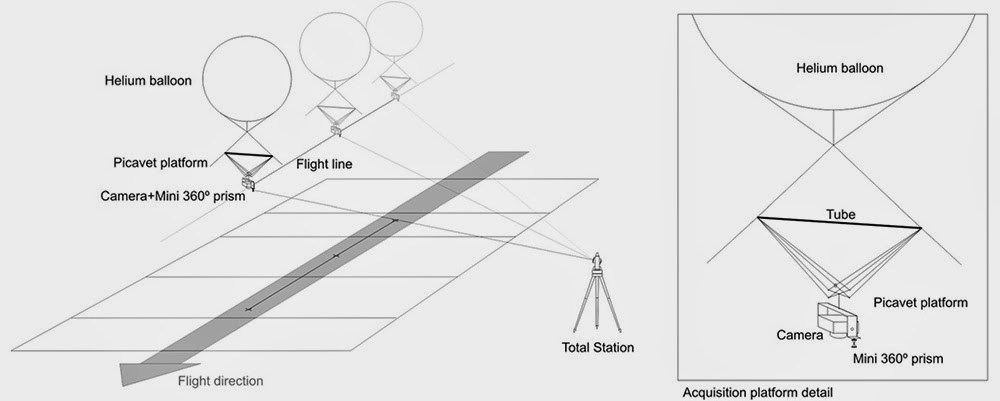

[Image: The balloon rig diagrammed, from Mozas-Calvache et al., Journal of Archaeological Science].

[Image: The balloon rig diagrammed, from Mozas-Calvache et al., Journal of Archaeological Science].

As authors A.T. Mozas-Calvache et al., from the University of Jaen in Spain, explain in a paper for the Journal of Archaeological Science, they have developed “a complete methodology for performing photogrammetric surveying of archaeological sites using light aerial platforms or unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) systems. Traditionally, the main problem with using these platforms is the irregular geometry of the photographs obtained.”

This can make combining the resulting images into a comprehensible map or visual survey fantastically time-consuming, if not sometimes impossible; by comparison, think of a badly stitched panorama on your smartphone, now multiple that times a hundred and you can imagine some of the difficulty involved.

Instead, Mozas-Calvache and Co. built a helium-balloon-based “light aerial platform” whose “spatial coordinates are incorporated in the memory card of a robotized total station for automatic tracking of a 360 º mini reflector prism installed in the camera platform”—all of which is just a more precise way of saying that the location of the camera or scanner is precisely known at every step of its passage over the site, and the resulting, well-gridded images can thus be more easily reconciled.

[Image: Some resulting images, from Mozas-Calvache et al., Journal of Archaeological Science].

[Image: Some resulting images, from Mozas-Calvache et al., Journal of Archaeological Science].

But now we’re getting off-topic. For more about the “drone air force” of Peru, check out The New York Times.